The Locations of the Music Life in Pest-Buda

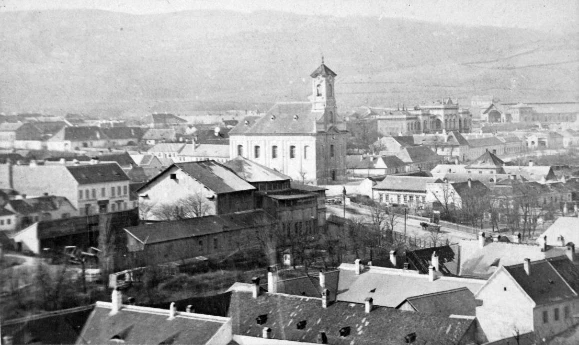

German-language Musical Theatre in Pest

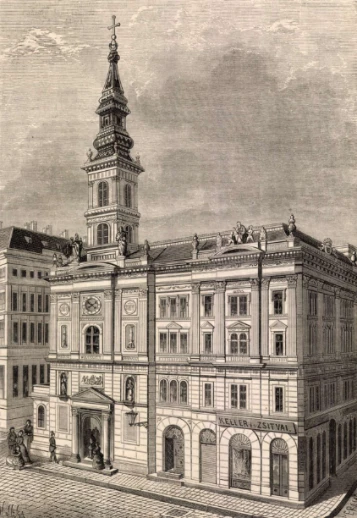

The German Municipal Theatre of Pest opened on 9 February 1812, with a grand ceremony. For the opening, August von Kotzebue wrote an occasional play, and Beethoven composed the incidental music. The neoclassical building could accommodate approximately 3,500 spectators. Although it primarily hosted German-language performances, Hungarian artists also appeared on stage, including Róza Déryné Széppataki and Ferenc Erkel. In 1847, the theatre was destroyed by a fire.

The German Theatre on Wollgasse [lit. Wool Street] operated from 1869 to 1889 at what is now 24 Báthory Street. The auditorium, accessible from the foyer, was 32 meters long and 21 meters wide at its broadestst; it could accommodate between 1,500 and 2,000 spectators. The opening performance was Johann Strauss Jr.’s operetta Die blaue Donau. The theatre hosted significant German guest performers and played an important role in the era of German-language theatre in Hungary. This building, too, was destroyed by fire in 1889.

This 1845 lithograph by Rudolf Alt depicts the Royal Municipal Theatre (Königlich Städtisches Theater in Pesth), which opened its doors in 1812.

Collection of the Hungarian National Museum.

Hungarian-language Musical Theatre in Pest

The Castle Theatre in Buda opened on 17 October 1787, as the city’s first permanent theatre. After the 1833 split of a traveling company that primarily performed in Kolozsvár (Cluj) and Kassa (Košice), part of the troupe, led by Elek Pály, moved to Buda. At that time, the company included ten musicians, and by the following year, the number had grown to fourteen. However, due to the lack of a qualified conductor and skilled singers, they performed mostly lighter musical plays. In 1834, new singer-actors were hired, but the real breakthrough came in 1835: on April 11, Rossini’s The Barber of Seville was staged, conducted by Ferenc Erkel. From May to November, Róza Széppataki Déryné also appeared in guest performances in Buda, and her presence gave a strong boost to opera productions. However, during the winter months, financial difficulties arose. After the end of her engagement, Déryné left the company, and Erkel, too, accepted a position as assistant conductor at the German Theatre in Pest.

Hand-colored period print of the Castle Theatre in Buda, based on a drawing by Ignác Weissenberg

MNMKK National Széchényi Library, Theatre History Collection

National Theatre

The opening of the Hungarian Theatre of Pest in 1837 was a significant step toward a permanent institution. In 1840, the theatre—previously operated by the county of Pest—came under national patronage. From the premiere of Ferenc Erkel’s first opera Bátori Mária on 8 August 1840, the institution bore the name National Theatre. In the 19th century, both spoken drama and opera performances took place under the same roof. During the 1840s, the number of opera performances increased, accompanied by a growing permanent orchestra. By 1853, the National Theatre orchestra numbered 46 musicians, while the newly founded Philharmonic Society had 47 members. Until the opening of the Hungarian Royal Opera House in 1884, the National Theatre was the most important venue for Hungarian-language opera in Pest-Buda.

Colored aquatint engraving by Frederic Martens after a drawing by Josef Kuwasseg

MNMKK National Széchényi Library, Theatre History Collection

Opera House

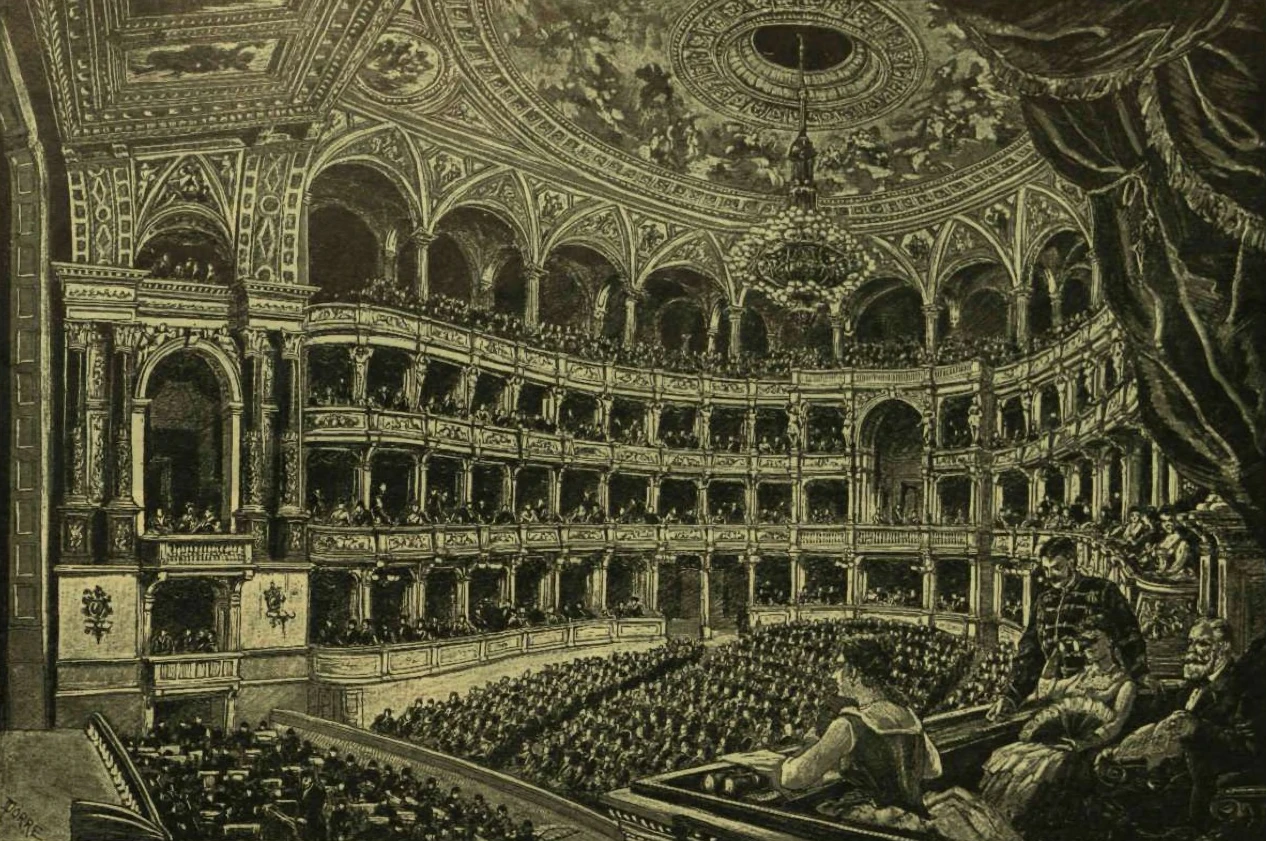

The Royal Hungarian Opera House opened its doors on Andrássy Avenue on 27 September 1884, and has since remained Hungary’s most prominent institutions for opera and ballet. By the end of the 19th century, it had become clear that a dedicated opera house was needed, as the National Theatre could no longer adequately host both drama and opera performances. Architect Miklós Ybl won the design competition and made every effort to ensure the building was constructed by Hungarian craftsmen using local materials. Although Emperor Franz Joseph stipulated that the opera house in Pest should not be larger than the one in Vienna, Ybl refined the proportions to create an aesthetically outstanding building. At the grand opening—attended by the Emperor himself—excerpts from Bánk Bán, Hunyadi László, and Lohengrin were performed under the direction of Ferenc Erkel and his son Sándor Erkel.

Illustration from the Vasárnapi Ujság [Sunday Times], published in the issue of September 26, 1909.

