Sámuel Brassai in the Musical Life of the Capital (1851–1859)

Investigating the scarce decade Brassai, “the last Renaissance Man of Transylvania,” spent in the Hungarian capital through his activity as a music critic as well as his circle of professional and personal friends.

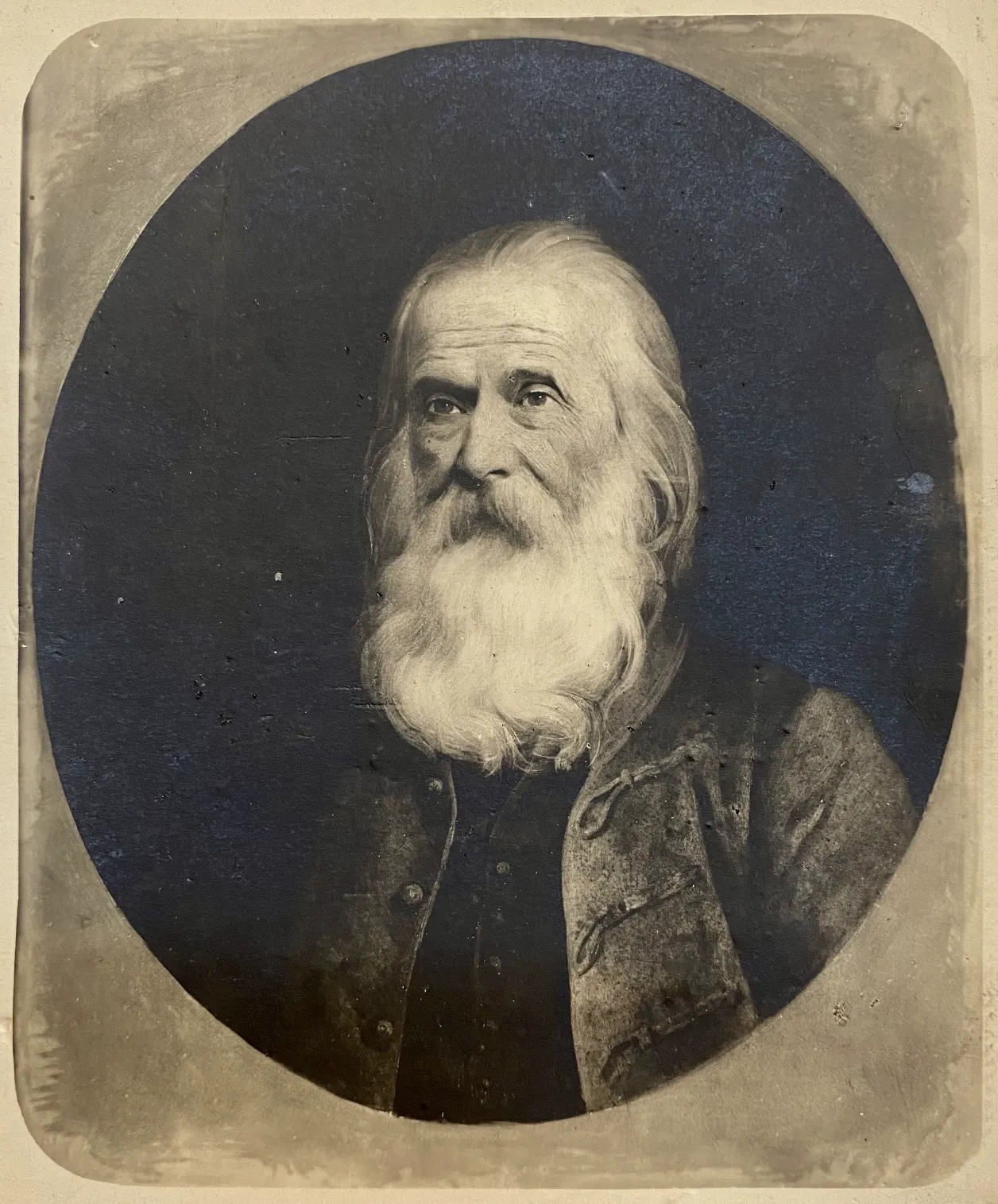

Sámuel Brassai (1797/1800–1897), “the last Renaissance Man of Transylvania,” was a well-known music lover and an all-round musician: a piano teacher, a performer, a music critic, and a genuine music pilgrim, who even willing to travel abroad for the sake of a good performance. Born in Torockószentgyörgy (today: Coltești, Romania), he primarily worked in Kolozsvár (today: Cluj-Napoca, Romania) and its surroundings, but in 1851 he moved to Pest to escape the persecution following the 1848–1849 revolution. He lived in the Hungarian capital for nine years, until 1859,1 where he taught, published, edited journals and listened to a great variety of music – and, as a music critic, he published reviews. He reported on his concert experiences and formulated his concert-chronicle-type criticisms as feuilletons published in newspaper, however, he occasionally wrote on the subject in his personal correspondence as well. Our website presents the music-related writings and extended network of contacts of Brassai’s years in Pest.

Unitarian Transylvanian Archives, Brassai Sámuel Estate, sign. 237.

I. Musical writings of the Pest years

1. Brassai as a music critic

During the years he spent in Pest, Sámuel Brassai was one of the pioneers of the professional music criticism emerging at the time.2 Although his interest in this field had already manifested itself in the Kolozsvár press of the 1830s, there is no doubt that, the rise of his career in music journalism was inspired by the concert life and professional environment he had met in the capital. He published nearly 50 musically themed articles, most of which were opera and concert reviews, or articles on music history (e.g. his feuilleton series on Beethoven).3 His reviews appeared in the journals Szépirodalmi Lapok, Divatcsarnok, Budapesti Hírlap, Pesti Napló, and he signed them by his own name or as Canus.4 The pseudonym might have been chosen because, by then, he was already an esteemed corresponding member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences for nearly a decade and a half. The Latin word Canus (lit. “white, grey, grey-haired”) was perhaps a self-ironic gesture, because it aptly described the distinctive „Uncle Brassai” look, unmistakable for its long grey hair and beard, which had already developed by the early 1850s.

