Music, Liszt, Poetry

The Everyday Life of Emil Ponori Thewrewk

Emil Ponori Thewrewk (1838–1917), native of Bratislava, was among the first in Hungary to base classical philology research on scientific methodologies. Ponori Thewrewk spent his childhood in his hometown, then he continued his studies in the Piarist Gymnasium in Pest, followed by courses abroad, in Graz, Vienna, Berlin and Leipzig. Upon his return to the Hungarian capital, he founded on the German model the Budapesti Philológiai Társaság (‘Budapest Philological Society’) and was co-editor of the Egyetemes Philologiai Közlöny (‘Universal Philological Journal’).1

Although he had an extensive network of foreign contacts, his teaching and scientific work tied him to Budapest. Except for his youth, he lived in the Buda Castle District.

He also wrote cultural history press articles about the capital.2 However, the true motivation of this enthusiasm was not urban planning.

I have never loved any city as much as Pest; but do not think that it is because of its landscape or buildings, but rather because of some of its inhabitants. After having written prose poems elsewhere, here I face the sprouting of my emotions, which warmed my heart and set my heart’s songs flowing. On this shore stands Józsa, and therefore let no one be surprised that every sinking foam reflects her image.3

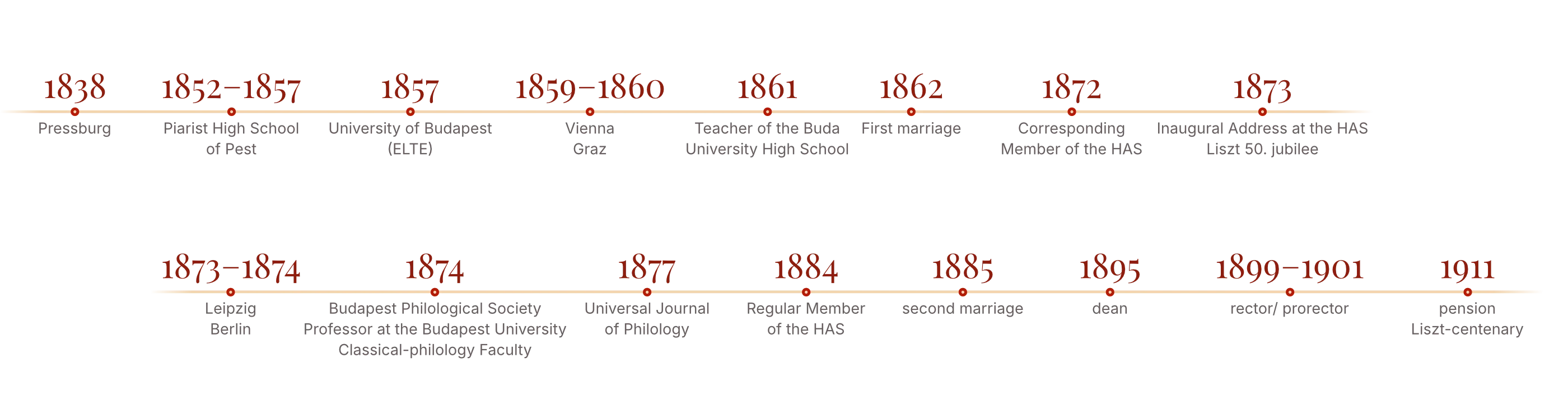

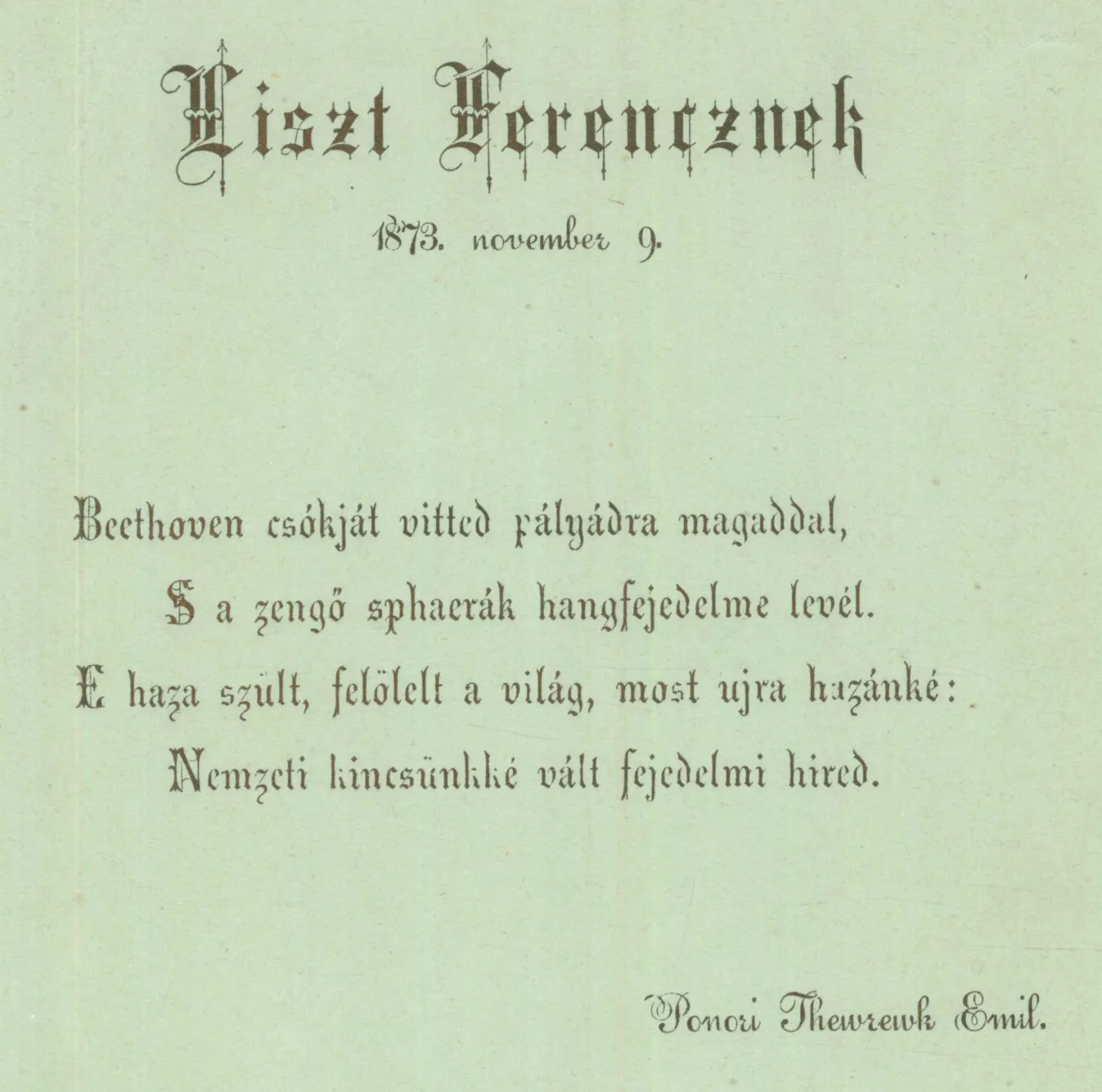

While the safe “harbor” of his private life was his first wife, Josephine Matlekovits, nicknamed Miss Józsa (1841–1864), on the “shore” of his musical writings stood the figure and oeuvre of Ferenc Liszt (1811–1886). In fact, Emil Ponori Thewrewk read out his inaugural address at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences entitled A magyar zene rhythmusa (‘The Rhythm of Hungarian Music’) in 1873, the year of the official unification of Pest-Buda-Óbuda and Ferenc Liszt’s 50th artistic jubilee. A similar occasion framed the celebration of Ponori Thewrewk’s 13 years activity as a high school teacher (1861–1874) and 37 years as a university teacher (1874–1911), i.e. half a century of teaching; namely, this coincided with the 1911 Liszt centenary.

