The First Signs of Early Music Playing in Hungarian Concert Life

Though not to the same extent as in Mendelssohn’s Berlin and Leipzig circles, efforts to historicize music appeared in Hungary’s musical life from the second half of the 19th century onward. Alongside renowned foreign artists, both the pioneers of Hungarian musicology and the directors of the reorganized musical societies played a significant role in promoting the musical treasures of earlier ages. The following selection focuses on the programming and reception of some of their earliest historical concerts held in Pest-Buda.

By the end of the 18th century, both the Hungarian aristocracy and bourgeoisie begun to view Vienna and its artistic movements as models worth following. However, the repressions coming after the suppression of the 1848 Revolution and War of Independence significantly diminished in Hungary, to put it mildly, the popularity of German-language culture mediated through the Viennese court. Consequently, musical historicism—a movement that had already gained momentum abroad— found its way to Hungarian audiences only decades later.

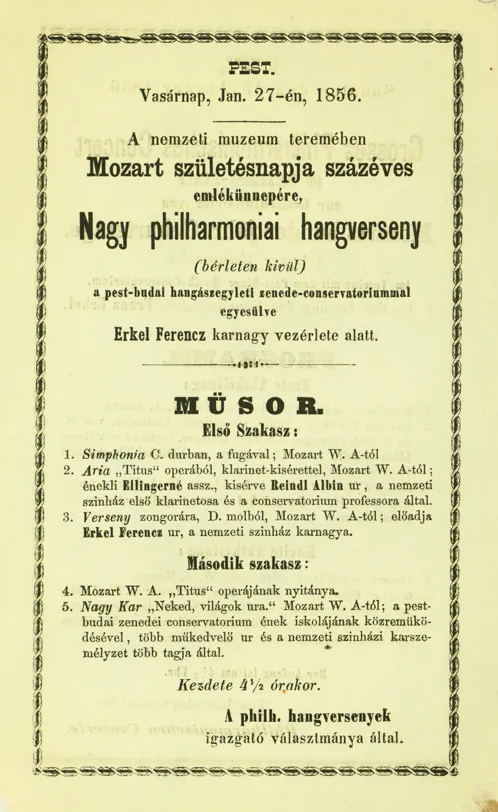

In parallel with the reorganized National Conservatory, which became one of the first and foremost institutions of art education in Hungary, a Philharmonic Society was also established in Pest in 1853 under the leadership of Ferenc Erkel. The Philharmonic Society joined the series of European events commemorating great figures of music history – including the memorial concert conducted by Liszt in Vienna – by organizing in Pest on 27 January 1856 an extraordinary symphonic concert to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Mozart’s birth.

If we consider thematic concerts commemorating famous composers of earlier times as part of musical historicism, the Philharmonic Society’s concert, featuring exclusively works by Mozart, was probably one of the first historical concerts in Hungary.

Archives for 20th–21st Century Hungarian Music of the Institute for Musicology, RCH HUN-REN

Prior to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, which gave a great impetus to both industrial and cultural development, it was not possible to establish civic associations that could have organized historical concerts and oratorio evenings, musical events that were already popular during the time in major European cities.

Nevertheless, the prevailing Zeitgeist favoured research into the nation’s past and cultural monuments. This period saw the emergence of the first writings of Hungarian music history, written by Gábor Mátray (Rothkrepf), István Bartalus, and Kornél Ábrányi Snr.

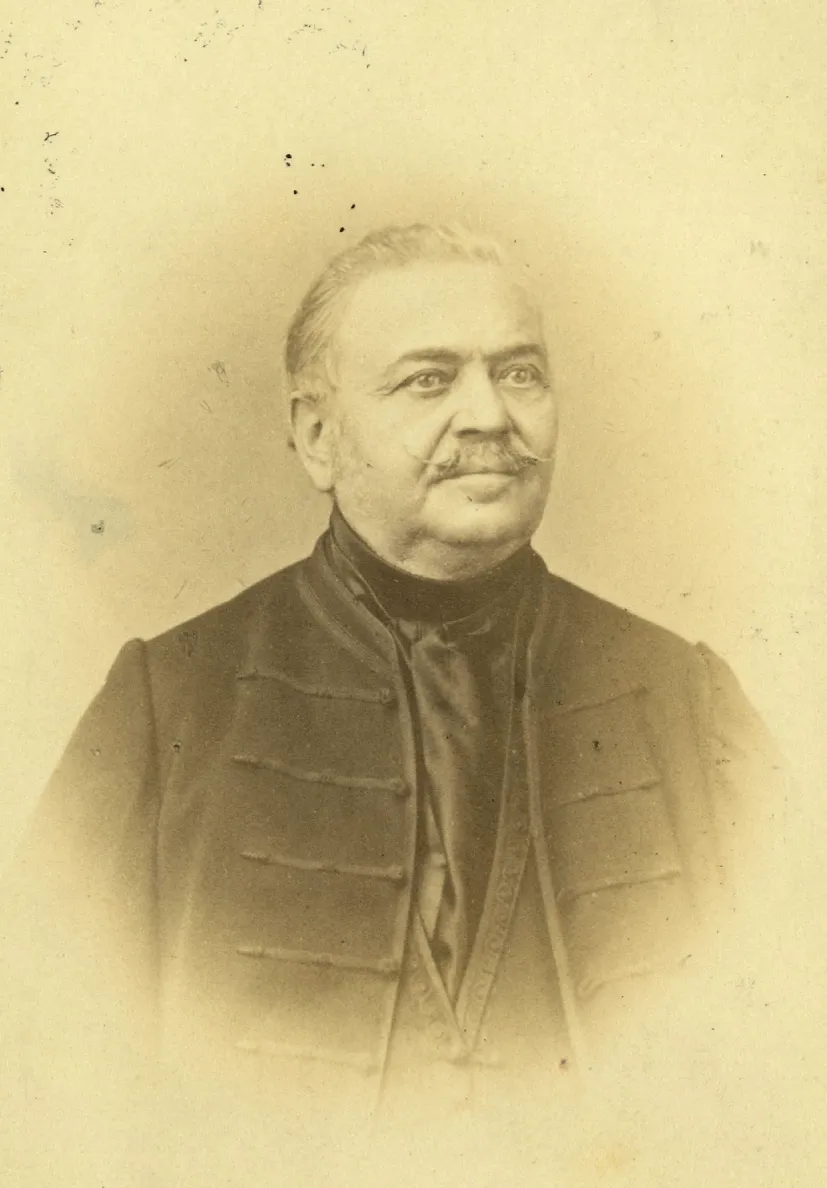

Photo: Ignác Schrecker (1865) Forrás: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library, bibFSZ01430562