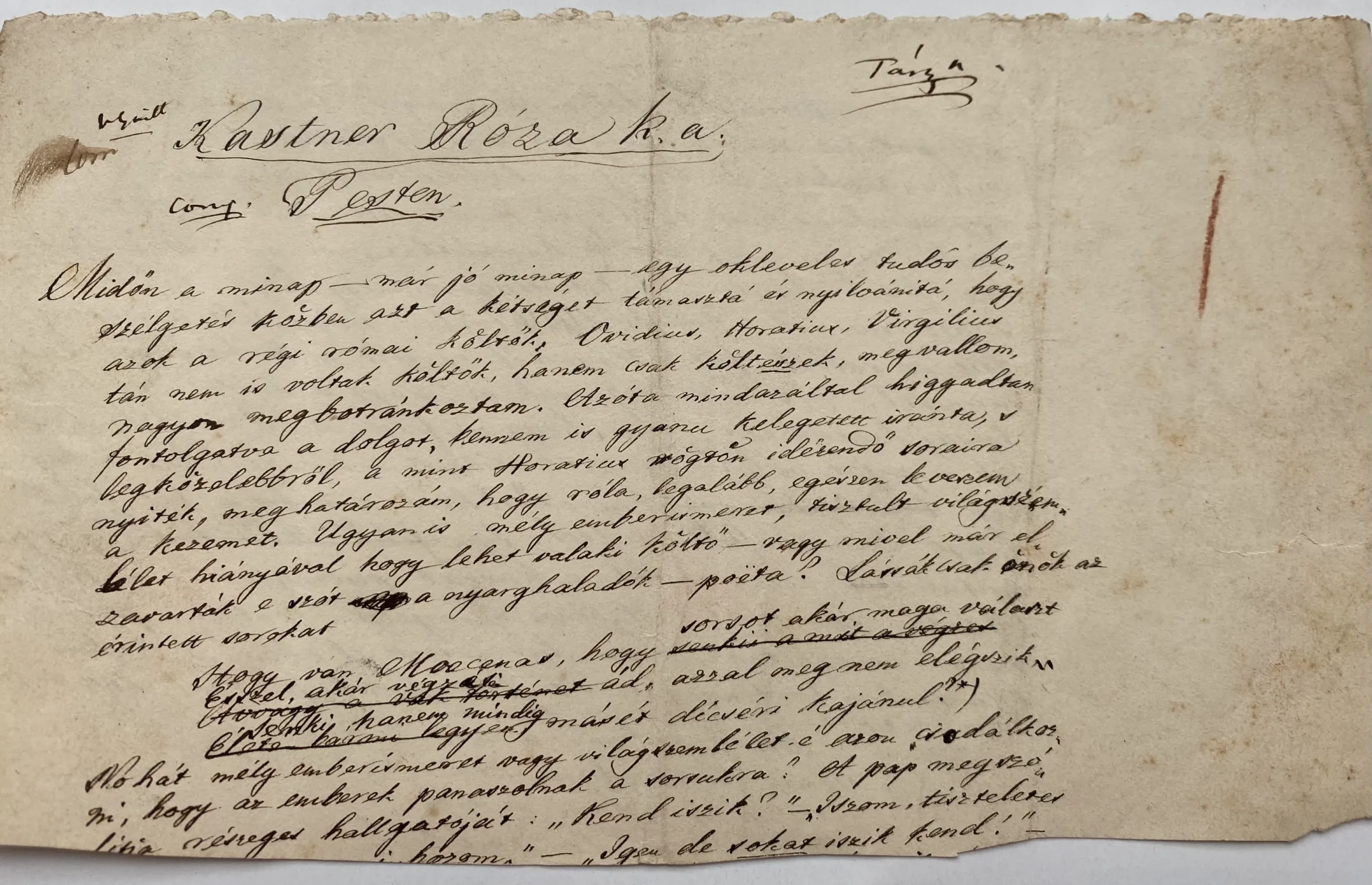

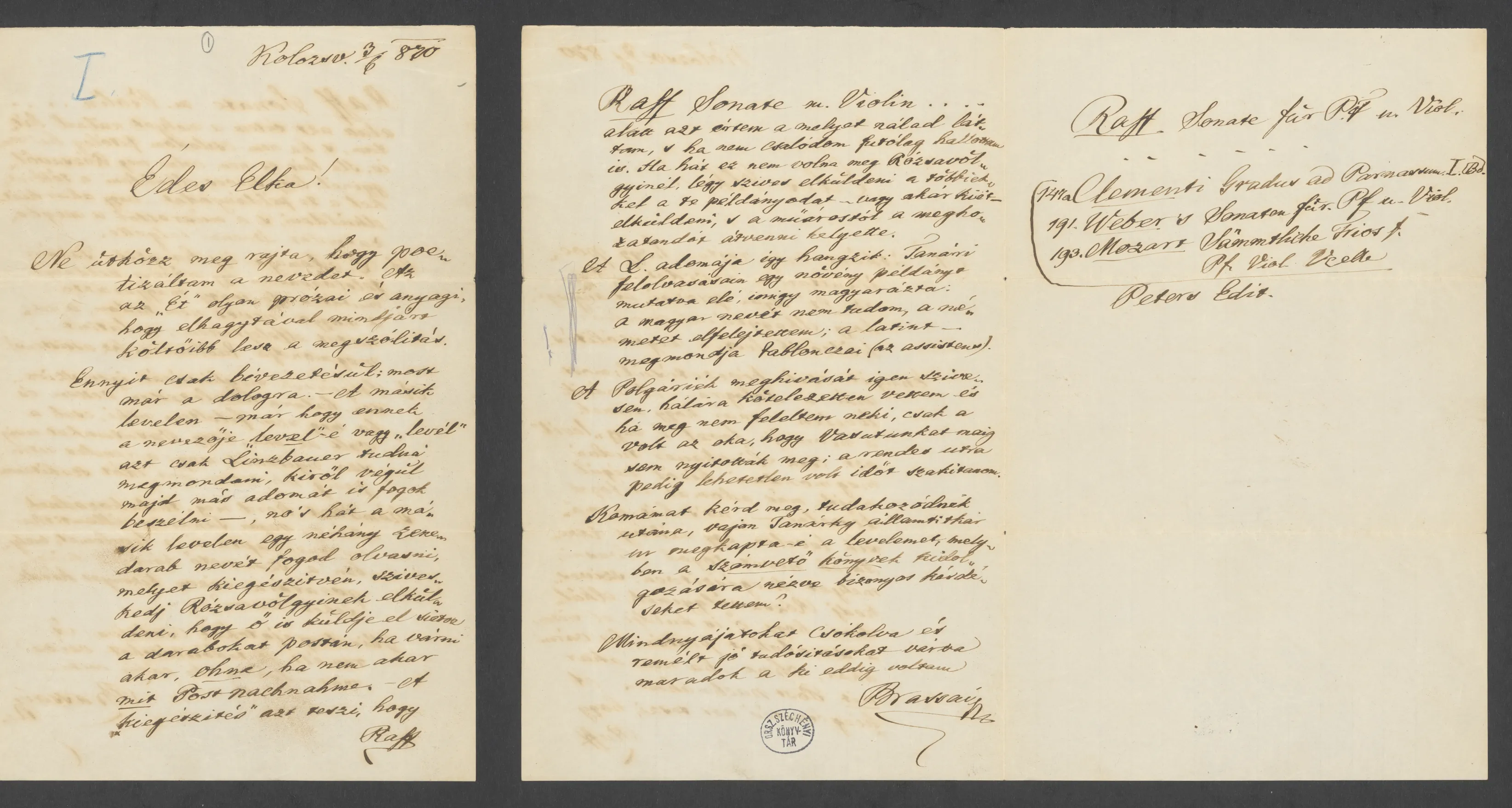

In the course of my recent research, I found a previously unknown manuscript music review by Brassai in his estate preserved at the Unitarian Transylvanian Archives in Kolozsvár. The review concerns a concert given by the Viennese pianist Rosa Kästner in Pest.5 Based on the artist’s series of visits to the Hungarian capital, it was probably written in 1857. The layout of the manuscript gives the impression that Brassai intended the article for the editorial board of a journal. However, it was not actually published; at least I have not been able to find any trace of this artice in the contemporary press.