National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Arckép 1253

According to the latest research, classical philologist Emil Ponori Thewrewk sang under the baton of Ferenc Liszt, corresponded with him, and even met him several times.4 Although the original plan was for Ponori Thewrewk to give Hungarian language lessons to the composer, this failed because they could not arrange a suitable time. However, Ponori Thewrewk admired Ferenc Liszt until his death. This admiration was most sincerely expressed in his poems.

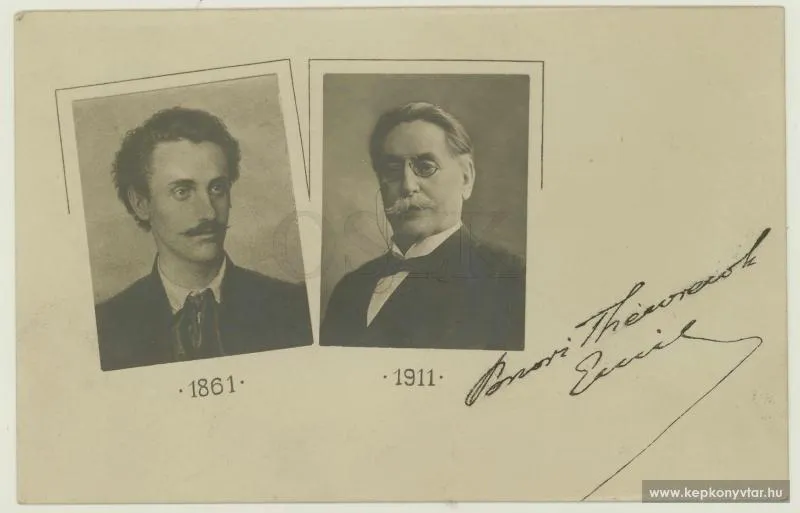

National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Quart Hung 2526/1, 16r

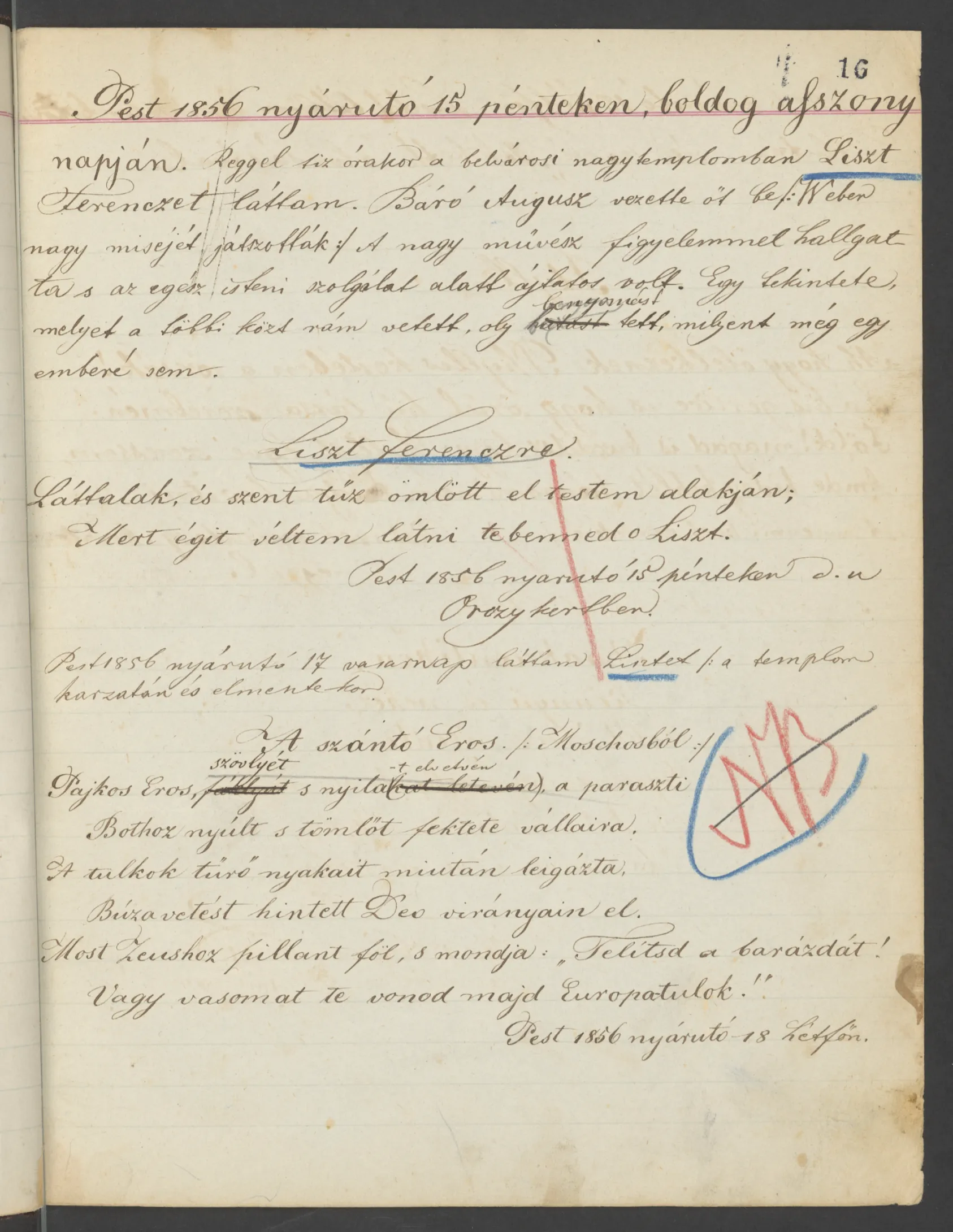

These verses were inspired by the composer's figure and his gaze on Emil Ponori Thewrewk, whom Ponori Thewrewk saw at the mass of the Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary (commonly known as the Inner City Parish Church) on 15 August 1856. It was never published in print, and is preserved only in Ponori Thewrewk’s diary from his youth. In contrast, the epigram written at request for the 1873 jubilee of Ferenc Liszt, was published by numerous press magazines and journals.5 Kornél Ábrányi Sr. even had the four-verses long epigram scattered from the gallery of the National Theatre during the performance of Csikós (‘Horse keeper’) by Ede Szigligeti (play staged on 10 November 1873, in honor of Liszt).6