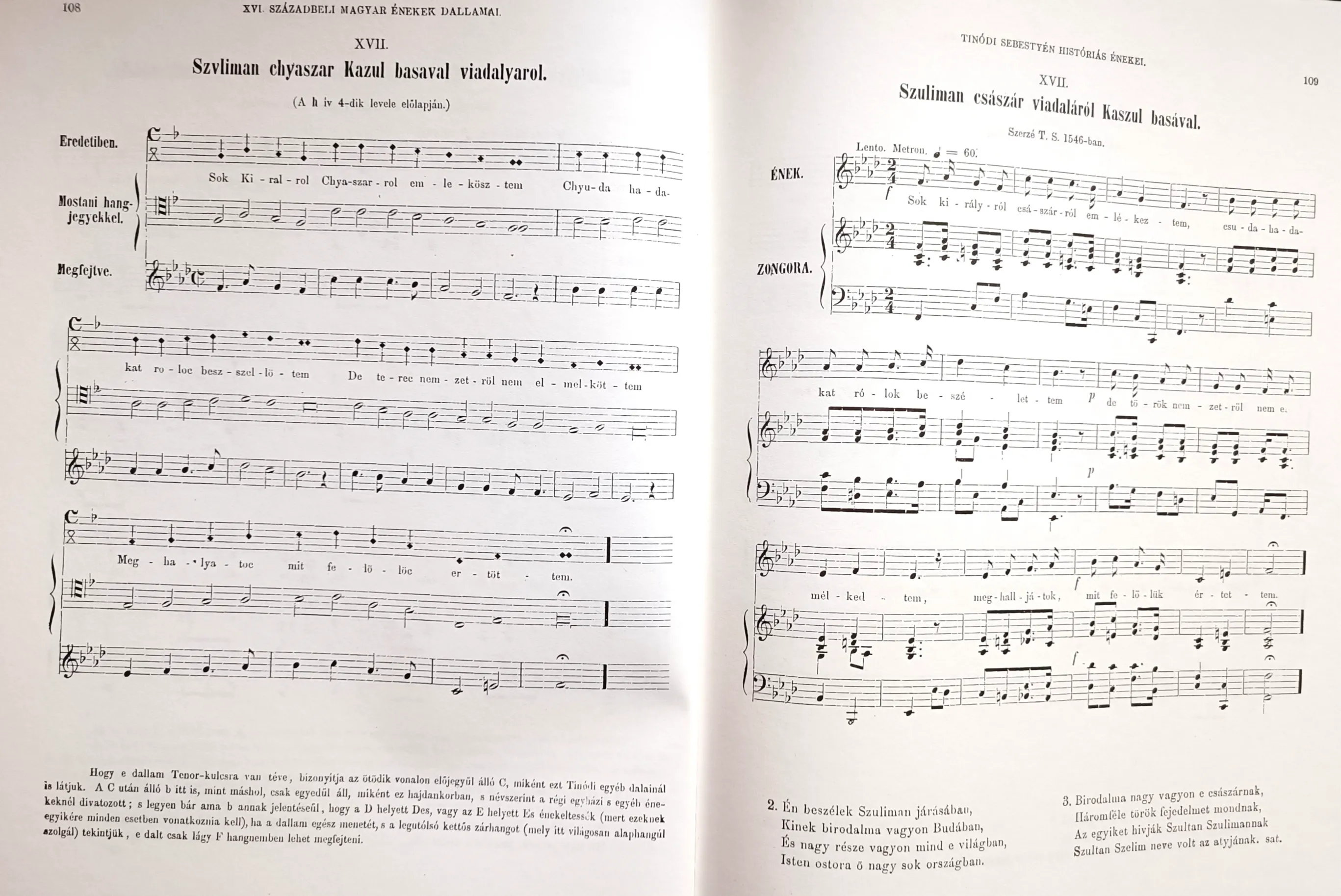

Mátray – the director of the National Conservatory, the guardian of the National Museum’s (later: National Library’s) historical collections, and a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Music - made important contributions to the rediscovery of Hungary’s musical heritage. As part of his efforts, Mátray studied ancient codices, transcribed and published his own folk music collections. In 1852, he delivered a lecture on the works of 16th-century lutenist Sebestyén Tinódi Lantos, then, in 1859, Mátray published his Tinódi-transcriptions and, on 13 March of the same year, he gave a concert in the Lloyd Hall with the students of the National Conservatory.