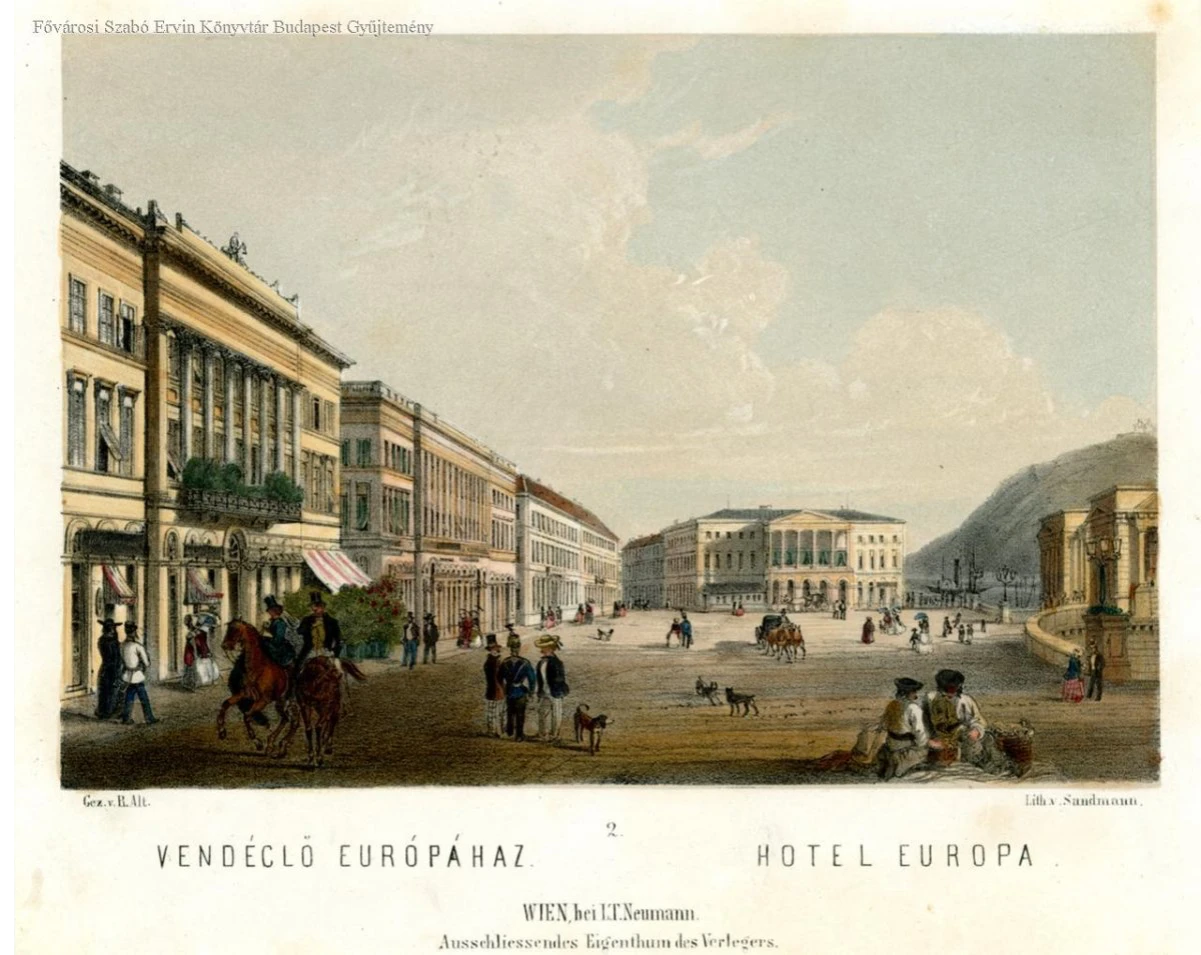

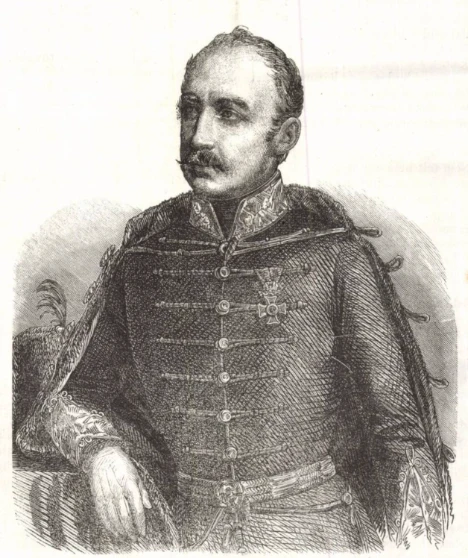

Lloyd palace

Between 1826 and 1830, the Lloyd Company's Pest-Buda building was constructed near the Pest end of the Chain Bridge, based on designs by József Hild. The building was home to the National Casino, which was founded by István Széchenyi, as well as a restaurant where musicians would perform. The Pest Lloyd Trade Company's headquarters were located there from 1851, and the palace also served as the editorial office for the Pester Lloyd magazine. Various events, concerts and balls were held in its ceremonial hall. Recent research has revealed more information about these elegant concerts, which were held regularly and included charity concerts. Performers included Clara Schumann, Franz Liszt, Rozália Schodel, Henri Vieuxtemps and József Joachim.

![Klösz György: 75. Régi tőzsde épület / Altes Lyodgebäude [!] [1867–1877]. Photograph](/images/loc-5.webp)

FSZEK Budapest-képarchívum

New Venues Appearing at the Middle of the Century

Chamber music, solo, and/or mixed concerts were held, apart from the Lloyd Palace, in the large halls of hospitality companies, such as the Inn to the Seven Prince Electors, the Hotel Hungaria, or the Hotel Europe. During the mid-19th century, Imre Székely as well as the string quartets led by Dávid Ridley-Kohne and Adolf Spiller gave several concerts at Hotel Europe. In the second half of the century, in addition to the Redoute, new types of music venues appeared. One of these was salon of piano maker Beregszászy, which, in addition to serving as a showroom, also hosted chamber music concerts.

FSZEK Budapest-képarchívum

Concert Venues in the Last Third of the Century

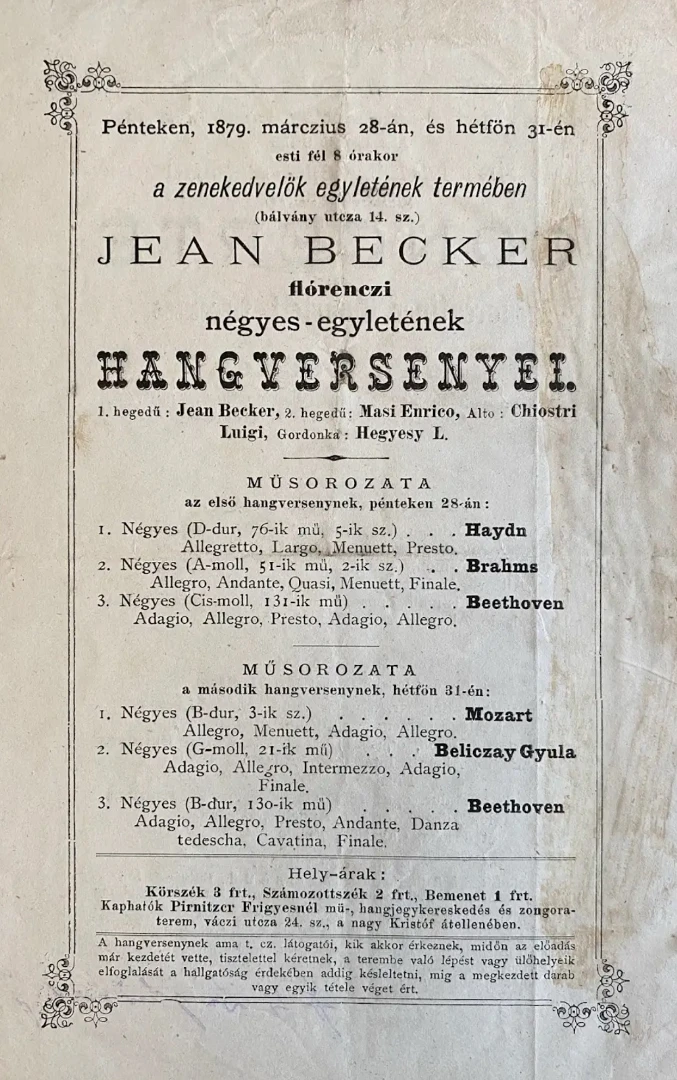

The hall of the Music Lovers’ Association saw the appearance of Johannes Brahms, among others, and hosted the performances of two world-famous ensembles: the Viennese String Quartet led by Joseph Hellmesberger and Jean Becker’s Florentine String Quartet. The audience, however, did not like the hall. They criticized not only the acoustics but also the single narrow exit of the building, which took minutes to pass through after the concert.

HUN-REN BTK Zenetudományi Intézet

Ferenc Liszt held his Sunday morning performances from the end of 1870 at the Inner City Parish Church of Pest. The first matinée was attended by fifty guests, the second by one hundred. The number of attendees at the third concert rose to an astonishing number.

The Royal Grand Hotel was completed for the millennial celebrations (1896). With 350 rooms, the Royal was the largest hotel in Europe at the time. In its great hall, world stars such as Jenő Hubay, Béla Bartók, Ernő Dohnányi, Moriz Rosenthal, József Joachim, and Emil Sauer performed.