HAS LIC Department of Manuscripts & Rare Books, Ms 6503/183

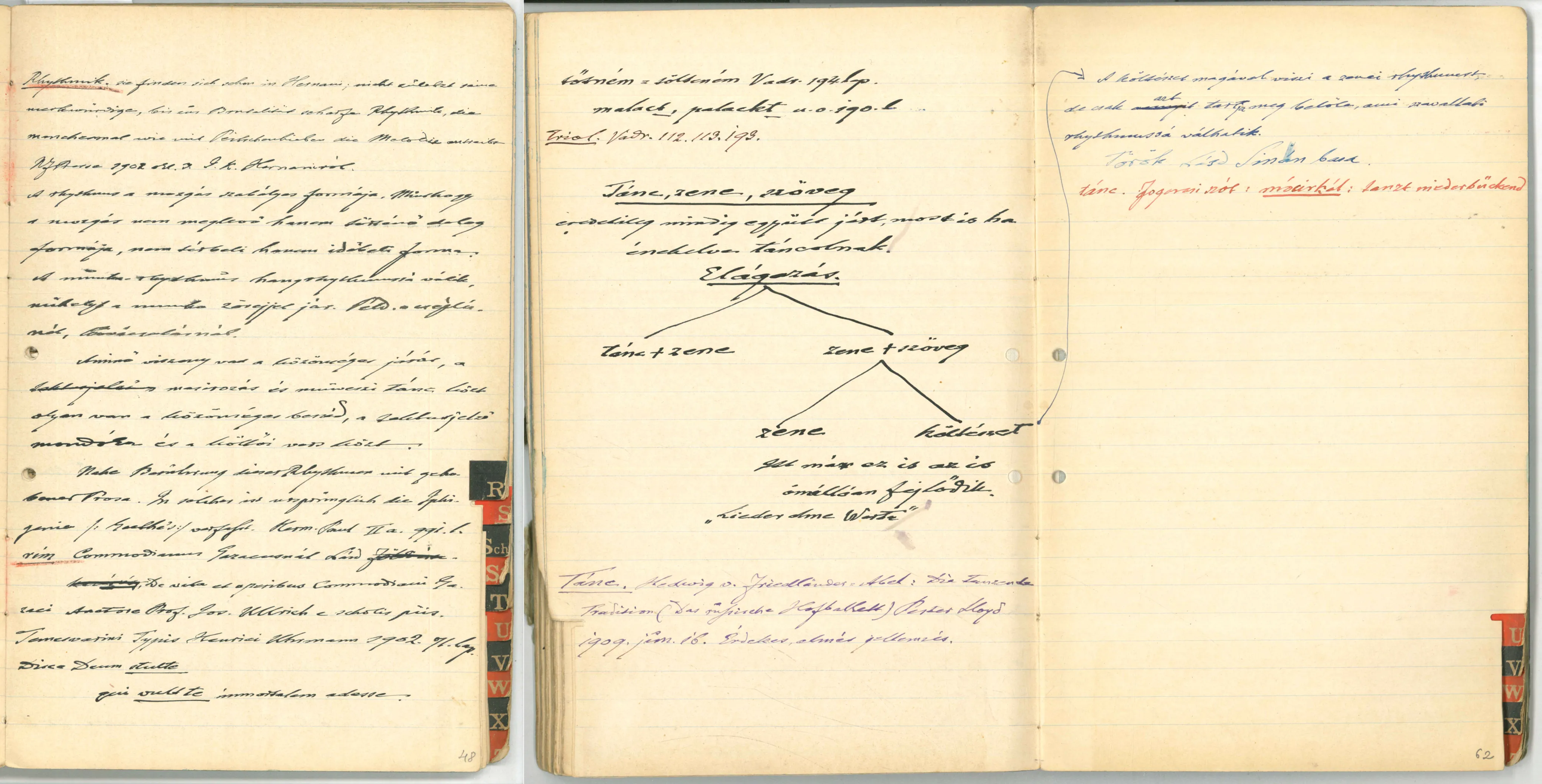

As Emil Ponori Thewrewk himself told, he entered into the world of music by searching for the laws of poetry.7 As a classical philologist, by profession, he was primarily interested in problems related to rhythm, in research examining the relationship between music and language. He even kept a separate notebook for this purpose.

HAS LIC Department of Manuscripts & Rare Books, Ms 6503/181

The hypothesis of these research, following ancient Greek theories, is that the rhythm of speech can be equaled with the rhythm of music. As a result, Ponori Thewrewk refuted Ferenc Liszt’s theory regarding the Gypsy origin of Hungarian music (Liszt’s theory provoked intense debates at the time).8 Since the stress in the Gypsy language is at the end of the word, unlike in Hungarian, where it falls on the first syllable, any analogy or correspondence between the two is incorrect, and therefore their music cannot show any common features. Ponori Thewrewk expanded this thesis in his A hang mint műanyag (‘The Sound as Source of Composition’, 1866) essay as well as in his inaugural address at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences entitled A magyar zene rhythmusa (‘The Rhythm of Hungarian Music’, 1873).

HAS LIC Department of Manuscripts & Rare Books, Ms 315/134

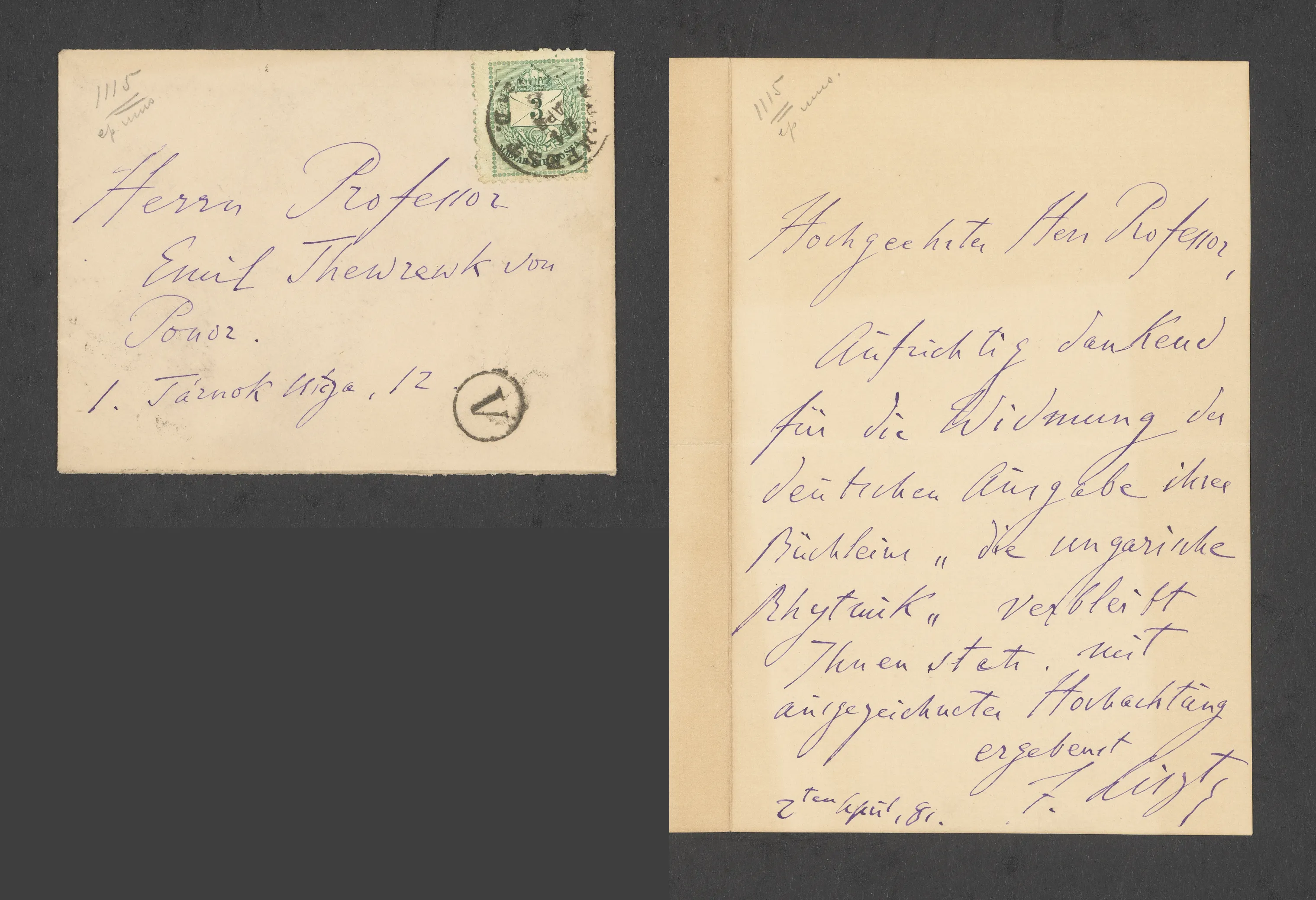

Ferenc Liszt was aware of the content of A magyar zene rhythmusa (‘The Rhythm of Hungarian Music’) and thanked Ponori Thewrewk in a letter for a copy of and dedication of the German edition.