Unitarian Transylvanian Archives, Brassai Sámuel Estate, sign. 232.

Regarding the manuscript, it is important to mention that two other autograph reviews by Brassai have survived in the archives of Budapest, which have not been mentioned so far in the literature. The one titled “Figaro, Figaro, Fiiiiigaro” is preserved at the Manuscript Collection of the National Széchényi Library, while the review entitled “Rossini Pesten” [Rossini in Pest] can be found at the Petőfi Literary Museum’s Manuscript Department. Both reviews were written in 1858 and reflect on concerts held in Pest, but were published in the journal Delejtű of Temesvár (today: Timișoara, Romania), signed by Canus.6

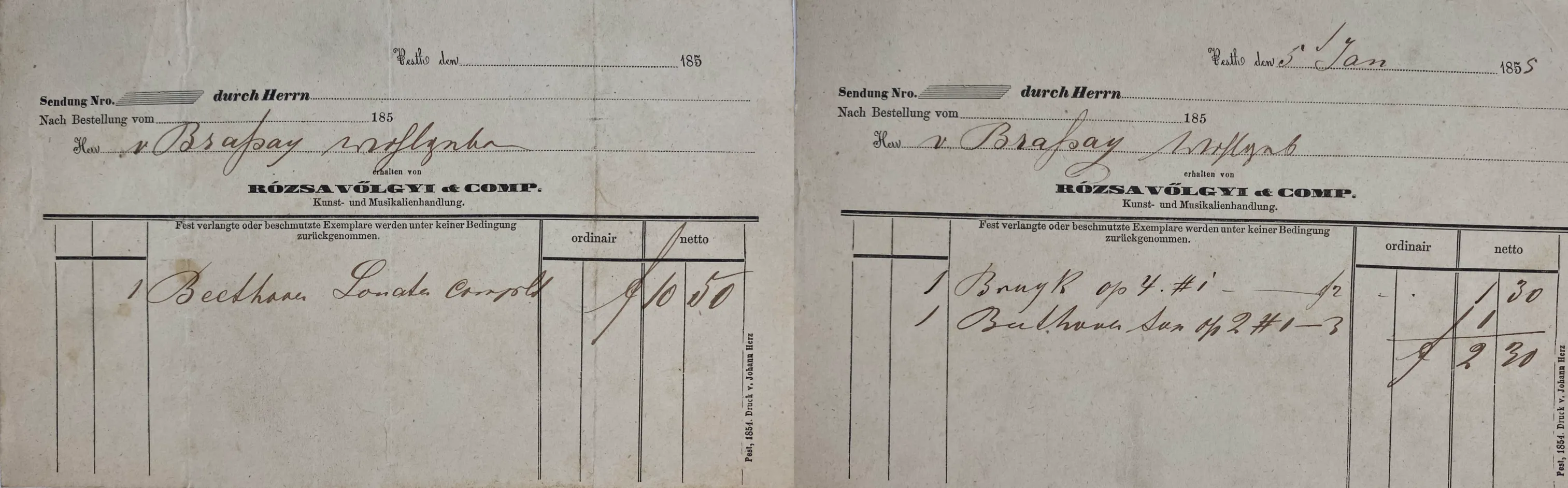

Besides writing reviews, the scholar must have also made music in Pest. He owned a piano, which he had sent home to Kolozsvár after his move in 1859.7 He expanded his music library with great pleasure, as is evidenced by the receipt issued by the publishing company Rózsavölgyi & Co in 1855.

Unitarian Transylvanian Archives, Brassai Sámuel Estate, sign. 190.