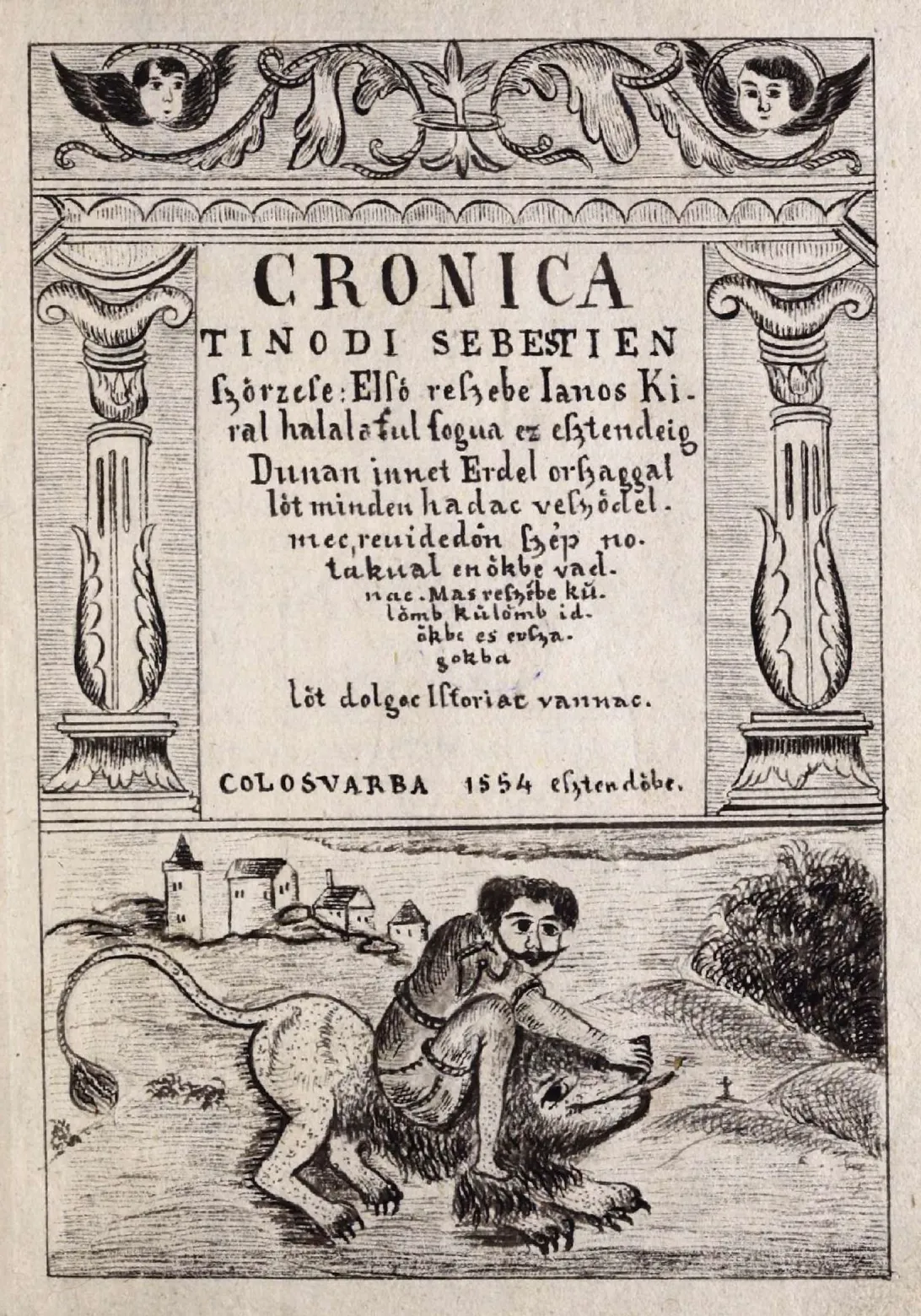

MNMKK OSZK RMK I. 33.

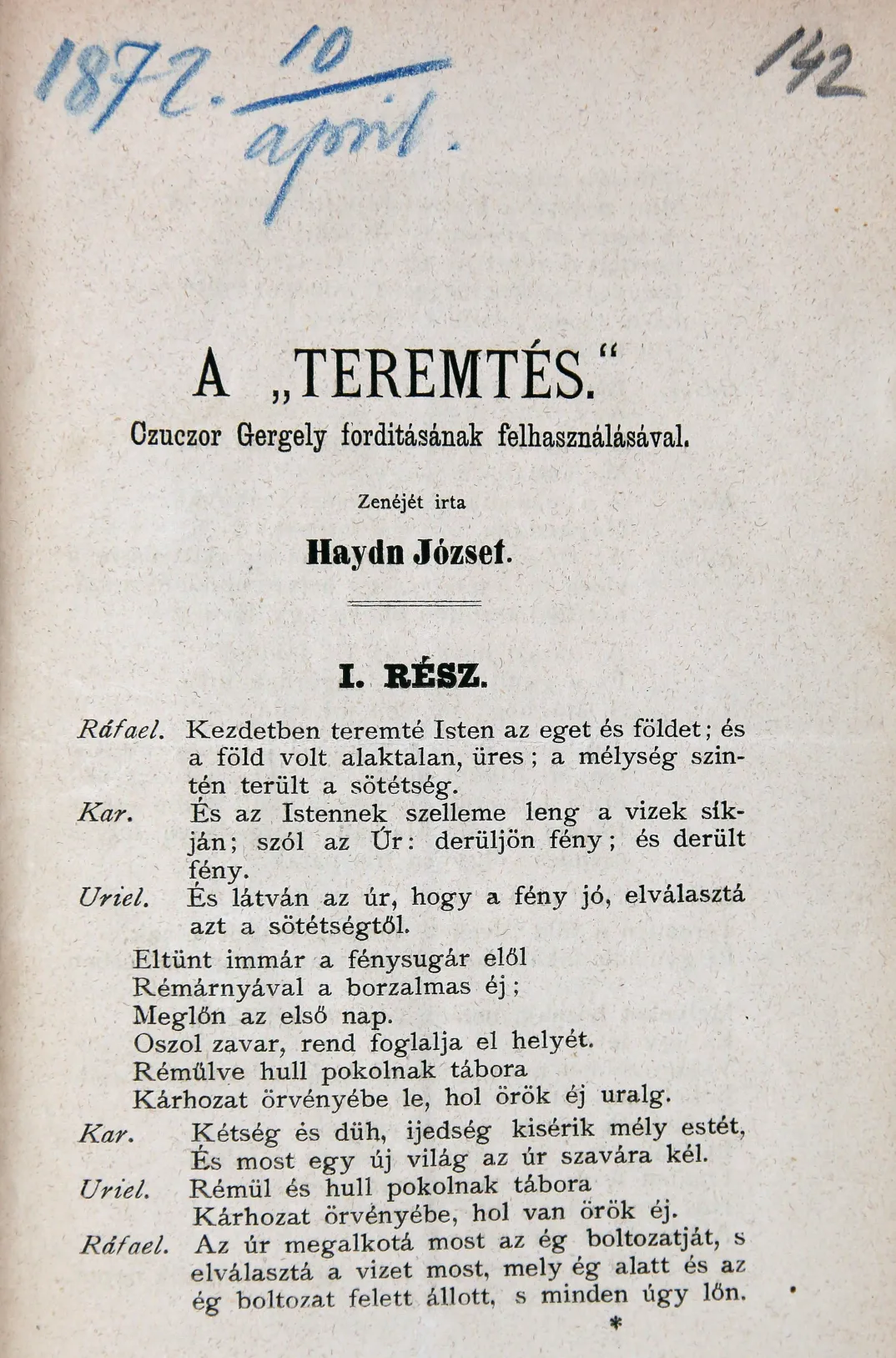

Tinódi’s volume of songs – originally published in print in the year 1554 by György Hoffgreff in Kolozsvár (source: H-Bn RMK I. 112) – is one of the earliest known printed music editions in Hungary. The author was the most famous bard of our country, whose songs reported on the battles and historical events of the Turkish occupation. Tinódi’s period notation, with its enigmatic clefs and missing rhythm caused no small amount of puzzlement even to the most skilled musicians of the 19th century. Mátray’s edition contains a number of errors based on misunderstood key signatures and accidentals; moreover, he spiced up the rhythm and melodic profile of the individual songs relying on the popular art songs of his own period.