Ball and concert in Pesti Redoute and Pesti Vigadó

The Redoute (later Pesti Vigadó) was an important venue in the 19th century Pest-Buda. Many internationally renowned musicians performed there, including Johann Strauss Jr., as well as Hungarian composers Ferenc Erkel and Ferenc Liszt. The building was inaugurated in January 1833 with a ball. As well as balls, concerts were regularly held in the building, which also housed Johann Pachl's musical instrument shop and a catering facility. The Pest-Buda Choir also used the Redout for rehearsals at that time. The building was significantly damaged during the 1848–49 Revolution. Following reconstruction, the renamed Vigadó hosted the premiere of Liszt's 'Legend of Saint Elizabeth' in 1865 and was visited by Mascagni, Dvořák, Debussy and Artur Rubinstein. Ernő Dohnányi also gave his first solo concert here.

![The new redout room at the Pesti Vigadó in Pest, during the People's Ball. K[ároly] Rusz. [1865]. Graphic.](/images/loc-9.webp)

FSZEK Budapest-képarchívum

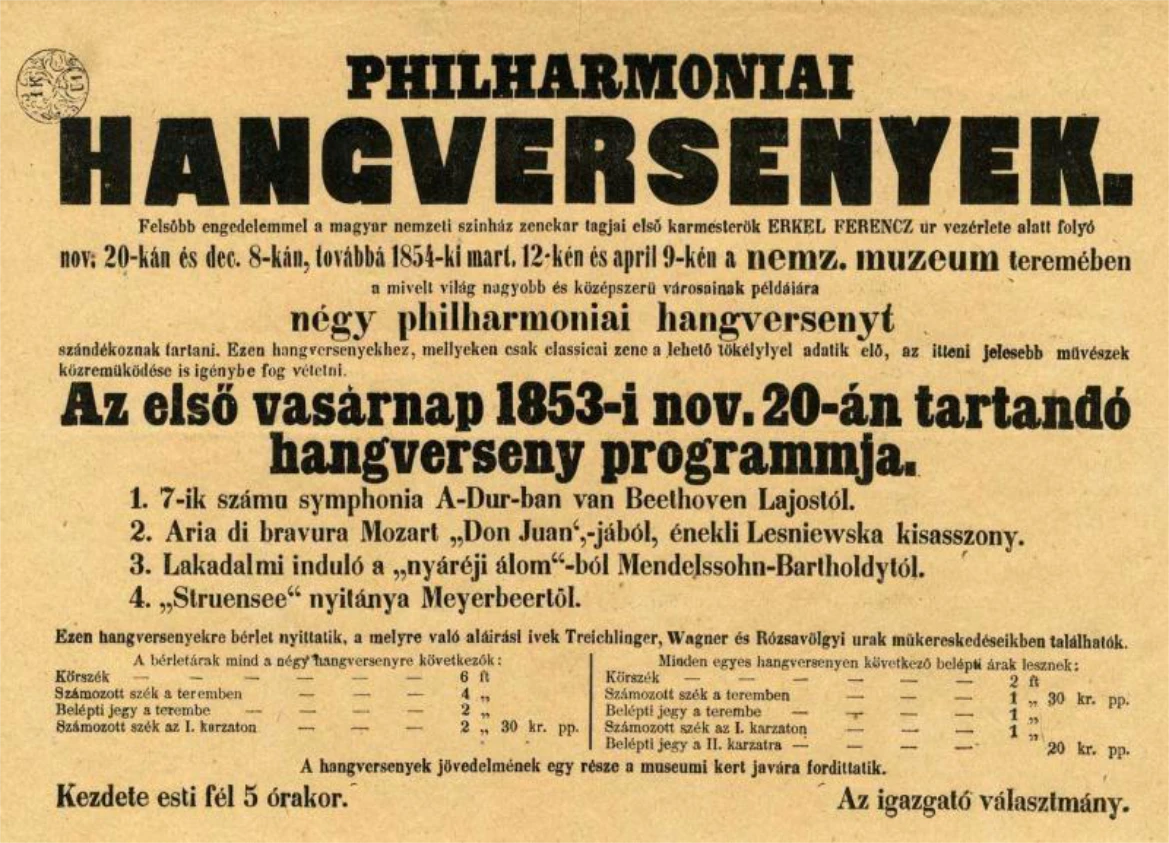

Philharmonic Society Orchestra

Founded in 1853 and still active today, the Philharmonic Society Orchestra was the first professional symphonic ensemble in Hungary. The ensemble emerged from the orchestra of the National Theatre: while the theatre’s ensemble numbered 46 musicians at the time, the newly established society counted 47 members. Their goal was to fill the gap in the capital’s musical life caused by the absence of regular, high-quality symphonic concerts. The foundation of the orchestra—or at least the first significant step leading to it—is credited not only to Ferenc Erkel but also to the Doppler brothers, Ferenc and Károly, both musicians of the National Theatre in Pest. In the summer of 1853, upon returning from their concert tour abroad, they submitted a petition to the director of the National Museum, requesting the use of the museum’s ceremonial hall for several philharmonic concerts. Their aim was to ensure that Pest would not lag behind other cultured cities, either in Hungary or abroad, in terms of artistic achievement.

Music societies: the first serious initiative in Pest

The first singing schools in Pest were initiated by the first musical societies of Pest-Buda: Vidámság Társulata [Merriment Society], active between 1834 and 1836, and Pest-Budai Hangászegyesület [Society of Pest-Buda Musicians], growing out from the previous one in 1836 with the support of Royal Councilor Lajos Schedius, following the model of similar Viennese institutions. From 1840 onward, under the leadership of Gábor Mátray—the pioneer of Hungarian musicology and research in domestic music history who also organized the first historical concerts in Hungary—the Society continued to operate under the name Hangászegyleti Zenede [Conservatory of the Musicians’ Society]. Later, the curriculum was enlarged to include instrumental training—primarily in piano, violin, and cello playing—as well as instruction in poetry reading. In 1867, the institution adopted the name Nemzeti Zenede [National Conservatory]. However, without permanent headquarters, it operated in rented tenement buildings and apartments. It was not until 1897 that the Conservatory was able to move into its new residence located in today’s Semmelweis utca, back then known as Újvilág utca [New World Street].

National Széchényi Library, Digital Image Archives

Music societies: an initiative in Buda

In 1867, i.e. the year of the Austro-Hungarian Compromise, two additional musical institutions were established. On the Buda side, Budai Ének- és Zeneakadémia [Buda Academy of Singing and Music] was founded in 1866 as the “secular branch” of Budai Egyházi Zeneegyesület [Buda Church Music Society]. On the Pest side, Budapesti Zenekedvelők Egyesülete [Society of Budapest’s Music Lovers] came into being, also offering musical instruction, mainly on elementary level, from 1885. Apart from professional music institutions, only these two societies had the proper ensembles able to perform large-scale oratorios in Budapest. During the last third of the nineteenth century, many baroque and classical works received their first performances in Pest under their auspices. Organist and composer Zsigmond Szautner, who led the Buda Academy, and conductor Imre Bellovics, who directed the Pest society for several decades, were both key figures of this period who shaped the sacred and secular musical life of the city.

![The Capuchin Church of Buda, a.k.a. the Church of Saint Elizabeth of Lower Watertown (located at 32 Fő utca [lit. Main Street] of Budapest’s District 1) – The residence of the Buda Academy of Choir and Music.](/images/loc-12.webp)

HUN-REN RCH Institute for Musicology

Academy of Music

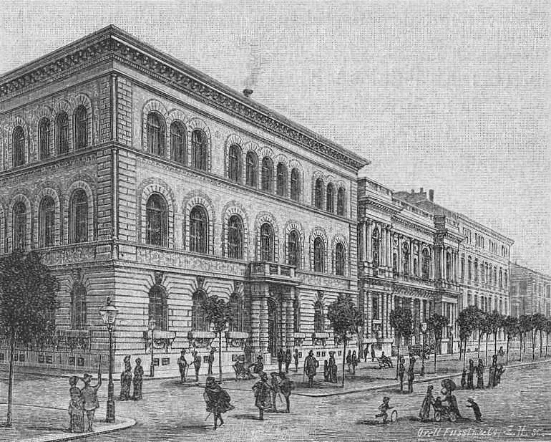

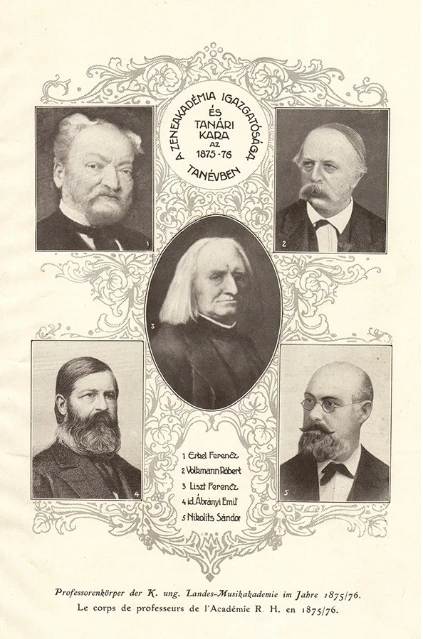

The institutionalized higher education in the musical arts began in the Hungarian capital in 1875, with the founding of the Academy of Music. Initially housed in a rented building on Hal tér [lit. “Fish Square”], also accommodating Ferenc Liszt’s residence, the Academy was established with the support and presidency of Liszt himself, as well as the directorship of Ferenc Erkel. At the outset, education was limited to the piano playing and/or composition training of a mere 38 students. Alongside Liszt and Erkel, the first faculty included Robert Volkmann, Kornél Ábrányi Sr., and Sándor Nikolits. In 1879, the Academy was given in a new building on Sugár út [lit. “Radial Road,” a proper name, which later became common noun in Hungarian—sugárút—, lit. “avenue” or “boulevard,” roughly around the same time when the Road was re-named Andrássy út, which is the current name of this pivotal urbanistic artery]. This re-location also allowed for the launch of additional departments. With the appointment of Hans / János Koessler in 1882, training in organ and choral conducting, shortly thereafter—under the leadership of Richárd Pauli and Adél Passy-Cornet—solo singing became a discipline of the Academy. From 1886, Jenő Hubay led the Violin Department and David Popper led the Cello Department. The international reputation of the entire staff began to attract an increasing number of students. The Academy’s today main building was completed in 1907, at a time when student enrollment had surpassed 500.