National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Fond XII/673

It is unknown, whether a German edition was actually published. Only one copy of the second, revised Hungarian edition (1881) has survived in Liszt’s library, which Ponori Thewrewk dedicated to the Magyar Zeneművelők Társasága (‘Hungarian Musician’s Society’).9 The printing cost of “The Rhythm of Hungarian Music (2nd edition) was 95 forints 32 penny.”10

Liszt Ferenc Memorial Museum, Liszt’s heritage, LK 236 (originally K 537 (LH))

Unlike Liszt, Emil Ponori Thewrewk was also familiar with the Gypsy language. In 1886, together with József Budenz (1836–1892) and at the request of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Ponori Thewrewk reviewed the manuscript of Czigány nyelvtan (‘Gypsy Grammar’) by Archduke Joseph (Joseph Karl Ludwig 1833–1905).11

Library of Musicology of the Institute for Musicology, RCH HUN-REN, Ma 2465

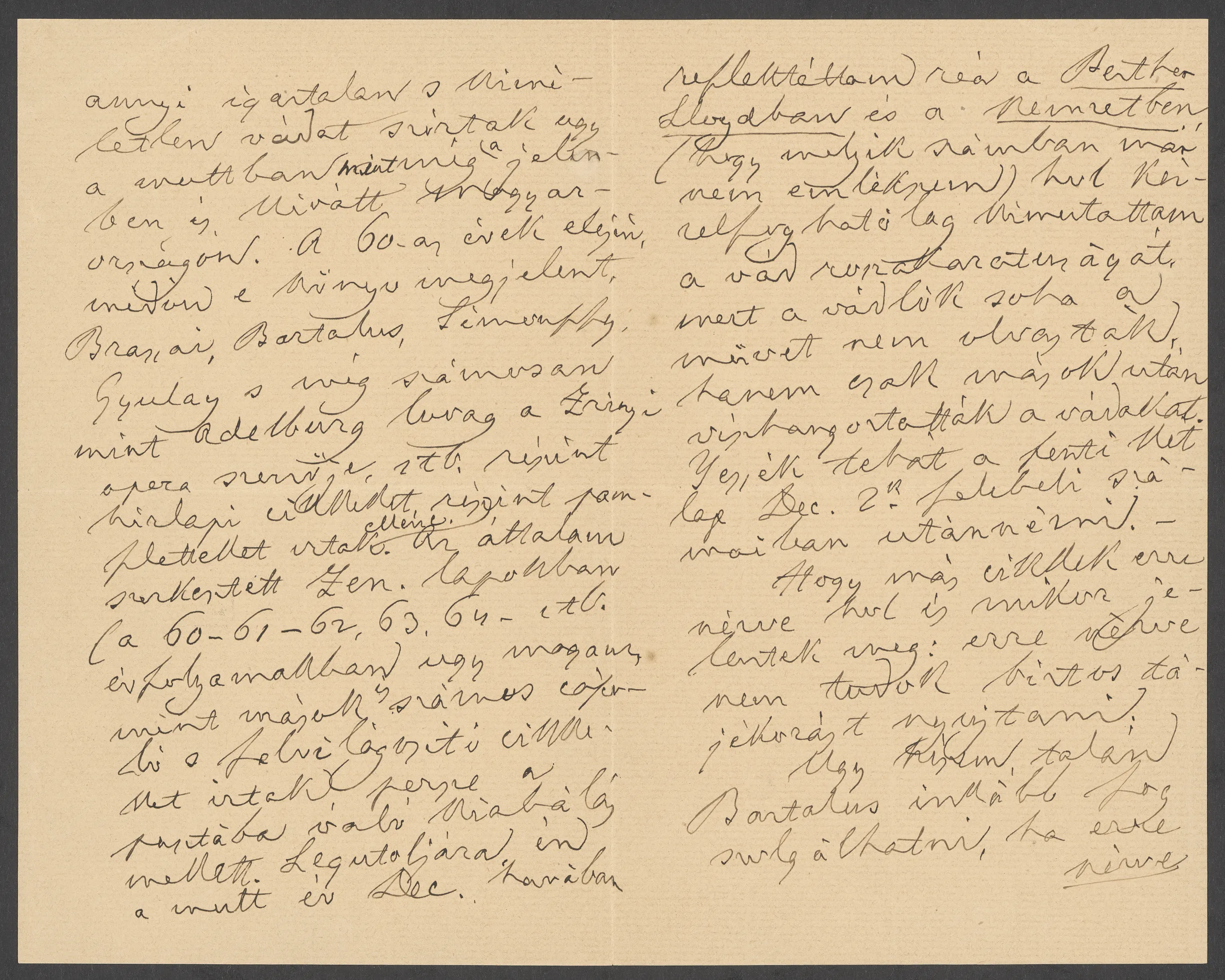

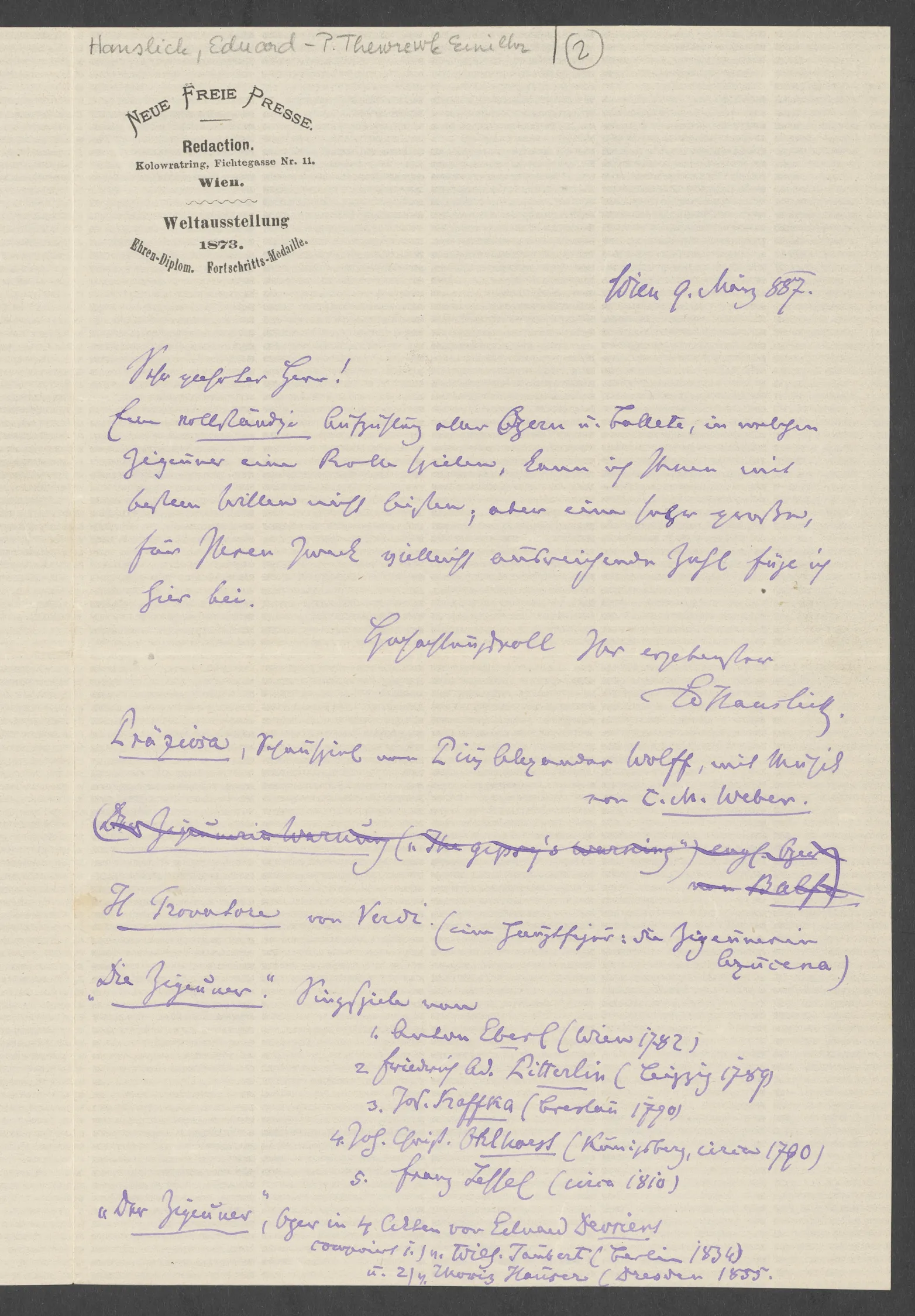

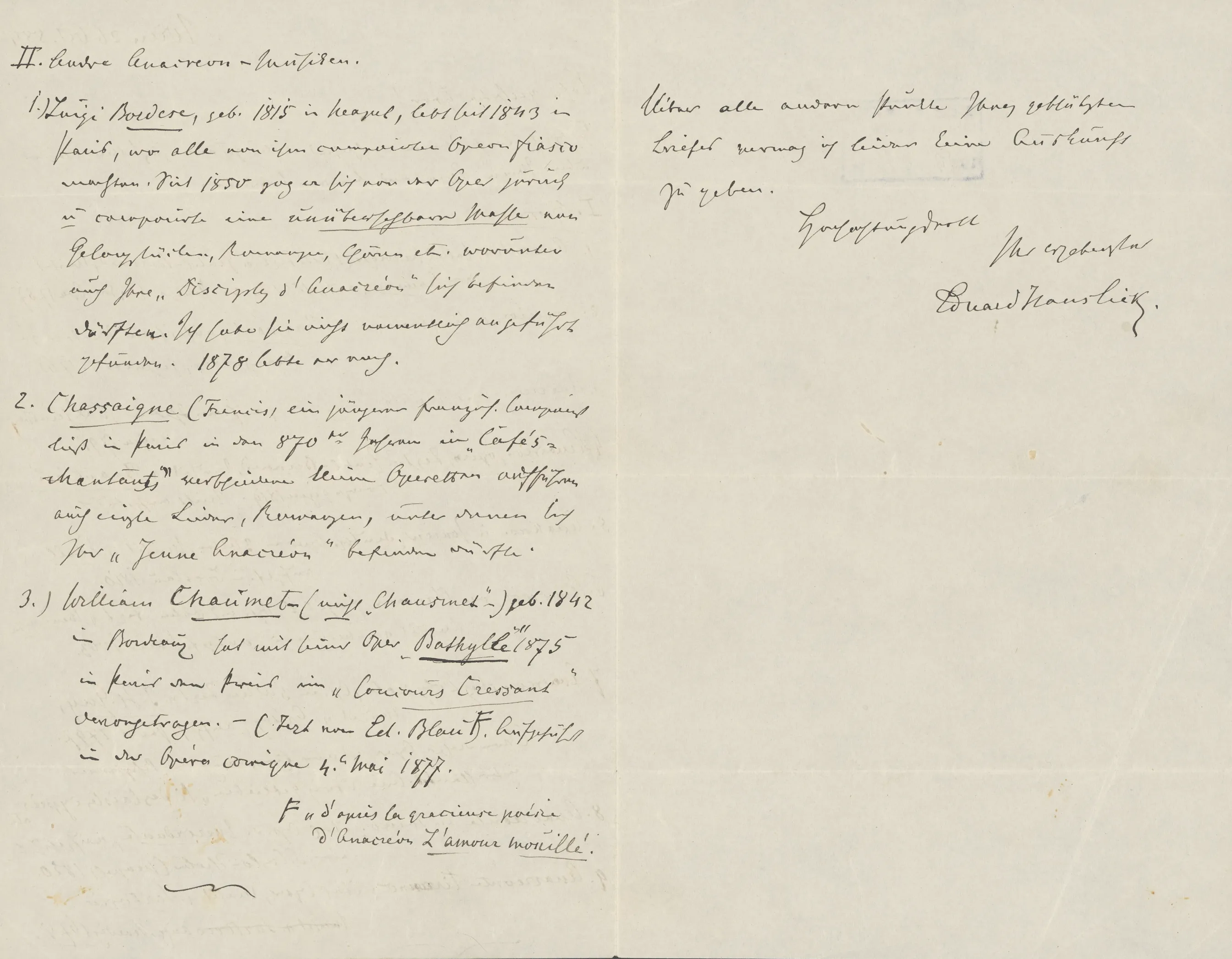

Ponori Thewrewk, with his precision and broad interest, attached a voluminous Irodalmi Kalauz (‘Literary Guide’) to the book, which accounts for almost half of it. In it, he published a detailed bibliography of Roma cultural history research and