2. Editor of the “Criticai Lapok” [Criticai Journal] (Pest, 1855)

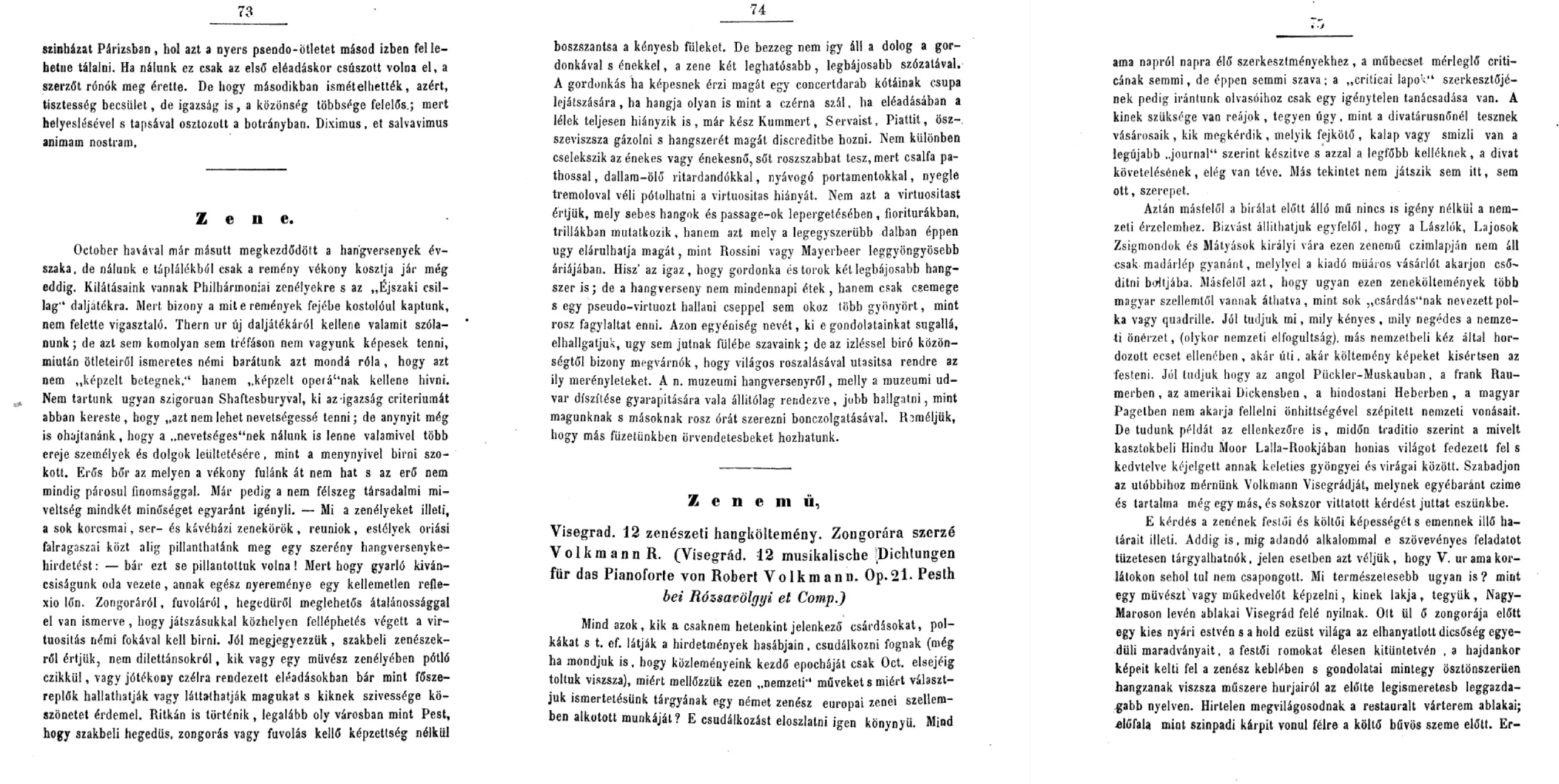

The fourteen years of editorial experience Brassai had gained at the Vasárnapi Újság in Kolozsvár from 1834 to 1848 came in handy during the first year of his stay in Pest, as he continued this kind activity. In 1851, he launched the youth magazine Fiatalság Barátja [The Friend of Youth], of which one volume (6 booklets) was published, and in 1855 he founded Criticai lapok [Journal on Criticism], hoping that – due to increasing popularity of music criticism – a newly launched specialized newspaper would be well received. He had a better chance of publishing such a journal in Pest than in Kolozsvár, because in Pest there was a higher demand for it as early as the beginning of the 1830s. A journal edited by József Bajza with the same title – albeit with different spelling: Kritikai Lapok – was released between 1830 and 1836. However, Brassai’s critical review saw only one published issue, containing seven chapters, of which two were dedicated to music: V. Zene [Music] and VI. Zenemű [Musical Composition].8

Library of Musicology of the Institute for Musicology, RCH HUN-REN, Major Estate, Ma 4093.

3. Brassai’s polemic with Ferenc Liszt

Des Bohémiens et de leur musique en Hongrie [On Gypsies and Their Music in Hungary], Ferenc Liszt’s 1859 volume claiming that the music played by Gypsy bands was not of Hungarian but of Gypsy origin caused public outcry in Hungary. The most thorough attempt to refute this claim from the Hungarian side came from Sámuel Brassai, Magyar- vagy Czigány-zene. Elmefuttatás Liszt Ferenc “Czigányokról” írt könyve felett [Hungarian or Gypsy music. Reflection on Ferenc Liszt’s book on the Gypsies (Kolozsvár, Stein, 1860).9 Even though Brassai still lived in Kolozsvár at that time, the capital’s press was waiting for his intervention related to Liszt’s book; obviously, because he was already considered an influential figure of the Pest music criticism, too.10

![Sámuel Brassai’s reaction to Ferenc Liszt’s Des Bohémiens et de leur musique en Hongrie [On Gypsies and Their Music in Hungary] (Paris, Librairie Nouvelle, 1859): Magyar- vagy Czigány-zene. Elmefuttatás Liszt Ferenc “Czigányokról” írt könyve felett [Hungarian or Gypsy music. Reflection on Ferenc Liszt’s book on the Gypsies (Kolozsvár, Stein, 1860). Library of Musicology of the Institute for Musicology, RCH HUN-REN, 21.836.](/images/4-cigany-konyv.webp)

Library of Musicology of the Institute for Musicology, RCH HUN-REN, 21.836.

II. Brassai’s Position in Pest – His Musical Network of Connections

1. Brassai and Ferenc Erkel

The roots of their friendship can be traced back to the years the young Erkel spent in Kolozsvár (cca. 1828–1834). During this period the later creator of the Hungarian national opera and “the last Transylvanian polymath” were both still active in similar areas. Erkel worked as piano tutor for József Csáky, while Brassai, barely ten years his senior, did the same at the Bethlen family.