Photo: Josef Löwy (1865) Forrás: Wien Museum, Online Collection 73315/58

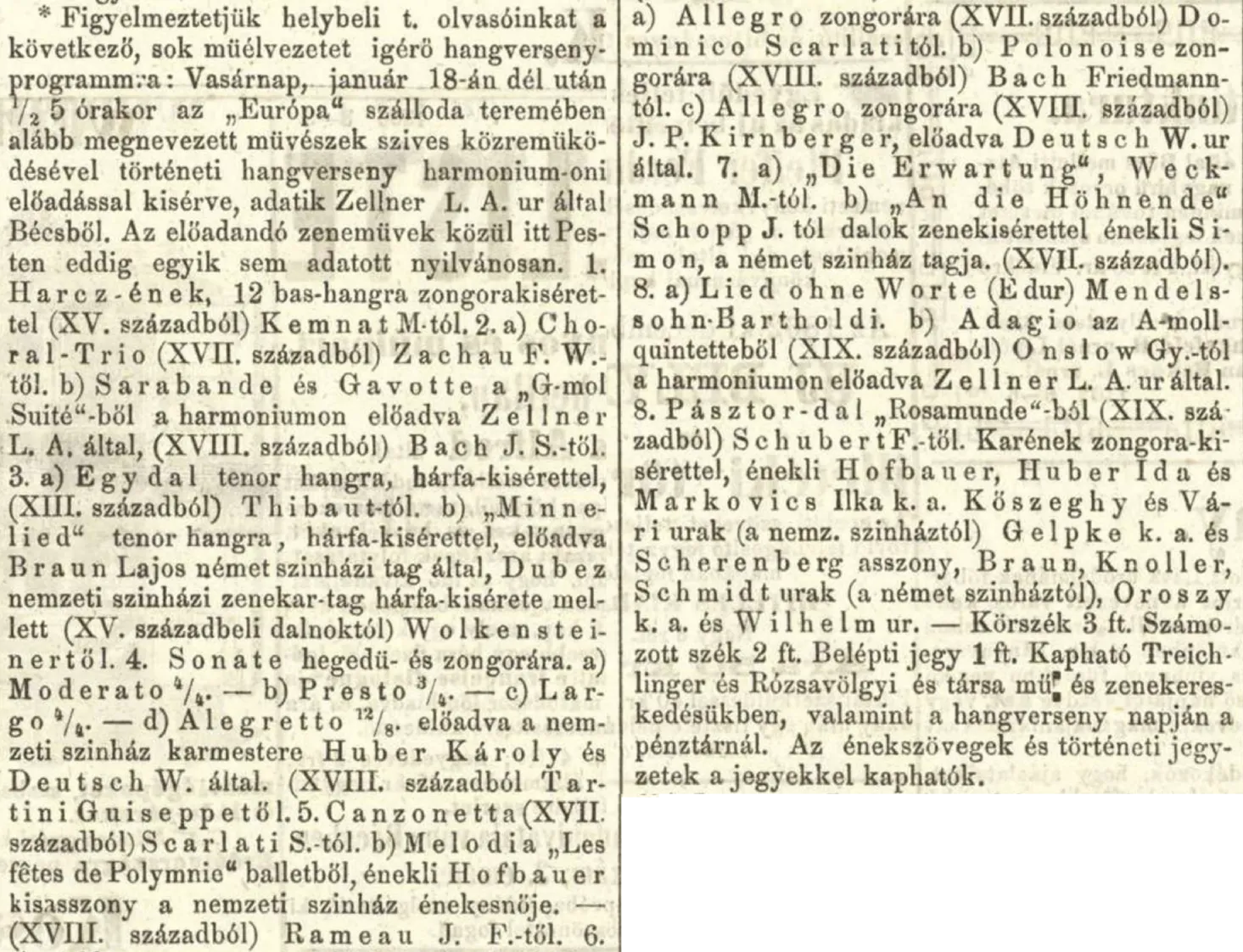

A few years later, the Pest-Buda audiences, hungry for cultural delicacies, witnessed another special concert. On 18 January 1863, Leopold Alexander Zellner, the Secretary of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna – at the same time an infamous concert critic and a harmonium virtuoso – presented a genuine “historical concert,” which featured, according to press advertisements, works spanning from the 13th to the 19th centuries never before heard in Pest.

The press coverage of Zellner’s presentations on similar themes in Vienna, which he had held regularly since 1862, created great anticipation among the local audience, and the number of distinguished Hungarian artists invited to the concert as well as the intriguing and varied program announced in detail, managed to increase the interest.

Pesti Napló, 17 January 1863.

The concert featuring pieces from seven centuries, which would be a curiosity even today, was highly acclaimed. For the first time, Hungarian audiences were able to experience the history of European ancient music in a live performance.

As proof of Zellner’s unflagging interest in music history, he played two Tinódi arrangements by Mátray as encores to his first concert in Budapest, and on his return, a year later, he would present these two songs heard here as part of his concert program.

Performed by Ágoston Tóka

Library of Musicology of the Institute for Musicology, RCH HUN-REN, 241.390

Performed by Ágoston Tóka

Library of Musicology of the Institute for Musicology, RCH HUN-REN, 241.390

This was a real “historical concert,” despite the fact that the instrumentation of the various pieces and the elaboration of the basso continuo-parts reflected 19th-century taste, as was common at the time. The gentle breeze of historicism in Zellner’s concerts had only touched the music life of the capital, but the Hungarian press referred, even later years, to the positive influence of the harmonium virtuoso as a stylistic innovator.