listed the literary, visual and musical works that depict and/or are inspired by it. For the latter purpose, and “instead of a long search”,12 he contacted two renowned music critics of the time: the Wagner fan Kornél Ábrányi Sr. and the anti-Wagnerian Eduard Hanslick.

National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Levelestar 176

In Kornél Ábrányi Sr., in “the distinguished specialist”, about whom “I thought that as a music teacher and writer he would know more about the literature related to Liszt’s work [“gypsy book”] than I did. I was greatly disappointed.”13 However, Ponori Thewrewk was impressed by Hanslick’s list of operas based on gypsy topics.

National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Levelestar 10743

The following list appeared in the Hungarian edition of the book (1888):14

Library of Musicology of the Institute for Musicology, RCH HUN-REN, Ma 2465

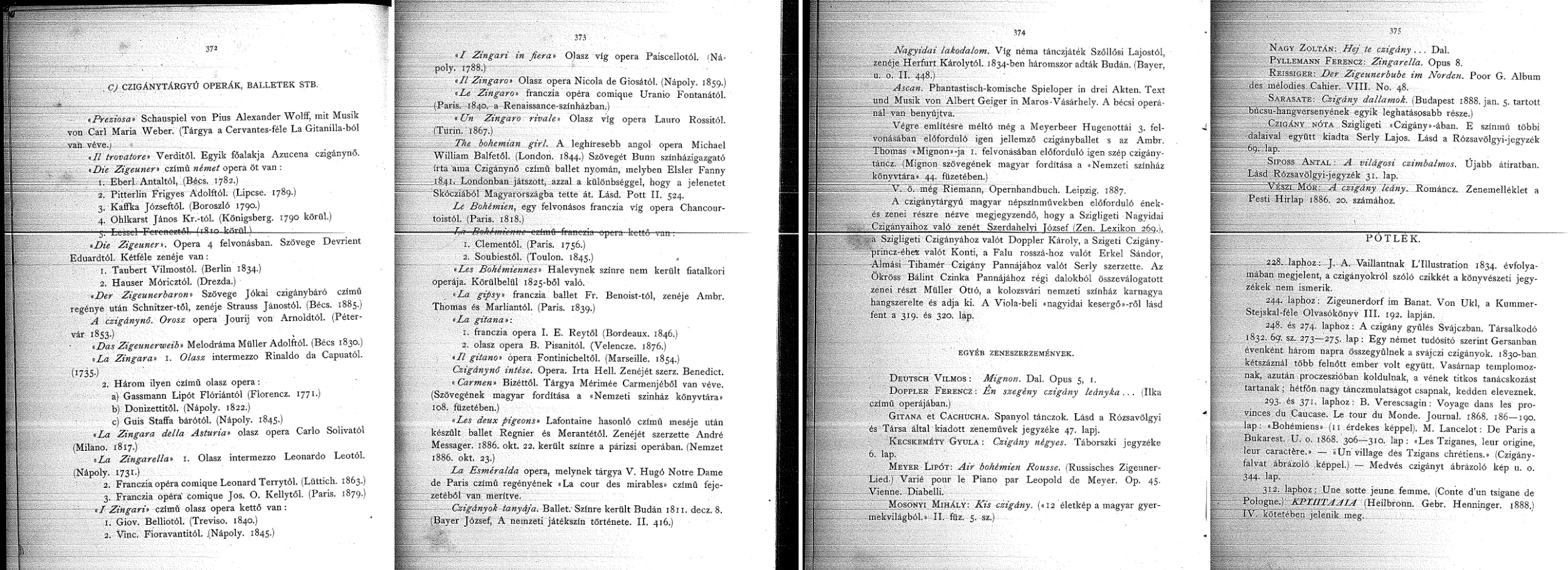

This was not the first time that Emil Ponori Thewrewk had sought the help of the Viennese music critic and aesthete Hanslick. The result of their correspondence is the list of Anacreon operas, which Ponori Thewrewk attached to his Hungarian translation of Anacreon (1885); volume published in the Academy’s series of Greek and Latin Masterpieces.