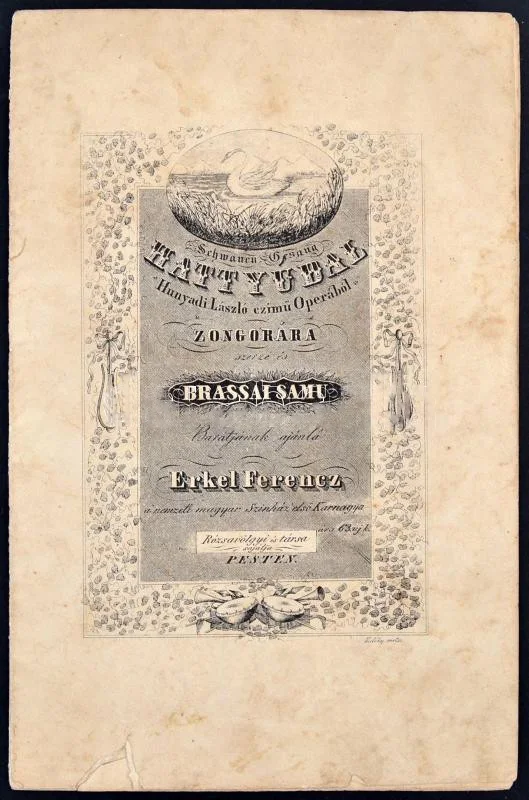

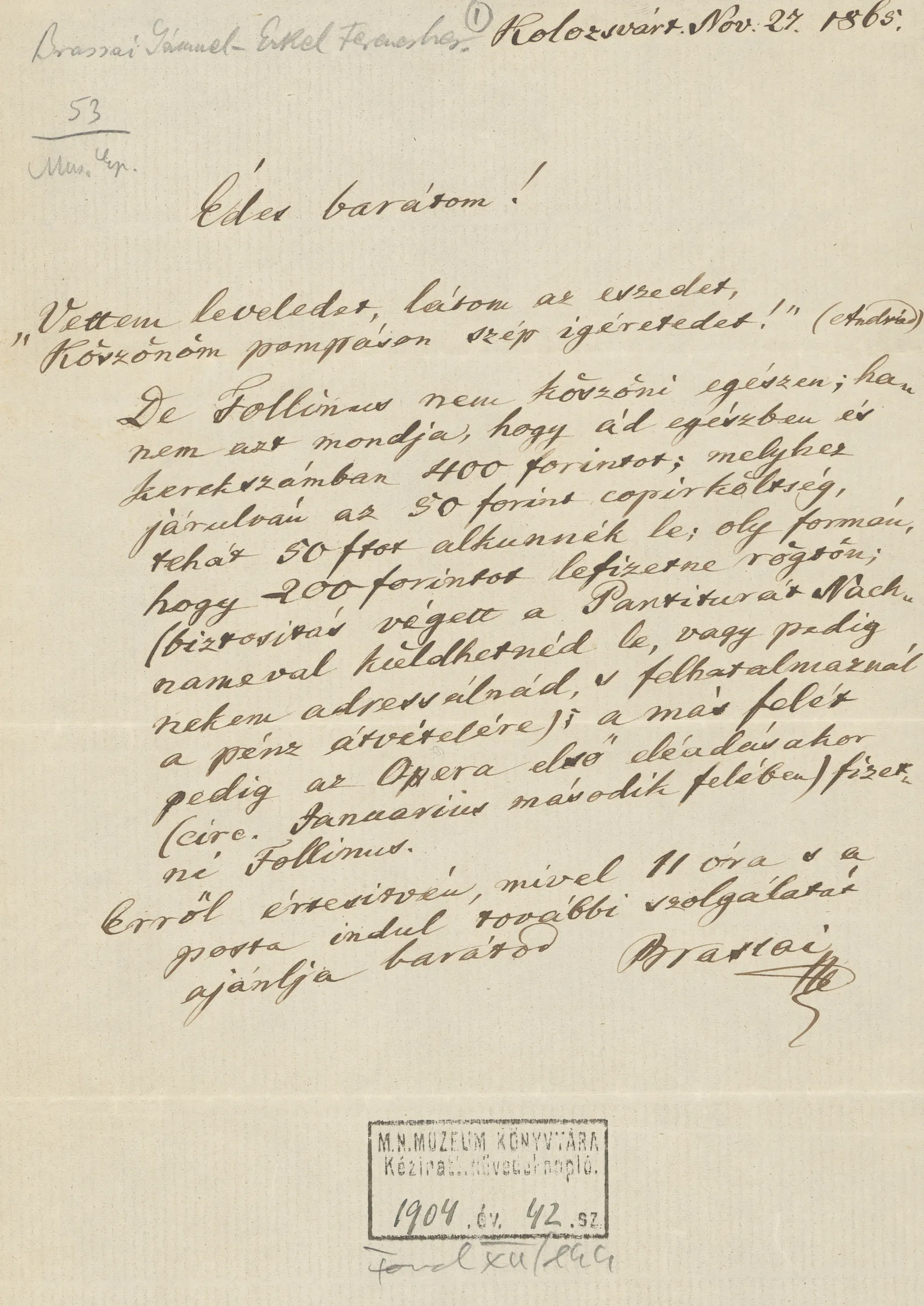

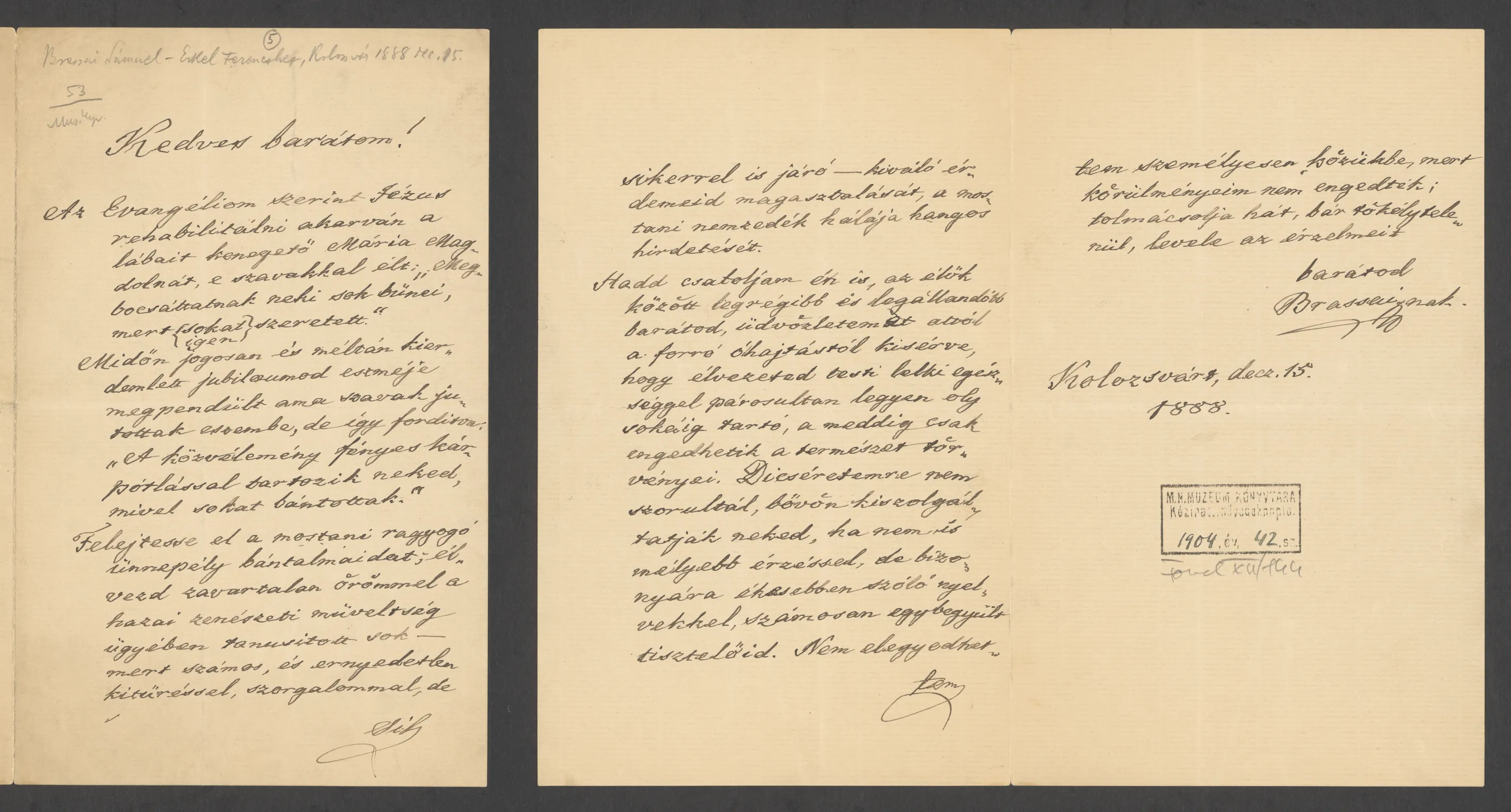

In 1843, Erkel dedicated his Hattyúdal [Swan Song] from the opera Hunyadi László for piano (1843) to his friend he mentioned with the nickname “Samu Brassai.” Before the Kolozsvár premiere of the opera Bánk bán, Erkel corresponded with Brassai about sending the score to János Follinus, the director of the Kolozsvár National Theatre (from this correspondence, only Brassai’s letter survive).11 Brassai’s letter congratulating Erkel on his 50th anniversary as a conductor (1888) is an often-quoted and eloquent relic of their friendship.

Library of Musicology of the Institute for Musicology, RCH HUN-REN, Major Estate, Ma 603.276. 603.276.

National Széchényi Library, Manuscript Collection, sign. Fond XII/144.

National Széchényi Library, Manuscript Collection, sign. Fond XII/144.

National Széchényi Library, Manuscript Collection, sign. Fond XII/144.