![The first building of the Academy of Music, located at 4 Hal tér [lit. Fish Square].](/images/loc-14.webp)

Fortepan / Budapest City Archives, photo by György Klösz.

Széchényi Library, Digital Image Archives

National Széchényi Library, Digital Image Archives

Ferenc Liszt Memorial Museum and Research Centre.

The Coronation Church of Buda: The Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary (Matthias Church)

In the 19th century, the vibrant cultural scene of the Castle District saw numerous prominent figures of Hungarian music life as well. It is hardly a surprise that Ferenc Erkel resided in here with his family, as his father-in-law, György Adler, was the music director of Matthias Church from 1839 until his death in 1862. During the tenure of Adler’s successor, Ferenc Váray, the previously high musical standards began to decline. However, the musical activity of the church soon experienced a revival during the service of Mihály Bogisich (1882–1898), who was both a priest and a composer. Bogisich reformed the ensemble’s practices. The revival went on under the leadership of Zsigmond Szautner (1844–1910) and Mór Vavrinecz (1886–1912), who were choir directors appointed by Bogisich.

Matthias Church Parish Archives

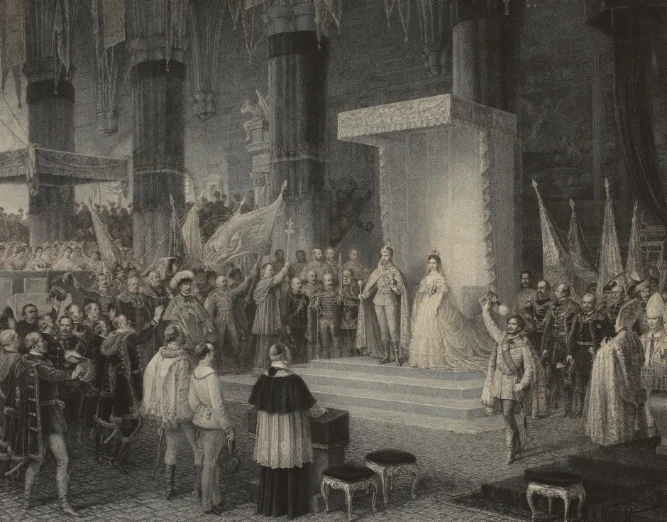

On 8 June 8 1867, Austria’s Emperor Franz Joseph and his wife, Elisabeth, were crowned King and Queen of Hungary at the Matthias Church. On this occasion, Ferenc Liszt’s Hungarian Coronation Mass (S11 / R487) was performed. Liszt was commissioned by János Scitovszky, Archbishop of Esztergom.

Hungarian National Museum Public Collection Centre Hungarian National Museum, The Graphic Collection

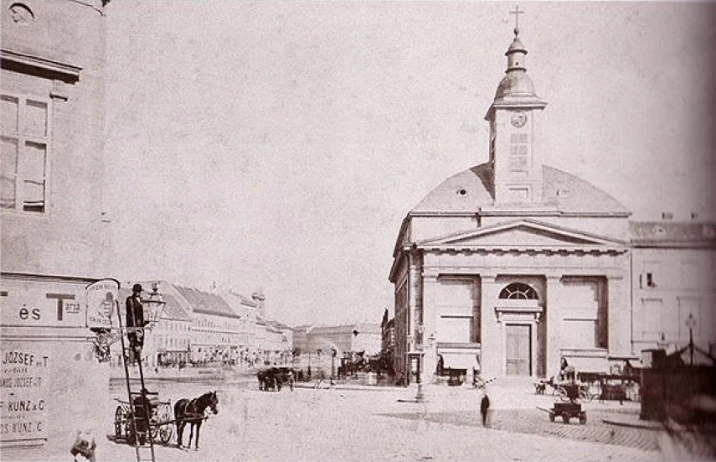

Pest’s Most Important Catholic Churches

Three parish churches in Pest-Buda had musical masses in the first half of the 19th century: the Pest Inner City parish church, the Church of the Assumption of Blessed Virgin Mary (today’s Matthias Church) in the Castle District, and Saint Anne’s parish church of Upper Watertown. These places had professional, i.e. paid choir and orchestra. In addition, there was also a paid ensemble in the parish church of Terézváros, but the number of performances decreased from 30–40 per year at the beginning of the century to only 8 in the middle of the century. Of course, figurative music was also played, on the major feasts, in a number of churches in Pest-Buda: in Buda, at the parish churches of Krisztinaváros and Tabán as well as at the Országút Franciscan church; in Pest, at the parish churches of Józsefváros, Ferencváros, and the Franciscan church. According to scattered data, large ordinaries were performed in both the Servite Church and the University Church, too.

The Inner City parish church of Pest had, in the first half of the 19th century, a rich liturgical life: masses were celebrated every hour on Sundays and holidays, as well as on weekday mornings. Figural music with the choir and orchestra could be heard at the Sunday solemn masses and at the Sunday afternoons vespers. The choir was generally made up of amateur musicians, while the orchestra consisted of professional musicians from the city’s most prestigious musical institutions of the time: the Pest-Buda Musicians’ Society, the National Conservatory, and the National Theatre. The flourishing music life of the church in the mid-19th century was due to the work of Kapellmeister Ferenc Bräuer who, in addition to his church musical activities, played a decisive role in the development of civic music life, including the founding of the National Conservatory and the Philharmonic Society.

FSZEK Budapest Collection

Fortepan/Budapest City Archives/Klösz György photos

Minor Churches with a Long Tradition

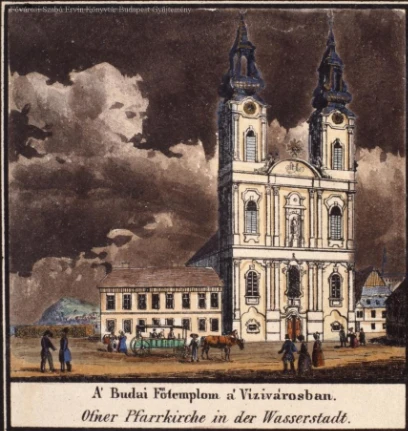

The Saint Anne parish church of the Upper Watertown, built between 1740 and 1746, initially borrowed musical instruments from the main parish church of the Assumption of Blessed Virgin Mary (today's Matthias Church), which was all the more handy as Jesuits led both churches. Nevertheless, Saint Anne soon established its own vocal and instrumental ensembles able to provide the figural service required at the time. As a result of these efforts, by the time the Jesuits were disbanded in 1773, the Saint Anne became Buda’s second most active church music center—after the Church of the Assumption—and carried on this rich tradition well into the 19th century.

Vasárnapi Ujság, 1865.07.23. 12/30, 373.

Similar cooperation existed among musicians of further parish churches and religious churches. Certain organists often served in more than one church, and so did singers and instrumentalists, too, on major feasts. Such interaction characterized the Servite Church in Pest and the Archdiocese Church of the Inner City. In addition to its vocal-instrumental church music practice, which became permanent from 1742, the Servite Church also became a prestigious “concert hall.” Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis was performed there on 26 July 1834. The piece remained in the repertoire for many years, with another performance, recorded by the press, in 1855.

Magyarország és a Nagyvilág 11/16 (1875.04.18.), 191.