National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Levelestar 10743

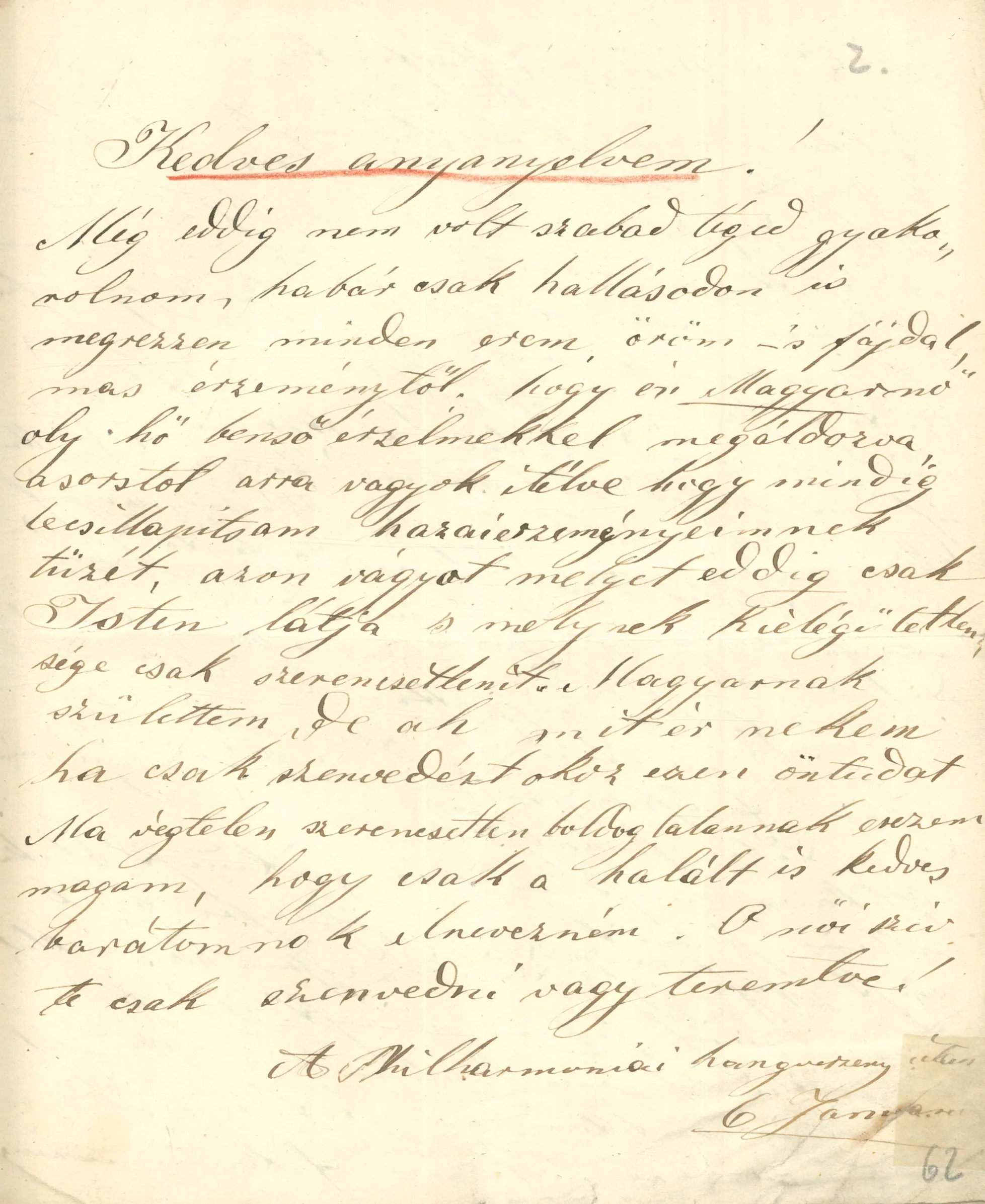

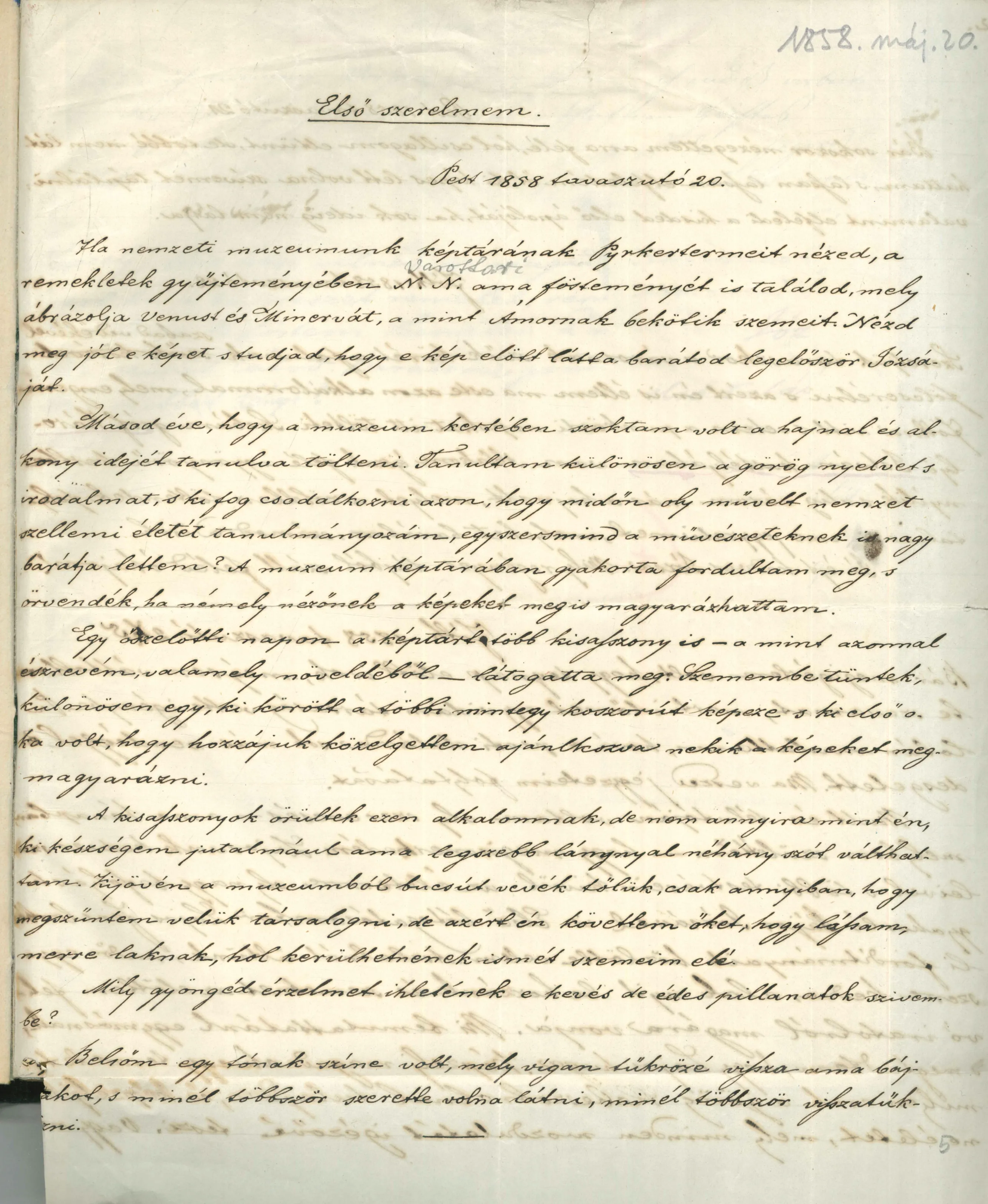

While Ponori Thewrewk primarily translated from Greek, his first wife, Josephine Matlekovits, nicknamed Miss Józsa (1841–1864), translated The Sorrows of Young Werther by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe into Hungarian.15 Inspired by this sentimentalist epistolary novel and on the advice of her suitor, Emil Ponori Thewrewk, Miss Józsa kept a diary. The language of the entries is German, up until the 2nd season ticket concert of the Philharmonic Society held at the National Museum on 6 January 1861, under the baton of Ferenc Erkel. The program featured:

1. Robert Schumann: Symphony no. 1 ‘Spring’ in B flat major, Op. 38

2. Ferenc Erkel: Bánk bán – Finale (collaborating opera singers: Kornélia Hollósy, Károly Kőszeghy)

3. Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61 – 1st movement (soloist: Ede Reményi)

4. Mihály Mosonyi: Festive Music (Ünnepi zene)16

After the evening and on the occasion of it, Miss Józsa noted her first Hungarian diary entry.

HAS LIC Department of Manuscripts & Rare Books, Történelem napló 4r 20

Another diary entry in Hungarian, presumably pasted in later, in Emil’s handwriting, records their first meeting in the gallery of the National Museum.

HAS LIC Department of Manuscripts & Rare Books, Történelem napló 4r 20