2. Brassai and the Gönczy family

During his years in Pest (from 1852) until his return to Kolozsvár (1859), Brassai taught mathematics and physics at Pál Gönczy’s private boarding school.12 As a music connoisseur and supporter of women’s music education, Brassai found talented young students in the capital, as well, including Etelka Gönczy (1851–1937), the daughter of the private school’s director. He taught her how to play the piano. Brassai maintained a close friendship with the Gönczy family for the rest of his life, often visiting them in Pest and Karácsond. His friendship with Etelka was based on their shared musical interests, as they often played four-hand piano together, and the elderly scholar also accompanied her to concerts in Pest.13

National Széchényi Library, Manuscript Collection, sign. Levelestár 3938.

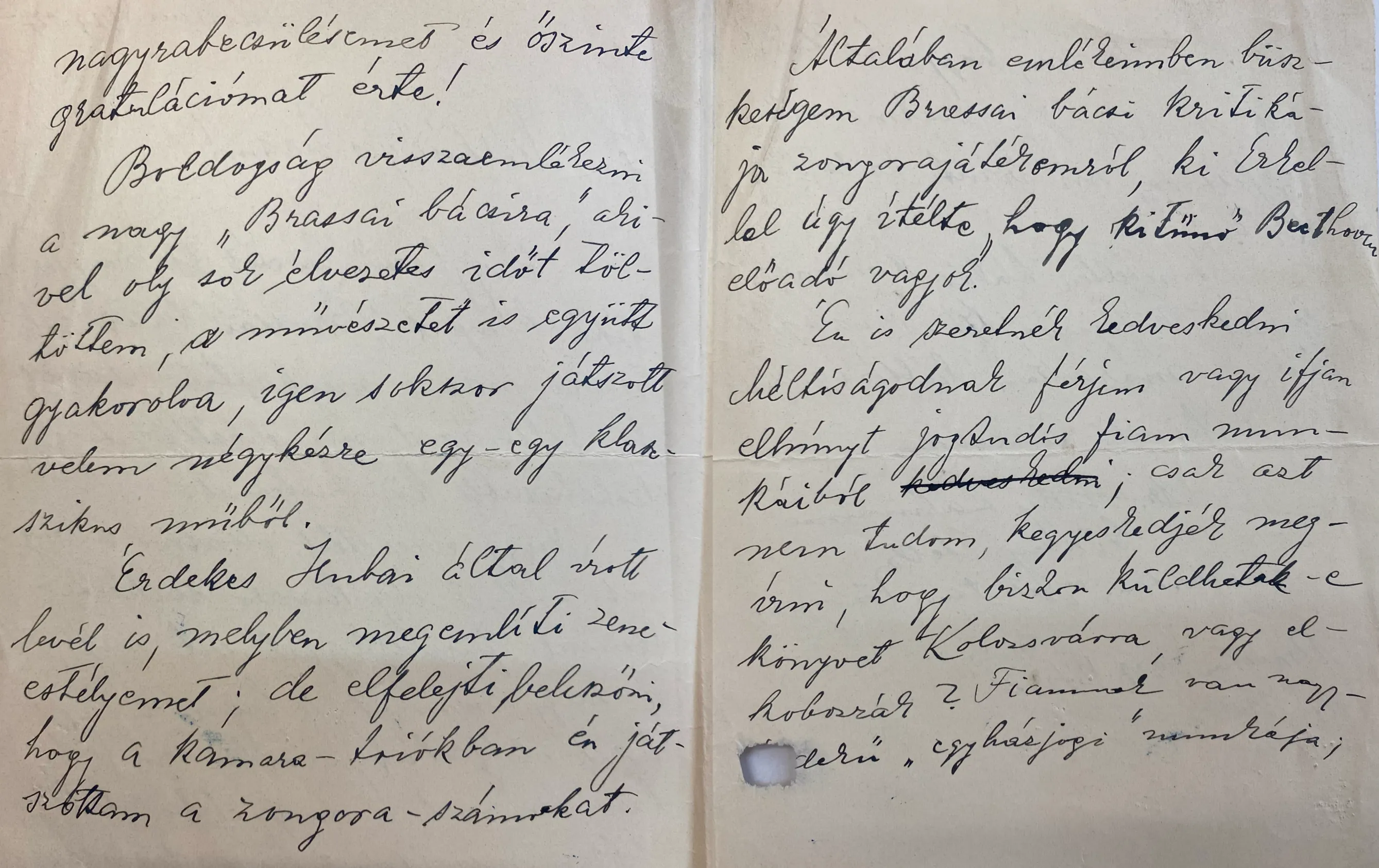

In a late letter to Brassai’s monographer György Boros, Etelka recalls the experience of playing chamber music with “Uncle Brassai” and the memory of her career as a soloist that began with Brassai and Ferenc Erkel’s positive judgement of her playing:

It is a pleasure to remember the great “Uncle Brassai” with whom I spent so much quality time together cultivating the art of four-hand piano playing. In general, I remember that I was very proud of his opinion of my piano playing: together with Erkel, he considered me an excellent Beethoven interpreter.14

Unitarian Transylvanian Archives, György Boros Estate, sign 758.

The same letter also sheds light on Pál Gönczy’s artistic and literary salon,15 probably also frequented by Brassai and Erkel, and which has not been previously covered in music historical literature.