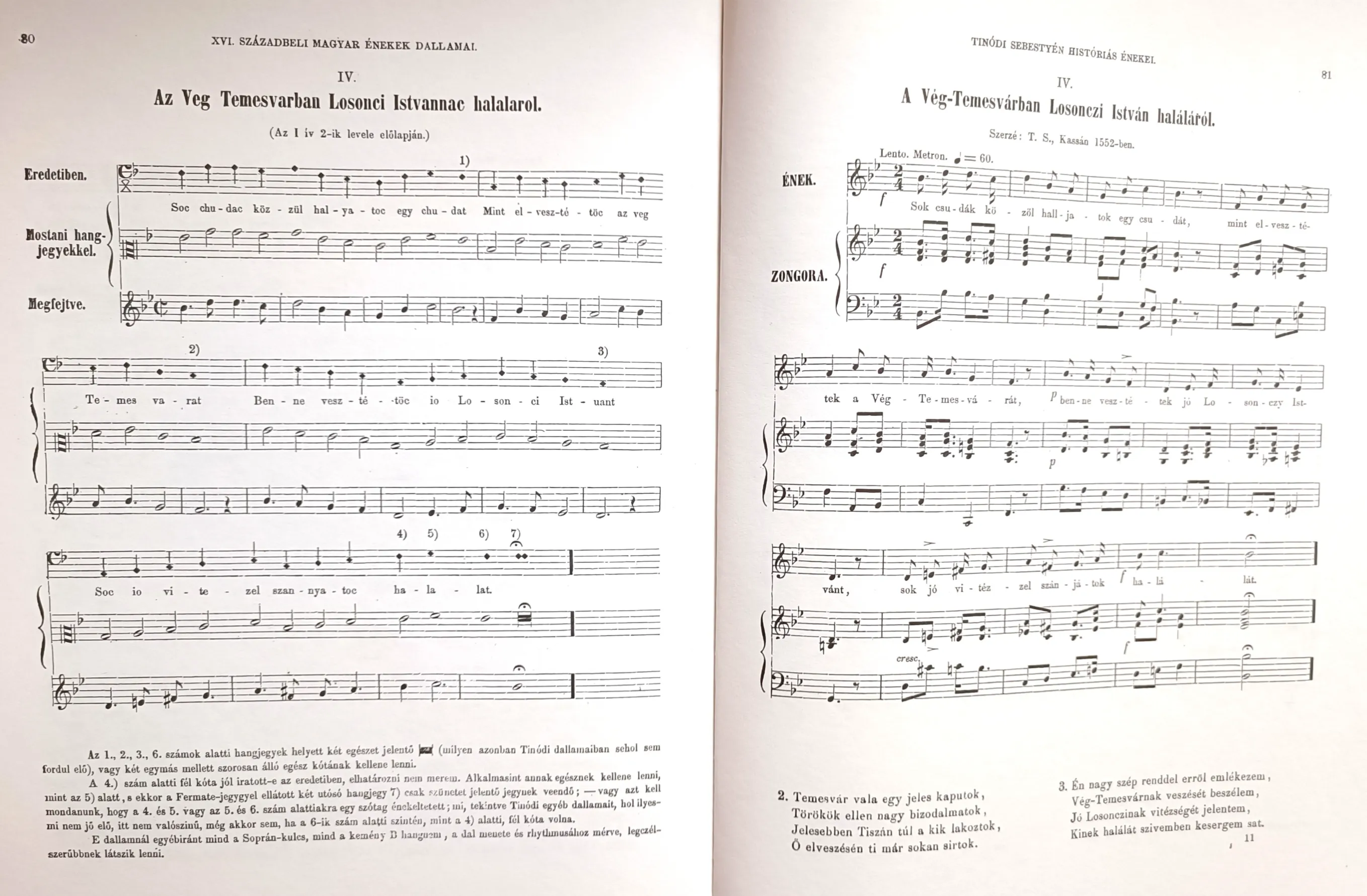

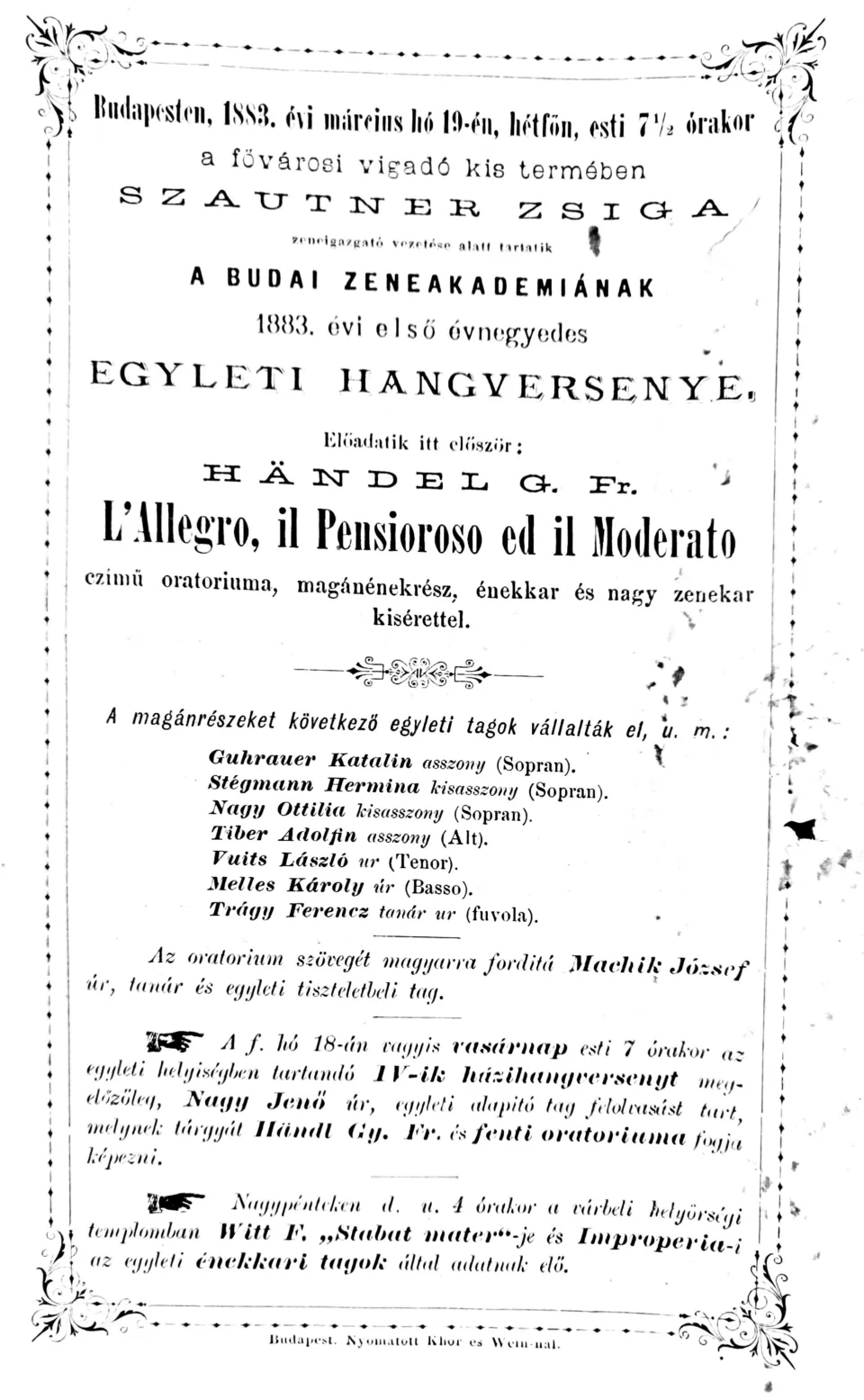

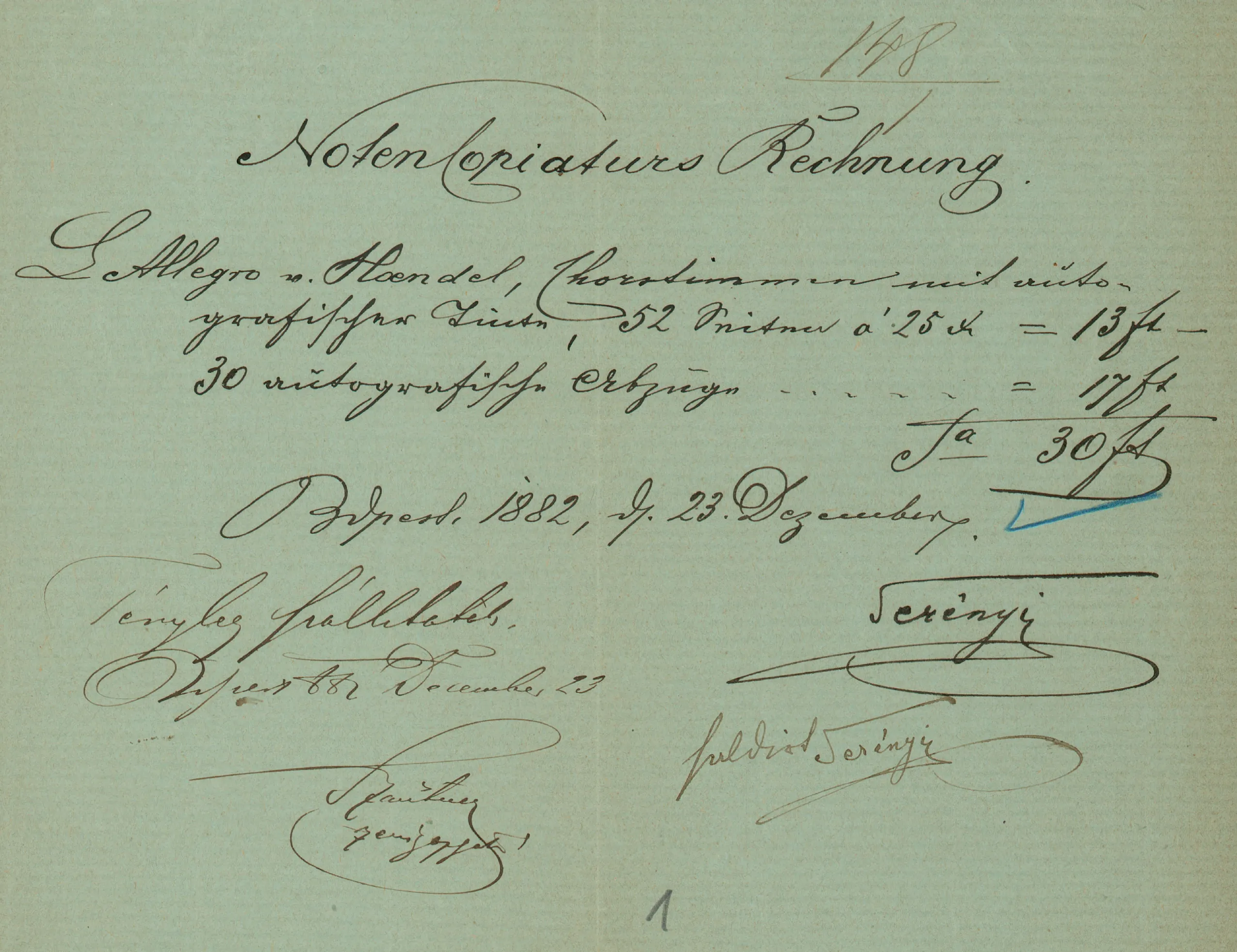

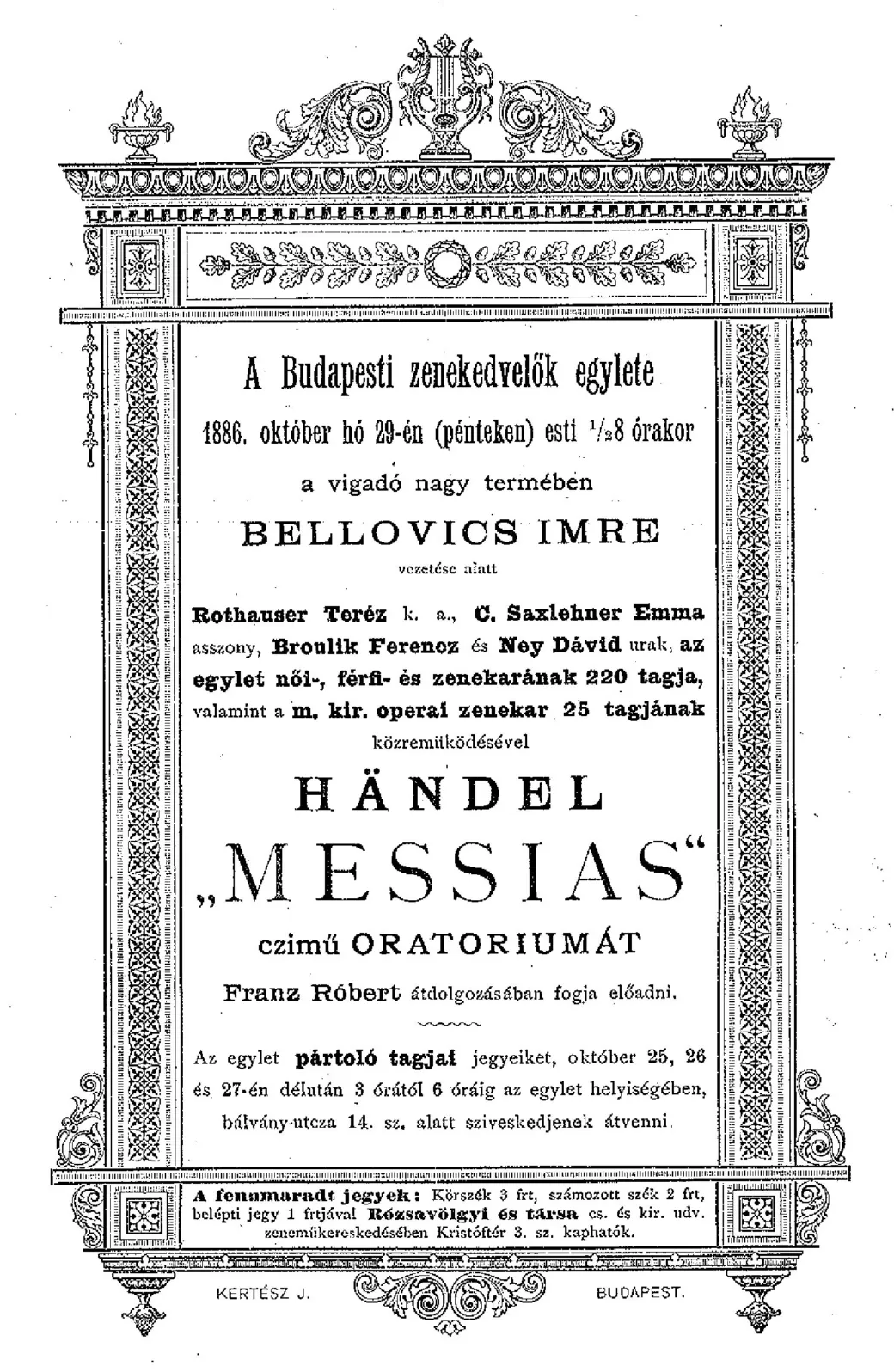

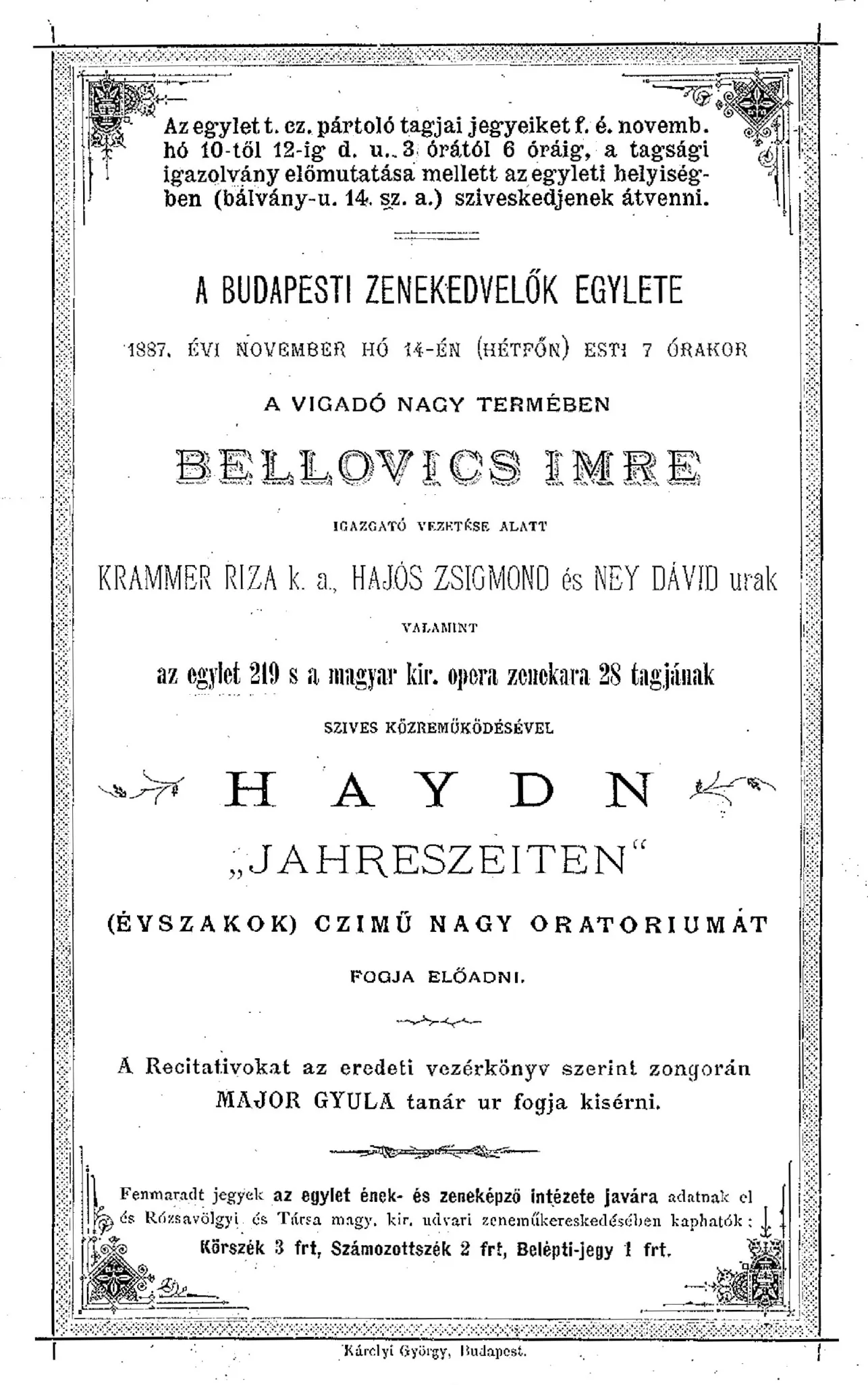

The general development following the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 lead to a more favorable new era, fostering the establishment of civic organizations in Hungary. The second half of the century saw the re-establishment of music societies throughout the country, most notably the Budai Zeneakadémia [Music Academy of Buda] and the Budapesti Zenekedvelők Egyesülete [Music Lovers’ Association of Budapest].

Budapest City Archives, VIII. 613a

Both established in 1867, these institutions were almost exclusively responsible for the organization of the increasingly popular oratorio performances until the beginning of the 20th century.

Fortepan ID 22937

For the members of the Buda Academy of Music, early music was not an entirely unfamiliar domain, as thanks to Liszt’s contribution, the predecessor of the institution, the Church Music Society of Buda, had already dealt with the publications of the St. Cecilia Society of Regensburg, founded by Franz Witt, and particularly the masters of 16th-century vocal polyphony such as Palestrina. The growing enthusiasm for oratorio performances was also fueled by the community experience of the expanding musical ensembles.