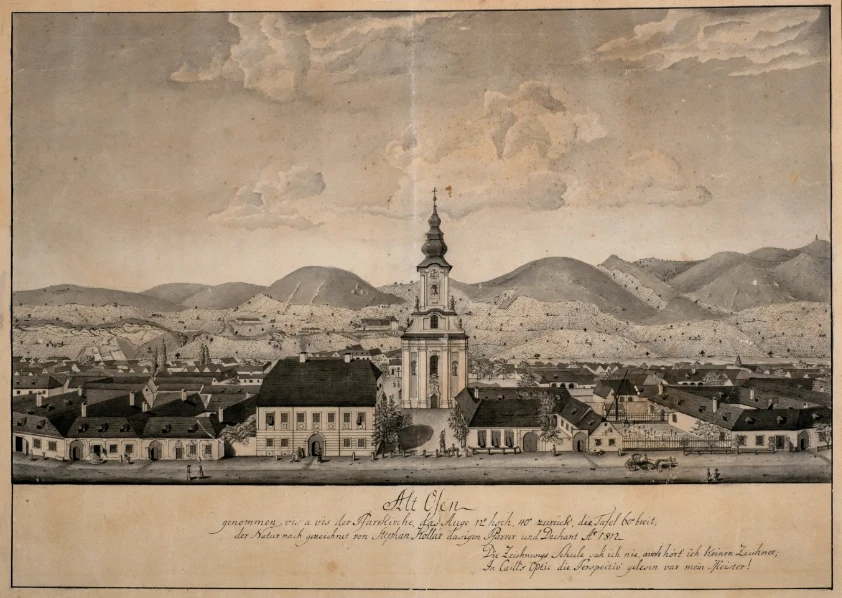

Óbuda’s Saint Peter and Paul parish-church was built between 1744 and 1749 in a peripheral area on local initiative and with the financial support of the Zichy-Bercsényi family. Among its musical feasts, the dedication church fair, held on the patron saints’ day, counted as a prominent event.

BHM Kiscell Museum, Municipal Gallery

Lutheran and Calvinist Churches

The Calvinist Church on Kálvin tér was built between 1816 and 1830 as the main church of Pest-Buda’s Hungarian-speaking Reformed congregation. This institution became a Hungarian national symbol in a city previously dominated by the Roman Catholic community with a majority of German-speaking believers. Its representative character demanded the construction of a grand organ. After the first six-stop Heroteck organ, a new instrument arrived in 1829 from the Deutschmann workshop in Vienna. With its two-manual and 24-note pedal, this instrument was one of the largest and most modern organs in Hungary at the time. At the London World Exhibition (1871), musicians from several countries were invited to perform at the Royal Albert Hall, on an instrument built by Henry Willis & Sons. In April 1871, Vince Lohr won the Hungarian competition organized at the Kálvin tér organ under the presidency of Ferenc Liszt in order to select the organist who would represent Hungary in London. In 1891, József Angster transformed the instrument into a three-manual organ with 35 stops—once again making the Kálvin tér organ the largest in Budapest.

Budapest City Archives

The Bach cult, which is still alive in the Lutheran church on Deák tér, dates back to the early 19th century. János Molnár (1757–1819), the first minister of the congregation, studied in Jena with Johann Nikolaus Forkel (1749–1818), the author of the famous Bach biography of 1802. In 1818, Molnár published with his own “Preface” Forkel’s study about church choirs, which also dealt with the singing of Bach’s chorales and cantatas. The male choir of the church was founded in 1862 and supported congregational singing from the organ loft, as hymnals at the time contained no music, only the lyrics. The choir sang four-part arrangements based on Bach chorales, harmonized by Mihály Mosonyi (1815–1870). Lutheránia Choral Society was established 1904, and remains active to this day; its first conductor was Frigyes Bruckner, the congregation’s cantor from 1900 to 1918.

The Synagogue

Although Óbuda officially became part of Budapest only in 1873, its synagogue, built in 1821 to the design of András Landherr, was already considered decades earlier a symbol of the Jewish population of Pest-Buda. Abraham Salomon Wahrmann, the community’s cantor for several decades, was also responsible for the music on the Emperor’s anniversary commemoration: in the summer of 1856, he was responsible for the rehearsal and the performance of the national anthem and the festive choral songs in the Israelite prayer house.

Magyarország és a Nagyvilág (8/39), 1872.09.29., 462.

From the middle of the 19th century – in parallel with the settlement of the Israelite population in Pest – the construction of the Dohány Street synagogue began. A few weeks before the consecration (6 September 1859), the press reported on the musical rehearsals for the ceremony, highlighting the exceptionally beautiful baritone voice of chief cantor Mór Friedmann. Thanks to him, the liturgy in Hungarian and with organ accompaniment was started in this church.

Magyarország és a Nagyvilág (8/39), 1872.09.29., 463.

Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches

The Serbian Orthodox Church of St. George the Martyr (4 Szerb utca [lit. Serbian Street]) was built by Serbian settlers who fled, due to the Ottomans, to Hungary at the end of the 17th century. On its site, a new church was built, which took its final form in 1752, when the bell tower was completed; this building can still be seen today. Initially, the Greek and Macedonian merchants settled in Pest also visited this church, but as they grew in number, the need for a church of their own arose. Consecrated in 1801 as the Church of the Assumption of the Mother of God (Assumption), this impressive church was built on a plot of land by the embankment of the Danube, bought from the Piarists. The Serbian Cathedral, Buda’s most important Orthodox church, had adorned since 1775 the Tabán District, then known as Rácváros [lit. Serbia Town]. In 1810, its furnishings were destroyed in a fire, but when it was rebuilt in 1824, the Serbian community of Buda was able to reclaim its main church. The building, which stood on today’s Döbrentei tér was badly damaged in the Second World War, then it was demolished in 1949. Catholics of the Byzantine rite began to move in large numbers to the Hungarian capital in the second half of the 19th century. Once their application for an own church was approved of by the Ministry, the Greek Catholic Parish of Budapest was established in 1905 in the building of the Roman Catholic Church in Szegényház tér (today’s Rózsák tere). From the beginning, Orthodox liturgy in Hungary was based on the chant tradition and language of the respective mother churches. Only after the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries have Hungarian-language hymns and translations into Hungarian become part of the musical material used in the services.

BHM Kiscell Museum, Photo Collection.

Fortepan / Budapest Capital Archives

![4 Szerb utca [lit. Serbian street], The Serbian Church of Pest in 1954](/images/loc-33.webp)