3. Sámuel Brassai and István Bartalus

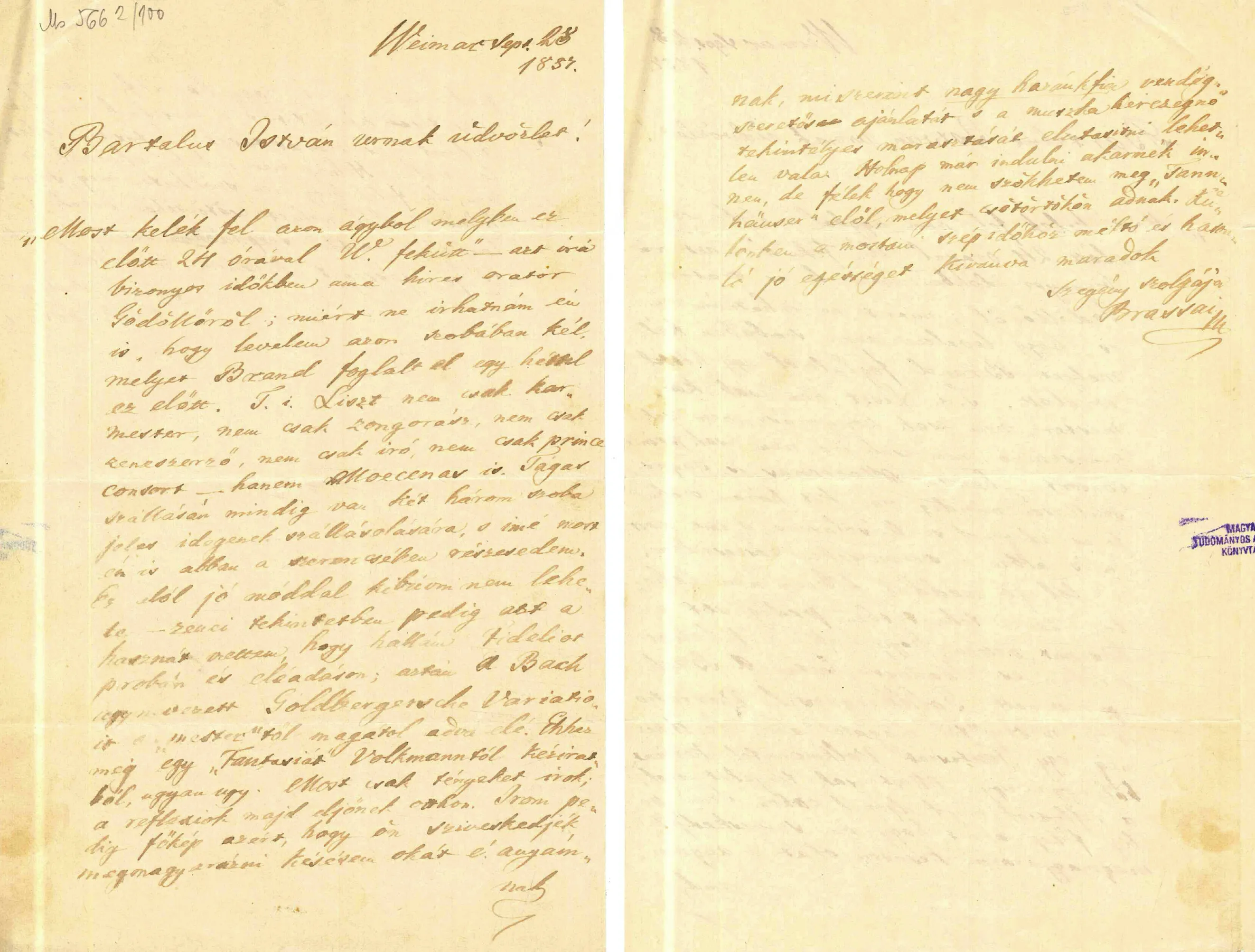

Folk music researcher and music historian István Bartalus moved from Kolozsvár to Pest in 1851, just as Brassai; from 1852, both of them taught at Pál Gönczy’s private boarding school.16 Their frequent correspondence, having both a personal and a professional character reflects a sincere friendship.

In his letter to Bartalus, written during his stay in Weimar in 1857,17 Brassai enthusiastically announces that he has been given a room in the residence of Ferenc Liszt, the very room that “Brand” [i.e. composer Mihály Mosonyi] occupied the week before. In this letter, the scholar shows his respect and humility towards Liszt by not only calling him a conductor, pianist, composer, writer and prince concert, but also a Maecenas.

It is important to note that the document also records a concert experience that was essential during Brassai’s travels. In Weimar, he listened to works by Beethoven, Bach, and Volkmann:

In musical terms, I have had the benefit of hearing Fidelio in rehearsal, and the Goldbergishe Variations performed by the Master himself... I also heard a Fantasia by Volkmann played from the manuscript, in the same way.18

Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Department of Manuscripts & Rare Books, Ms 5662/100.

4. Brassai and Kornél Ábrányi Snr.

Kornél Ábrányi Snr., historian of 19th-century Hungarian music, had a professional connection to Brassai. There are no sources confirming their direct friendship, and their correspondence has not survived. Ábrányi’s works, however, give us reason to believe in the reality of their repeated meetings and discussions. On Brassai’s death (24 June, 1897), Ábrányi published an obituary in Budapesti Hírlap [Budapest Journal], titled “Néhai Brassai bácsi mint zenész” [The late Uncle Brassai as a musician], an authentic musical tribute to the memory of the polyhistor, coming from an external source. Transylvanian press was proud to re-published excerpts of this article, which can also be read as Chapter XIV of the of the volume Képek a múlt és jelenből [Images from the Past and Present].19