Emil Ponori Thewrewk immortalized her muse in his poems and married her in 1862. From their short marriage only one child was born, the journalist István Thewrewk (1863–1931).

My love

Life is beautiful if a strong heart

Blows its troubles far away;

Beautiful, if with firm commitment

We break down its numerous obstacles.

I embrace you tightly as a man,

I hold you, Józsa, as my holy property;

No curse separates me from you, dear

No blessing shall be my seducer.

While on this earth, I live for you –

Only death separates me from you;

Neither the grasp of death fears me:

I am immortal through my soul.

The mutual attraction of the bodies

What else is, if not love forever?

In our grave, my soul’s flames

Mixes me with your ashes.

Buda, 2 May 1862.17

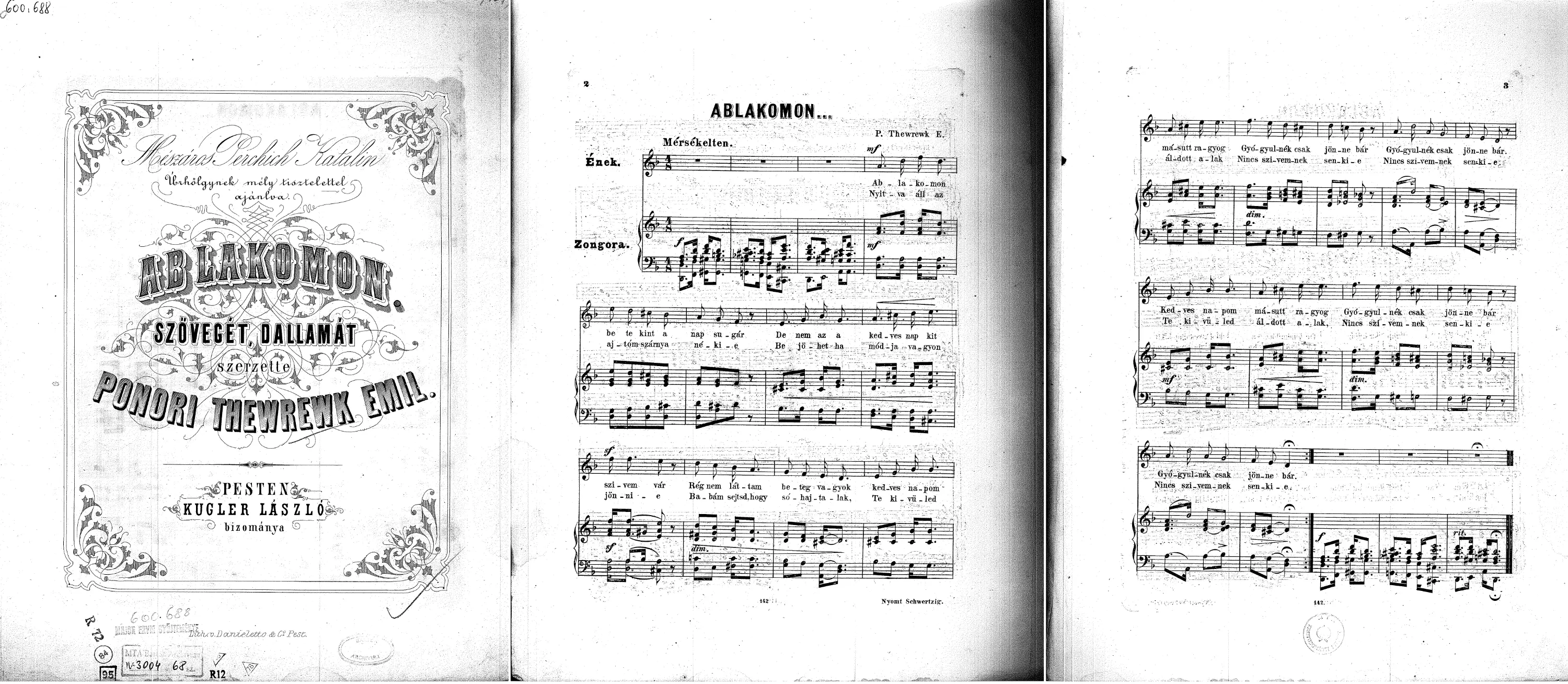

Several of Ponori Thewrewk’s poems were set to music, for instance the Az árva lány panasza (‘The Complaint of the Orphan Girl’), Eső csap a fák lombjára (‘Rain Falls on the Foliage’) and Esti sóhaj (‘Evening Sigh’) by Henrik Gobbi (1841–1920; he was acquainted with Liszt).18 Ponori Thewrewk himself also set his poems to music. He dedicated the Ablakomon (‘On My Window’) song to his former student and later second wife, Katalin Mészáros Perchich (1841–1905). About their wedding ceremony they contacted Mayor Kammermayer, Pastor Scholtz, and provost Mihály Bogisich. Finally, on the afternoon of 10 January 1885, they swore eternal fidelity to each other in the Lutheran Church of Buda Castle. Although Bogisich regretted that he could not marry them, he congratulated the young couple all the more cordially.19