Fortepan / Tibor Geuduschek

Fortepan / Budapest City Archives

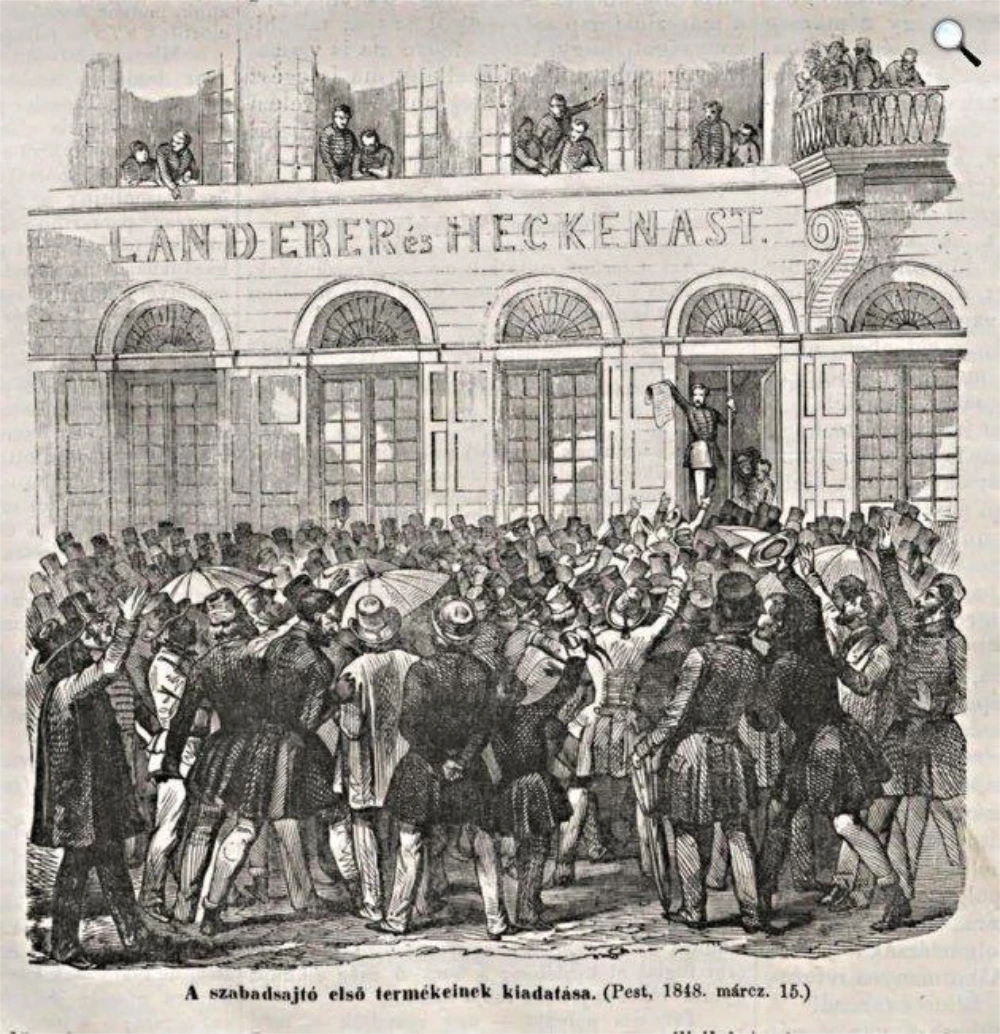

The First Music Publishers

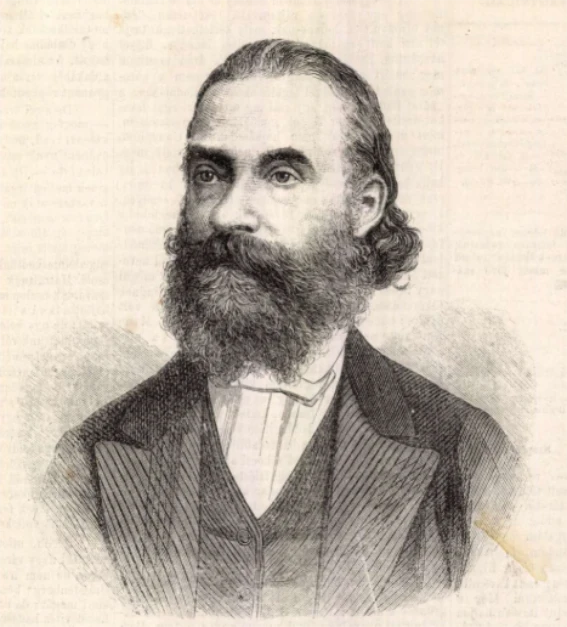

The music publishing industry, which flourished in Vienna since the 1780s, soon found its way to the larger cities of the Kingdom of Hungary, especially Pozsony and Pest-Buda. The first music dealers in Pest-Buda initially operated as branches of Viennese companies. However, in the first decades of the 19th century, as demand of bourgeois music-lovers grew, independent publishers also settled in the capital. One of the most successful was the book and music store founded in 1839 by József Wagner, who became known for publishing works by Erkel, Egressy, Rózsavölgyi, and Doppler. Wagner was the first to publish Erkel’s setting of Kölcsey’s Hymnusz in September 1844, which had won the National Theater’s competition.

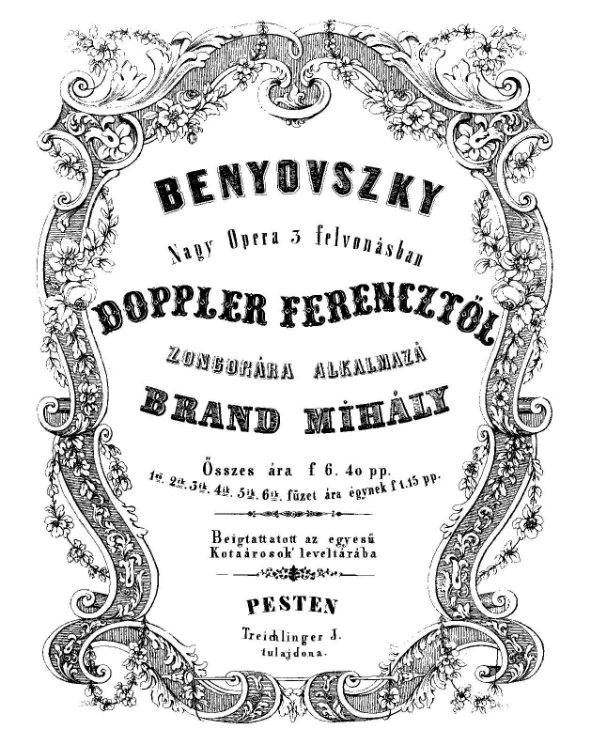

József Treichlinger bought Vince Grimm’s publishing house in 1843, but due to objections from József Wagner, he did not receive official permission to continue publishing until 1845. In 1852, Magyar Hírlap described Treichlinger as someone who had rendered outstanding services to the dissemination of Hungarian popular music in general: His name is primarily associated with the publication—in arrangements for voice and piano—of popular folk songs of the time, which also appeared in folk plays. He published works by Ferenc Doppler, Gyula Szénfy, and Béni Egressy, as well as piano score of Ferenc Erkel’s opera Hunyadi László.

![Hymnusz, költemény Kölcsey Ferencztől. Koszorúzott zenéjét írta [...] Erkel Ferencz. Published by Wagner József.](/images/loc-36.webp)

The Rise of Music Publishing

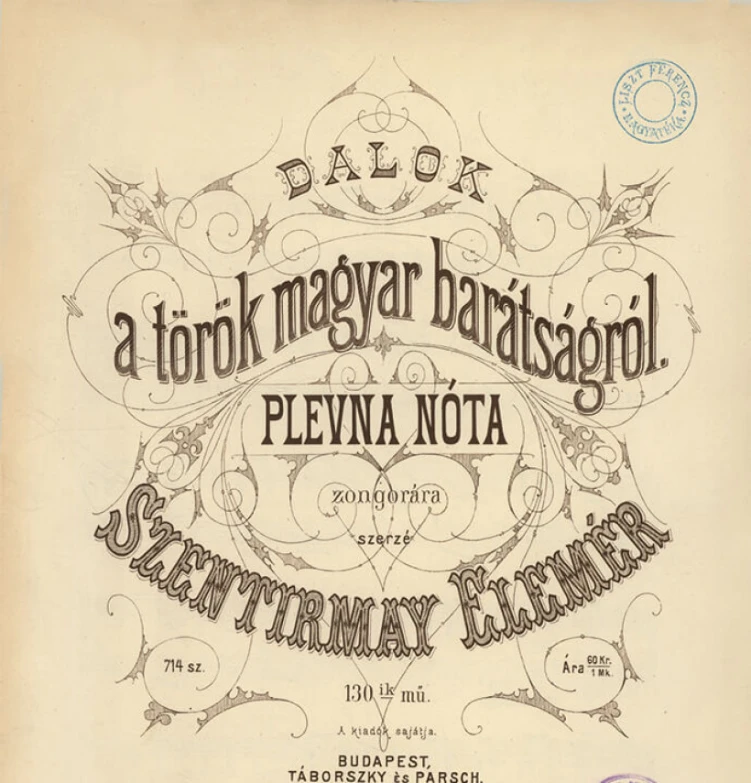

The Rózsavölgyi & Co music publishing house was founded in 1850 by Gyula Rózsavölgyi (son of the great verbunkos musician Márk Rózsavölgyi) and Norbert Grinzweil. The publishing house saw its mission in both preserving national musical traditions and performing new music. They published the works of the most famous contemporary authors such as Erkel, Liszt, Mosonyi, and Volkmann. In the second half of the 19th century, the publishing house developed into Hungary’s largest music publisher, with its headquarters in Budapest’s downtown area (first on the corner of what is now Széchenyi tér and József Attila utca, then on today’s Petőfi utca, and later on Kristóf tér). From the outset, the publishing house was also involved in organizing concerts. Nándor Táborszky founded his music publishing business in 1868 as a branch of the Rózsavölgyi publishing house, but soon became independent. With József Parsch, he founded the Táborszky and Parsch publishing house, which operated until 1895. Táborszky was a personal acquaintance of Ferenc Liszt, and his company is also referred to as Liszt's favorite Hungarian publisher; they published several works by Liszt.

Society of Composers as a Business Venture: Harmónia Joint-stock Company

Hungarian Musicians’ Harmónia Music Publishing House, the first company supporting Hungarian composers was founded in October 1881 under the leadership of Jenő Hubay and his brother, Dr. Károly Hubay. According to a newspaper notice – published on behalf of Harmónia Comp. and signed by Ede Bartay, Károly Huber, István Bartalus, Imre Székely, Alajos Gobbi, Jenő Hubay, and Károly Aggházy – the main activities of the company consisted of music publishing, concert organizing, as well as music trading and the sale of pianos and stringed instruments on consignment. The joint-stock company became successful: within a few weeks, its first three hundred shares were sold entirely (Ferenc Erkel also bought some), so they were able to quickly raise the initial capital needed to start their operations. For several decades, Harmónia published sheet music and organized concerts.

Magyar Kereskedelmi és Vendéglátóipari Múzeum

Musical Press in German

Not only the Hungarian-language press but also the German-language press played a significant role in the Hungarian public sphere in the 19th century. These editorial offices assumed not only cultural but also political and social roles. The press is one of our most important sources for music history: through everyday reports such as reviews, news, and advertisements, the musical life of the time can be reconstructed in great detail.

Several newspapers operated to serve the German-speaking readership. The most prestigious among them was the Pester Lloyd. As the official newspaper of the Lloyd Trading Company, it was based in the Hild Palace located at the Pest end of the Chain Bridge. Many members of the Lloyd’s editorial staff were actively involved in musical life; for example, Baron Gábor Prónay, a former president of the National Conservatory, was a regular contributor to the paper. Advertisements in the empire-oriented Pesth-Ofner Localblatt also provide insight into the operation of music venues and open-air concerts.