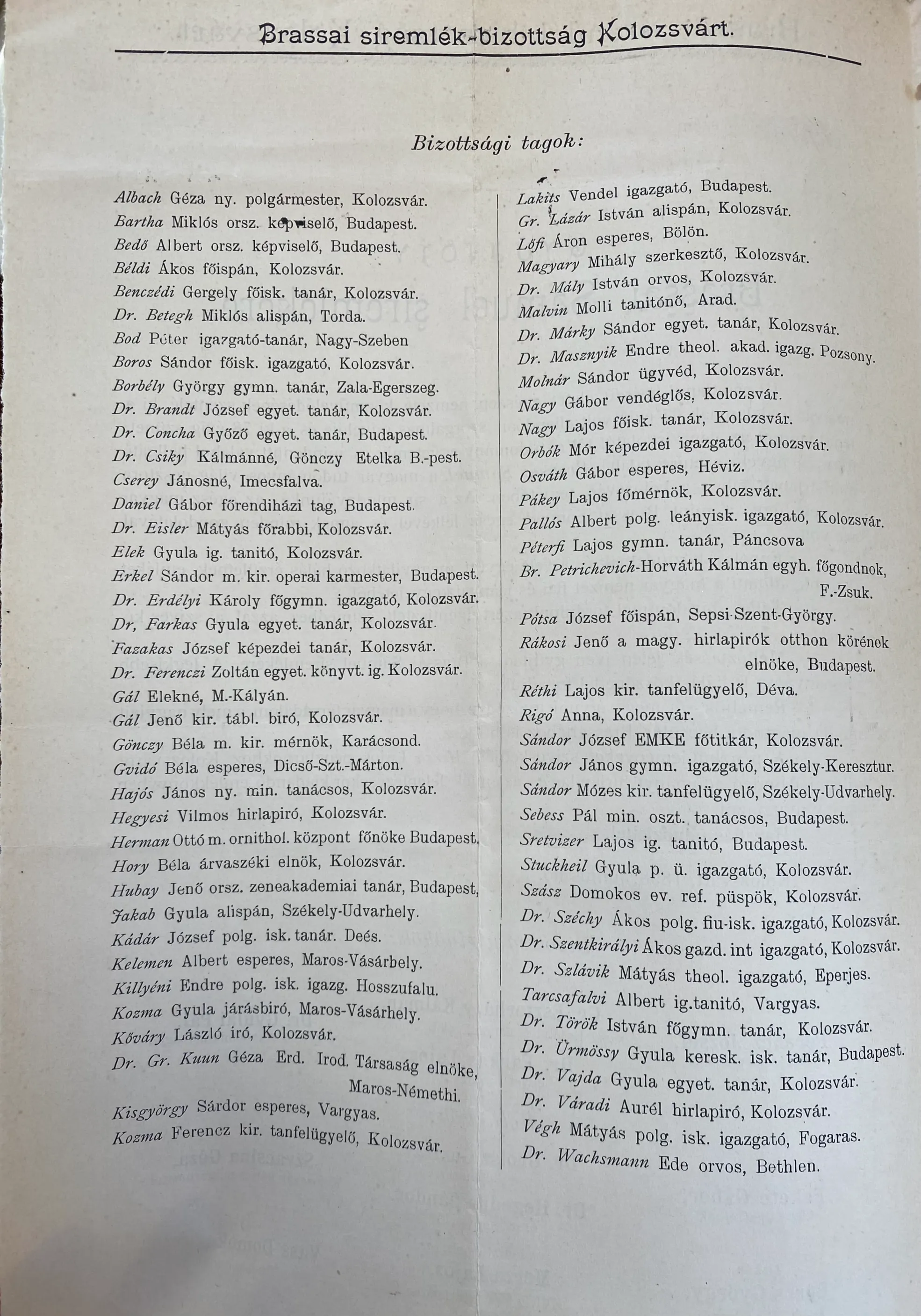

Sámuel Brassai had multiple ties to the music life of the capital. After his return to Kolozsvár (1859), he continued to visit the concert halls of Budapest and enjoyed the hospitality of his close friends. On his death, a Brassai Memorial Committee was set up; it is fascinating to take a last look at its members, as a testimony to the scholar’s deep-rooted connections with Pest. Among the members, we find opera conductor Sándor Erkel, Ferenc Erkel’s son; violinist and Music Academy teacher Jenő Hubay, and also the dear friend, student, and chamber music partner Etelka Gönczy, the wife of Kálmán Csiky.

Unitarian Transylvanian Archives, Brassai Sámuel Estate, 186.

Curated by Beáta Simény

1 Brassai, Sámuel: „A XI. Axioma”. Akadémiai Értesítő 9/9 (1898), 415–426, here: 416.

2 Kornél Ábrányi Snr., mentions Sámuel Brassai among the initiators of Hungarian professional writing on music, together with István Bartalus, Mihály Mosonyi, Gusztáv Szénfy, Gábor Egressy, and Ábrányi Snr. himself. Cf. id. Ábrányi, Kornél: Erkel Ferenc élete és működése [Ferenc Erkel’s life and activity] (Budapest, Schunda, 1895), 93.

3 Cf. Brassai: „III. Beethoven”, Divatcsarnok 2/19–21 (1854).

4 For the season beginning on 1853, Canus was the music critic of Szépirodalmi Lapok [Literary Newspaper] with regularly published reviews. Cf. Simény Beáta: „Brassai Sámuel, a Szépirodalmi Lapok zenekritikusa” [Sámuel Brassai – Music Critic of the Review Szépirodalmi Lapok] In: Kim, Katalin; Horváth, Pál (ed.): Budapesti mindennapok Erkel és Liszt korában: Ünnepi konferencia Eckhardt Mária tiszteletére [Everyday Life in Budapest in the Age of Erkel and Liszt] (Budapest, HUN-REN Bölcsészettudományi Kutatóközpont, Zenetudományi Intézet, 2023), 179–202, here: 186–189.

5 For more details about Róza Kästner’s 1857 performances in Pest, see: Békéssy, Lili Veronika: Zenei mindennapok és zenei reprezentáció Pest-Budán. A Főváros zeneisajtója 1857-ben. [Musical everyday life and representation in Pest-Buda. The musical press of the capital in 1857] PhD Thesis (Budapest, Liszt Academy of Music, 2023).

6 Cf. Canus [Sámuel Brassai]: „Rossini Pesten”, Delejtű, 1/10 (7 September 1858), 82–84; Canus [Sámuel Brassai]: „Figaro, Figaro, Fiiiii....garo!”, Delejtű, 1/14 (5 November 1858), 113–116.

7 He asked his friend and colleague István Bartalus to have his piano tuned and sent to Kolozsvár. Cf. Sámuel Brassai’s letter to István Bartalus, 2 April 1860. Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Department of Manuscripts & Rare Books, Ms 5662/102.

8 For more detail on the journal Criticai Lapok see: Tímea Berki: “Brassai Sámuel kritika-értelmezései az 1850-1860-as években. Egy példa: Criticai Lapok” [Samuel Brassai’s interpretations of criticism in the 1850s and 1860s. An example: Criticai Lapok], Keresztény Magvető 3 (2007), 277–287.

9 On the volume and its publication, see the review by Adrienne Kaczmarczyk: “Liszt Ferenc: A cigányokról és magyar zenéjükről. Fordította Hamburger Klára” [Ferenc Liszt: On Gypsies and their Hungarian Music. Translated by Klára Hamburger] (Budapest: Balassi Kiadó, 2020)”, Liszt Magyar Szemmel, 2021/46, 8–11.

10 Cf. Hölgyfutár (20 October 1859), 10/125, 1024.

11 Sámuel Brassai’s letter to Ferenc Erkel (Kolozsvár, 27 November 1865), National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, sign. Fond XII/144.

12 According to György Boros, all teachers at the institute were prosecuted patriots, like Brassai. Cf. Boros, György: Dr. Brassai Sámuel élete [The life of Dr. Sámuel Brassai] (Kolozsvár, Minerva Irodalmi és Nyomdai Műintézet Részvénytársaság, 1927), 159.

13 In 1872, Imre Székely dedicated his 21st Hungarian Fantasy to Etelka, but her career as a pianist came to an end following her marriage to Kálmán Csíky. Cf. Kéry, János: Székely Imre (1823–1887) életrajza, magyar ábrándjai és műveinek jegyzéke [Imre Székely’s biography, his Hungarian Fantasies, and the catalogue of his works]. DLA Thesis (Budapest, Liszt Academy of Music, 2015), 105.

14 The Hungarian original: “Boldogság visszaemlékezni a nagy ‘Brassai bácsira,’ akivel oly sok élvezetes időt töltöttem, a művészetet is együtt gyakorolva, igen sokszor játszott velem négykézre egy-egy klasszikus műből. Általában emlékeimben büszkeségem Brassai bácsi kritikája zongorajátékomról, ki Erkellel úgy ítélte, hogy kitűnő Beethoven-előadó vagyok.”

15 Klára Gráber Bősze: „Gönczy Pálné és Csíky Kálmánné Gönczy Etelka – Anya és leánya a nőnevelésért” [Mrs Pál Gönczy and Mrs Kálmán Csíky, née Etelka Gönczy – A mother and a daughter for the education of women], Könyv és Nevelés 2018/1, 106.

16 Katalin Szőnyi Szerző: “Arany János »koszorús« zenész barátja, Bartalus István,” [János Arany’s “musician laureate” friend, István Bartalus], Parlando 2017/2, 2.

17 Brassai's notebook suggests that his visit to Weimar was one of the last stops on a longer Western European tour of Cf. Unitarian Transylvanian Archives, Brassai Sámuel Estate, sign. 240.

18 The Hungarian original: “Zenei tekintetben azt a hasznát vettem, hogy hallám Fidelót próbán, és a Goldbergishe Variatiot is magától a mestertől adva elé... Ehhez még egy „Fantasia Volkmanntól” kéziratból, ugyan ugy.”

19 Ábrányi, Kornél Sr.: Képek a múlt és jelenből [Images from the Past and Present] (Budapest, Pallas, 1899), 81–87.