BHM Kiscell Museum 54.219.1

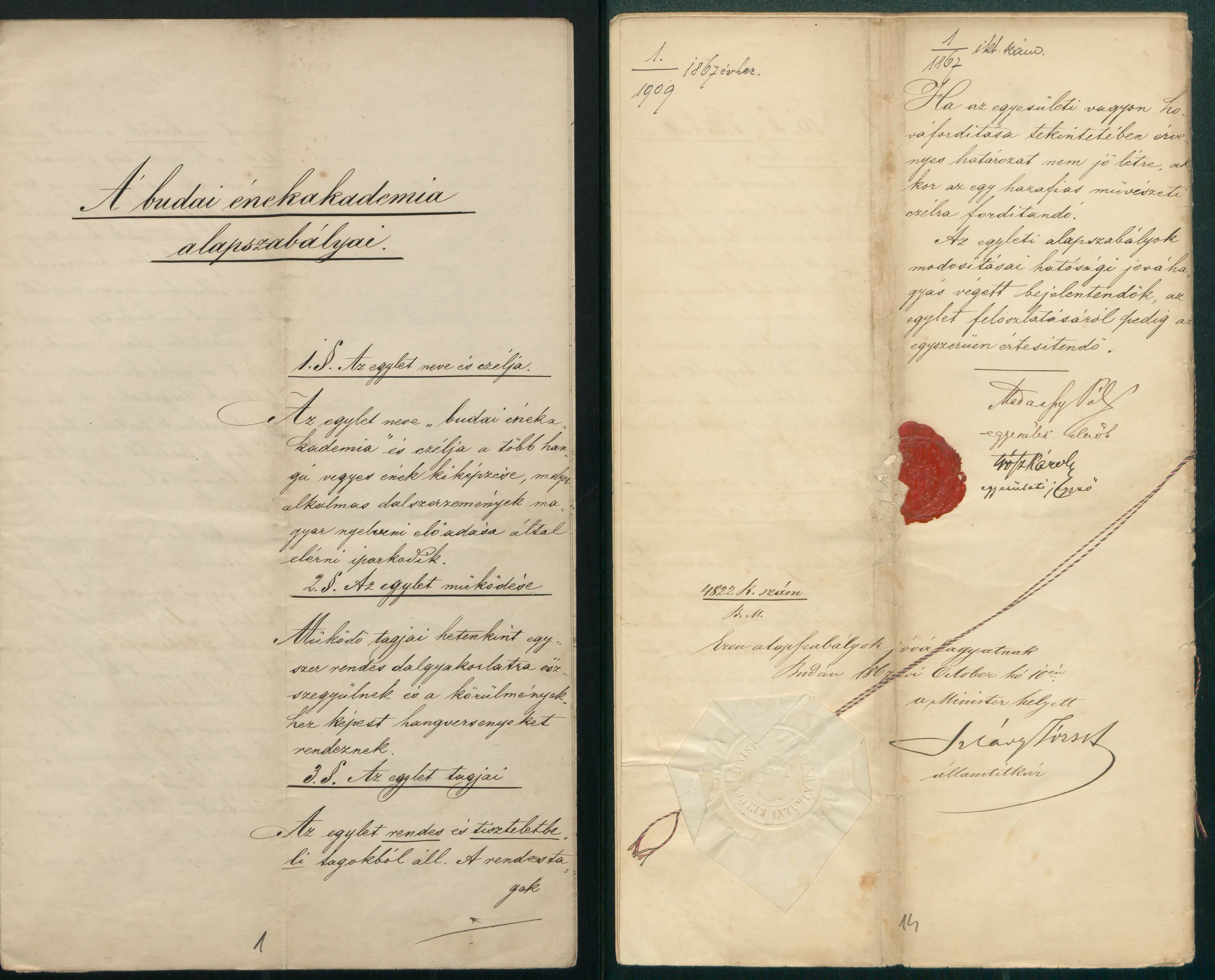

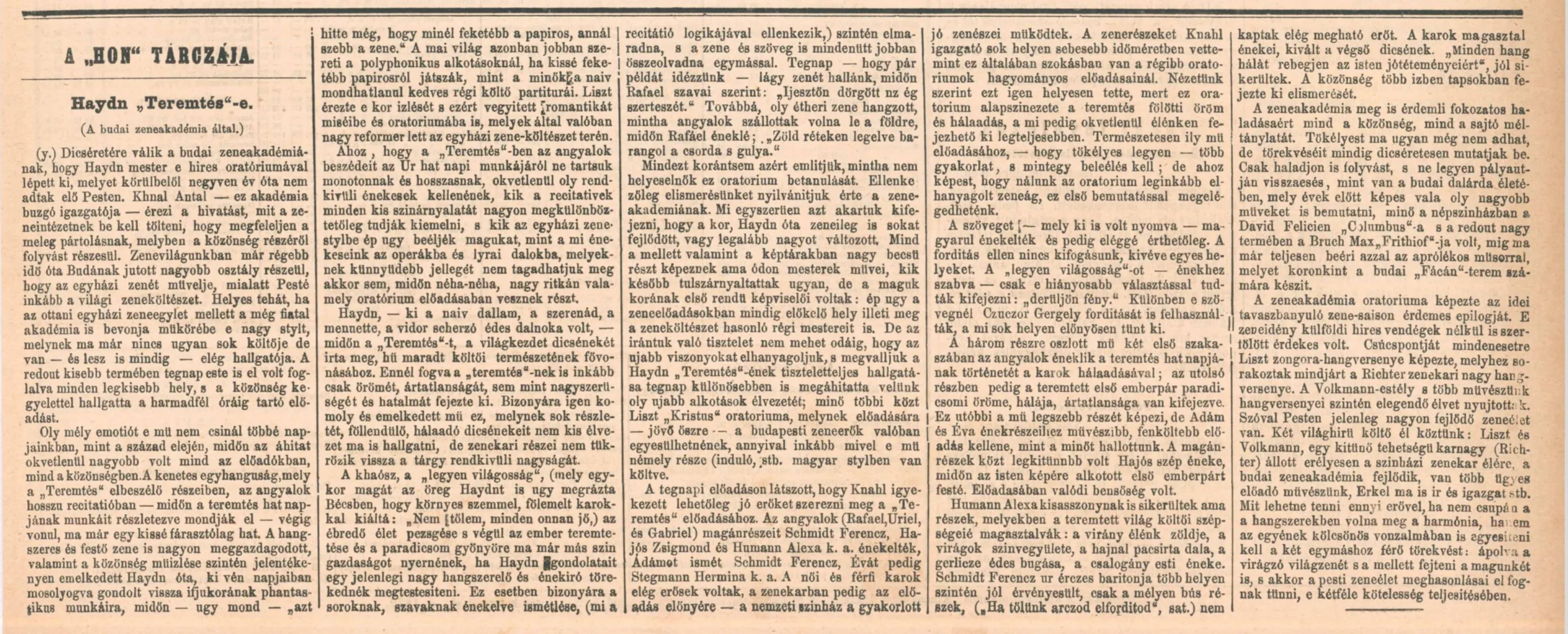

By the end of the century, the repertoire of the new Hungarian music societies included Mendelssohn’s Romantic oratorios, and – next to Handel’s oratorios and Bach’s cantatas – works by Haydn: the latter were considered “ancient music” and were positioned among the works of great masters of the past.

Department for Hungarian Music History of the Institute for Musicology, RCH HUN-REN

Budapest City Archives, VIII. 613a

However, contemporary press reports suggest that, despite the genre’s popularity, Haydn’s works have not always met the public’s expectations – an explanation might be possibly given by evoking the changes in both style and taste that had occurred since these pieces were composed, or because of the subsequent transformations of the oratorio genre.

A Hon, 11 April 1872.

Until the turn of the century, however, the major classical works missing from Hungarian concert life become one of the recurring topoi in the press, sometimes completed with sad references to the abundant programs of the period’s foreign music societies as a model to follow. The interest in the great oratorical compositions of earlier periods does not disappear, and by the end of the century, in addition to the performances of monumental Romantic works, Handel’s large-scale oratorios will be also performed in Hungary, in parallel with the broader European trend.

Department for Hungarian Music History of the Institute for Musicology, RCH HUN-RE

Department for Hungarian Music History of the Institute for Musicology, RCH HUN-RE

Thus, in addition to the foreign examples and the tireless researchers into the past of Hungarian national music, the musical societies and their enthusiastic leaders greatly contributed to the establishment and maintenance of interest into the musical past from the 1870s until the turn of the century, which later served as the basis for the emergence and positive reception of early music performance in Hungary.

Curated by Szabolcs Illés