Fővárosi Szabó Ervin Könyvtár

Musical Press in Hungarian

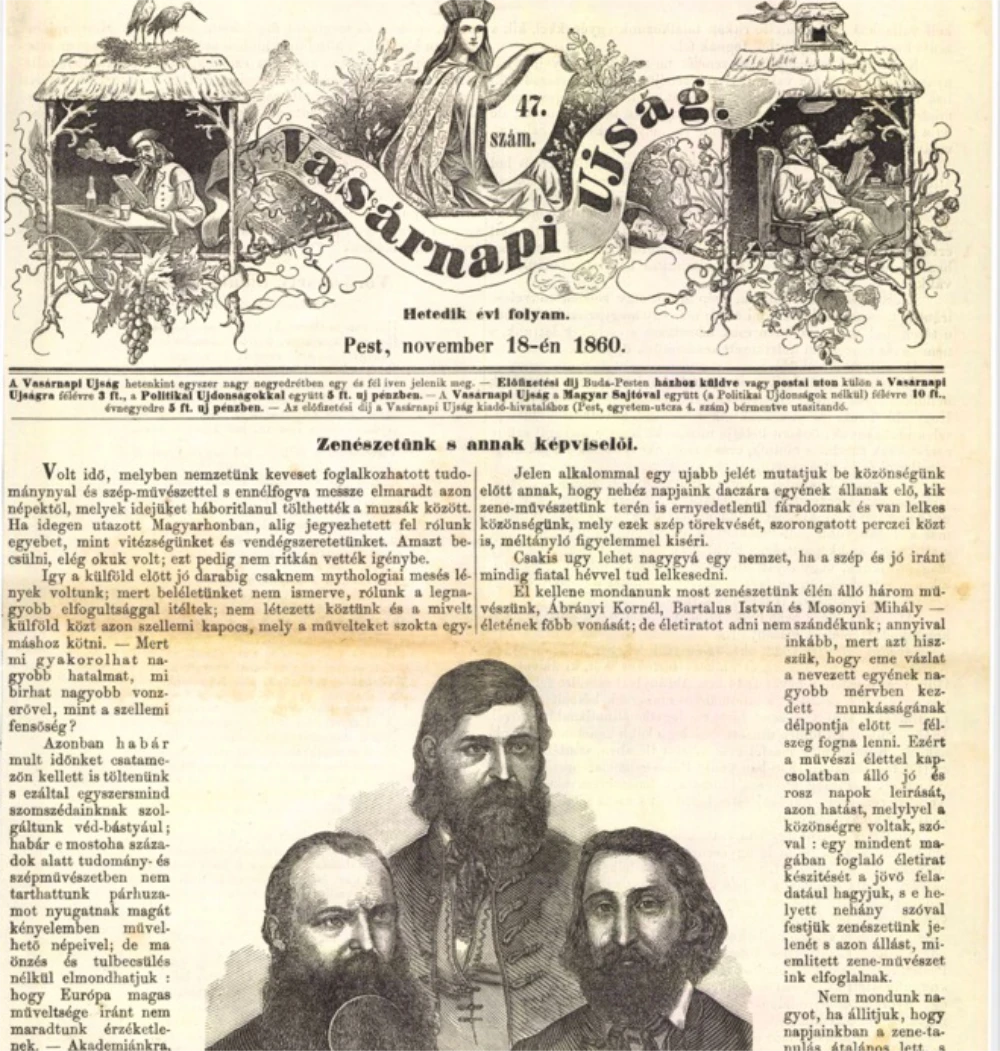

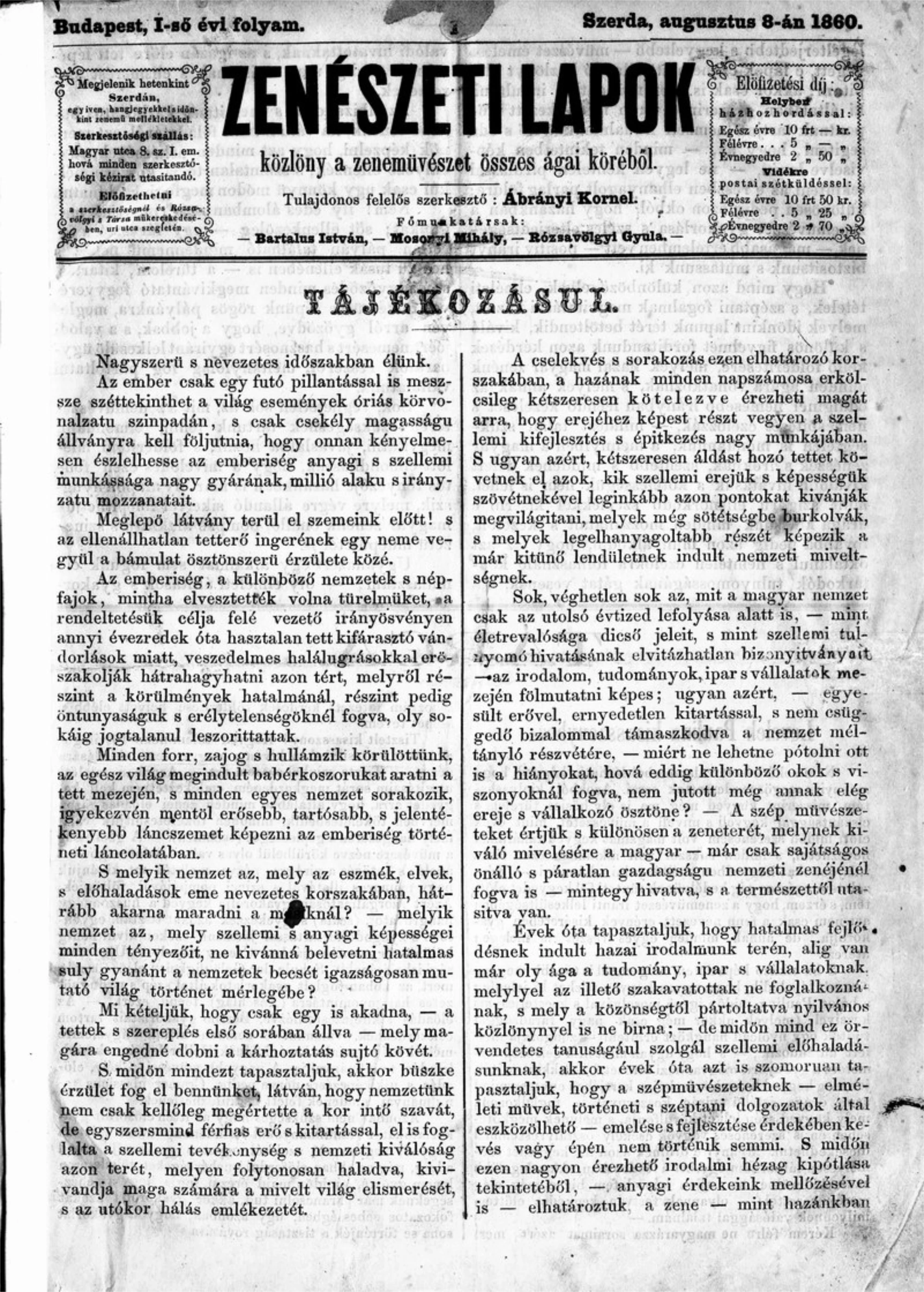

The first musically themed articles, e.g. news and concert announcements, appeared in Magyar Hirmondó, the first Hungarian-language newspaper, launched in 1780. Their number steadily increased during the early 19th century. By the 1850s, as public and semi-public events organized by civic music institutions (such as theatres and concert societies) became more common, music criticism gained a prominent role, especially in the feuilleton sections of literary and arts journals. In 1853, Szépirodalmi Lapok [Literary Journal] featured regular opera and concert reviews by music columnist Sámuel Brassai, who published under the pen name “Canus.” Hölgyfutár included the reviews in its “National Theatre” column, while Vasárnapi Ujság featured musical theatre and opera criticism in both the feuilleton section and writer Mór Jókai’s column, “Kakas Márton.” Zenészeti Lapok, the first journal dedicated to Hungarian music, appeared in 1860. Its Editor-in-Chief, Kornél Ábrányi Snr., also published music criticism in a number of non-musical newspapers and magazines, such as Pesti Napló, Budapesti Hírlap, Fővárosi Lapok, and Magyar Salon.

Vasárnapi Ujság [Sunday Times] (18 November 1860).

![Szépirodalmi Lapok [Literary Journal] (21 April 21, 1853.)](/images/loc-42.webp)

Vasárnapi Ujság, (4 January 1863), 10/1, 5.

Vasárnapi Ujság, (15 March 1868), 15/11, 124.

First music journals

Zenészeti Lapok was Hungary’s first music magazine, published from October 1860 to August 1876. Its editor-in-chief was Kornél Ábrányi Sr., and its most important contributors at the beginning of the magazine were István Bartalus, Mihály Mosonyi, and Gyula Rózsavölgyi. Ábrányi’s program was to create a Hungarian art music style in line with European standards, to develop a bourgeois concert culture, and establish a Hungarian musical language. The magazine’s issues dealt primarily with music theory and aesthetics, but they also reviewed Hungarian musical works, in addition to musical news. From January 1869 to the end of 1872, the newspaper was the bulletin of the National Hungarian Singing Association. Ábrányi then reacquired the property rights in order to re-create an “independent, autonomous music magazine.”

Salons of Composers and Musicians

In the second half of the century, more and more salons opened in Pest, becoming the central piece of the bourgeois apartment, where the presence of a piano was obligatory. On the music stand, one can see Imre Székely’s Magyar ábránd [Hungarian Fantasy]. In addition to the most famous literary salons, such as the Wohl and Pulszky salons, Budapest also boasted a number of notable music salons. At the end of 1870, Ferenc Liszt held his Sunday matinées at the Inner City Parish Church of Pest, and later such prestigious musical gatherings were held at his quarters located in the building of the Music Academy. Imre Székely had held matinees earlier, where his students played. These events were often reported in the press, but diaries and correspondences also tell us about private civic music salons. The Hellmesberger String Quartet held their Pest rehearsals at the Gáger residence; the apartment of Norbert Grinzweill, co-founder of Rózsavölgyi and Co., was also a frequent haunt of the musical world in Pest.

![Ferenc Liszt’s study in Budapest (drawing by Gyula Széchy). The drawing shows Liszt’s apartment in the Vörösmarty utca Music Academy [today’s Old Academy of Music].](/images/loc-47.webp)

Magyar Salon 2/4 (1885), 568.

Aristocratic Salons

Bordering on 19th century’s private and public theatres, aristocratic salons seem an interesting milieu with musicians and artists also appearing as guests – as a survival of the aristocratic patronage inherited from of previous century. During his visits to Hungary, Ferenc Liszt was a frequent guest in the palaces of his aristocratic admirers and a performer at their private concerts. On Christmas 1840, he stayed with Leó Festetics (9 Nádor utca); January 1841, he gave a charity concert for the benefit of the Institute for the Blind in Gábor Keglevich’s salon in Buda (40 Herrengasse / Úri utca). Guido Karátsonyi, too, invited the composer to his Krisztina town / Christinenstadt palace (55 Krisztina körút) in 1856, during the premiere of the Gran Mass. Baron Antal Augusz, Liszt’s closest friend, hosted the composer several times in his house in Buda (43 Herrengasse / Úri utca). Contemporary press often mentioned music loving Archduchess Hildegard, also known for her charity work. In 1852, for example, she attended a performance of I due Foscari at the National Theatre. In 1858, she was in the audience of Clara Schumann’s farewell concert.

Vasárnapi Ujság, 32/38 (1885.09.20.), 608.

Vasárnapi Ujság, 49 (1856.12.07.), cover

Ábrázolt folyóirat [Képes Újság], 1/3 (1848.01.15.), cover

Vasárnapi Ujság 11/34 (1864.08.21.), 345.

Bourgeois Salons

Around the middle of the 19th century, Pest-Buda homes resonated with music, literature, and lively intellectual discussions. Janka and Stefánia Wohl, the two highly educated and polyglot sisters, were the hostesses of a celebrated salon, regularly attended by Ferenc Liszt, who also introduced Géza Zichy and later Jenő Hubay there. Antónia Bohus-Szőgyény’s residence on Sas utca was also frequented by renowned guests, including Ferenc Liszt, Antal Reguly, and Ágost Trefort. On 19 February 1856, Clara Schumann, who gave several performances across the city, also held a concert there. One of the most popular social venues of the 1850s was the salon of Kornélia Hollósy, the National Theatre’s celebrated opera star. Ferenc Erkel was among her regular guests. In Antal Csengery’s literary circle, Etelka Gönczy played the piano. Her appearances at the salon of Pál Gönczy, i.e. her father, were enjoyed by Ferenc Erkel and Sámuel Brassai among others. In the 1870s, museum director Ferenc Pulszky held Saturday evening gatherings at his own residence, located within the building of the Hungarian National Museum. Music was often part of these evenings and Ferenc Liszt was a frequent guest. In one of her letters, Polyxena Pulszky, the daughter of Ferenc Pulszky, wrote to Sándor Szilágyi that the Florentine Quartet would be performing at their home.

Vasárnapi Ujság (1889.11.03.), 36/44., 718.

Hungarian National Museum Public Collection Centre, Hungarian Museum of Trade and Tourism

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek

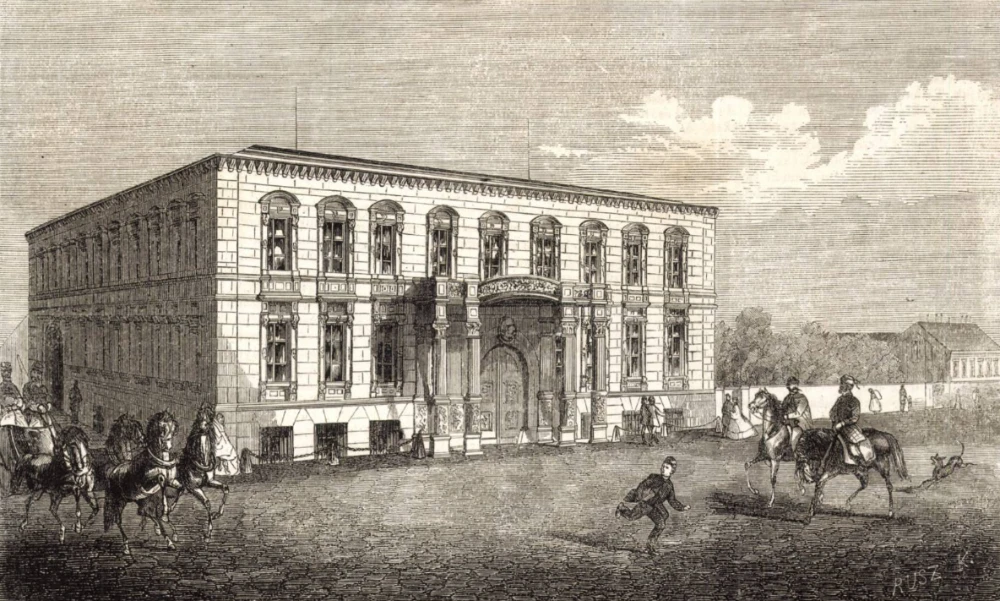

Choir Movement

Choirs founded in Germany and later throughout Europe followed the example of the Berlin Liedertafel (1809). By the middle of the 19th century, the choir movement also emerged in Hungary, acquiring an organized form already organized in the second half of the 1860s. The first choral societies in the Hungarian capital were founded in the 1840s, and from the 1850s onwards, more and more choral societies operated in Pest, Buda, and Óbuda. In the 1850s, the Pest-Buda Choral Society led by Nándor Thill, the Sängherhort (later the Buda Choral Society) and the Óbuda Choral Society were founded, followed by the Royal Hungarian University Choral Society in 1861 and the Pest Union in 1862.

As in other choral societies in the country, the activities of the Pest-Buda male choir societies were very diverse: public concerts (singing festivals, festive singing festivals, singing festivals with dancing entertainments, charity concerts), numerous semi-public events (flag consecrations, church services, serenades) and private events (e.g. excursions), as well as weekly choir rehearsals and singing lessons. Accordingly, the choir societies were present at many civic and church venues in the city: they performed in the Municipal Shooting Range, in the University Church, on Margaret Island, and in the Tüköry beer hall.

![Anniversary of the Magyar Daláregyesület [Hungarian Choral Society]. The 1865 Song Festival in the Városliget [City Park] in Pest.](/images/loc-55.webp)

Drawing by Gusztáv Keleti.

Restaurants

Thanks to new research, we now have a detailed view of how diverse the musical life of Pest-Buda—later Budapest—was in the 19th century. Cafés and beer gardens functioned not only as gastronomic venues but also as social and cultural spaces, where music played a central role. Romani bands and military orchestras performed regularly, but it was also common to hear Tyrolean folk groups or other foreign traveling musicians. Concerts in venues catering to various social classes were often referred to as “reunions” or “soirées.” Among the most popular establishments that offered musical entertainment were Zum Sieben Kurfürsten (“To the Seven Electors”) and the Goldener Anker (“Golden Anchor”), but Komlókert and the Tüköry Beer Hall were also considered favored locales.

Magyar Kereskedelmi és Vendéglátóipari Múzeum

Bathhouses

In the mid-19th century, the bathhouses of Pest-Buda served not only medicinal and recreational purposes but also functioned as important venues for social and cultural life. The musical life of the Császár Bath was particularly rich: concerts and elegant balls were regularly held on the premises, attracting mostly members of the domestic and international aristocracy, though the events were also open to the bourgeoisie. The building, still standing today and designed by József Hild, included an inner garden where a cast-iron kiosk was erected—this served as the performance space for musicians. In addition to performances by military and Romani bands, a dedicated bathhouse orchestra was also available, and a piano was provided for the comfort of bathing guests who wished to play. The Rácz Bath also occasionally hosted musical events.

![A Császárfürdő Budán / Das Kaiserbad in Ofen [The Imperial Bath in Buda]. After a drawing by Alt R. ; engraving by Sandmann. 1845](/images/loc-57.webp)

FSZEK Budapest-képarchívum

Edited by Katalin Kim.

Authors: Lili Veronika Békéssy,

Rudolf

Gusztin,

Pál Horváth,

Szabolcs Illés,

Beáta Simény,

Emese Tóth,

Zsolt Vizinger.

Translation: István Csaba Németh.