Library of Musicology of the Institute for Musicology, RCH HUN-REN, 600.688

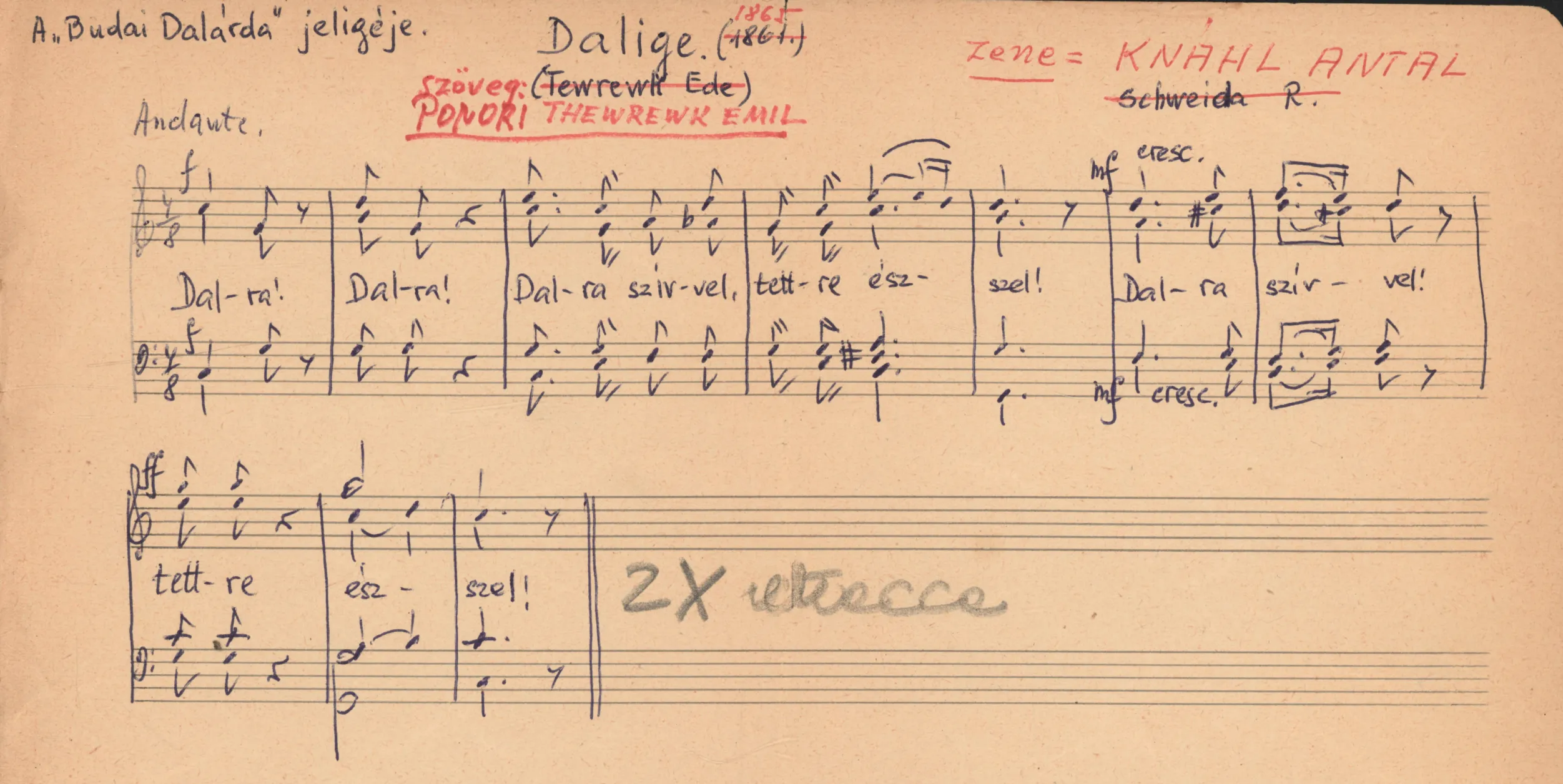

This popular art song was probably composed and published in the second half of the 1860s. A copy was sent in a letter of thanks to the Buda Men’s Choral Society, of which Emil Ponori Thewrewk was a member at the time. Ponori Thewrewk even wrote the verses of the Buda Men’s Choral Society’s official motto. The motto was set to music by Antal Knahl, the choirmaster of the Buda Men’s Choral Society and later director of the Buda Academy of Music (1868–1875).

Research Library of the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music, RK 4. 194

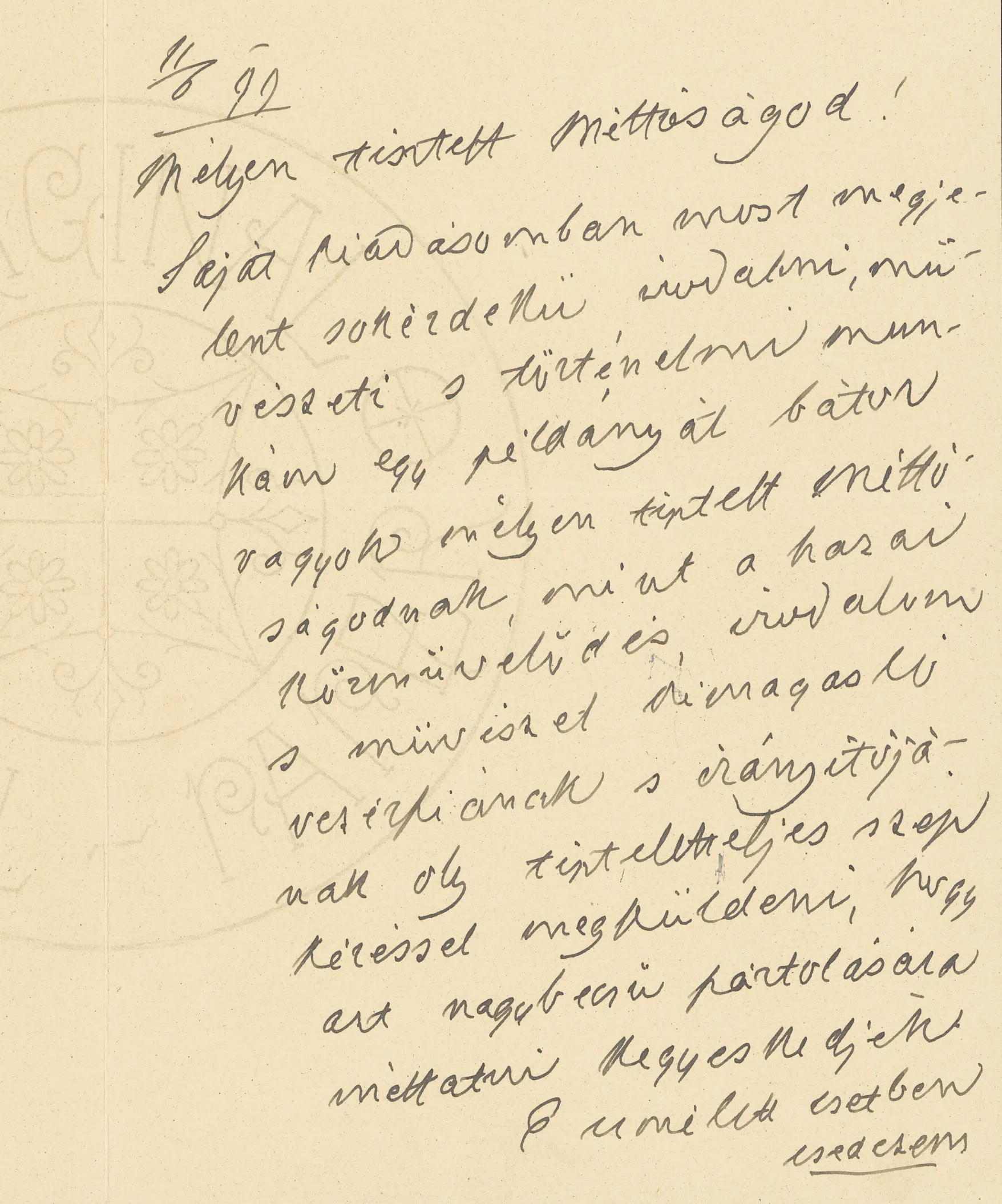

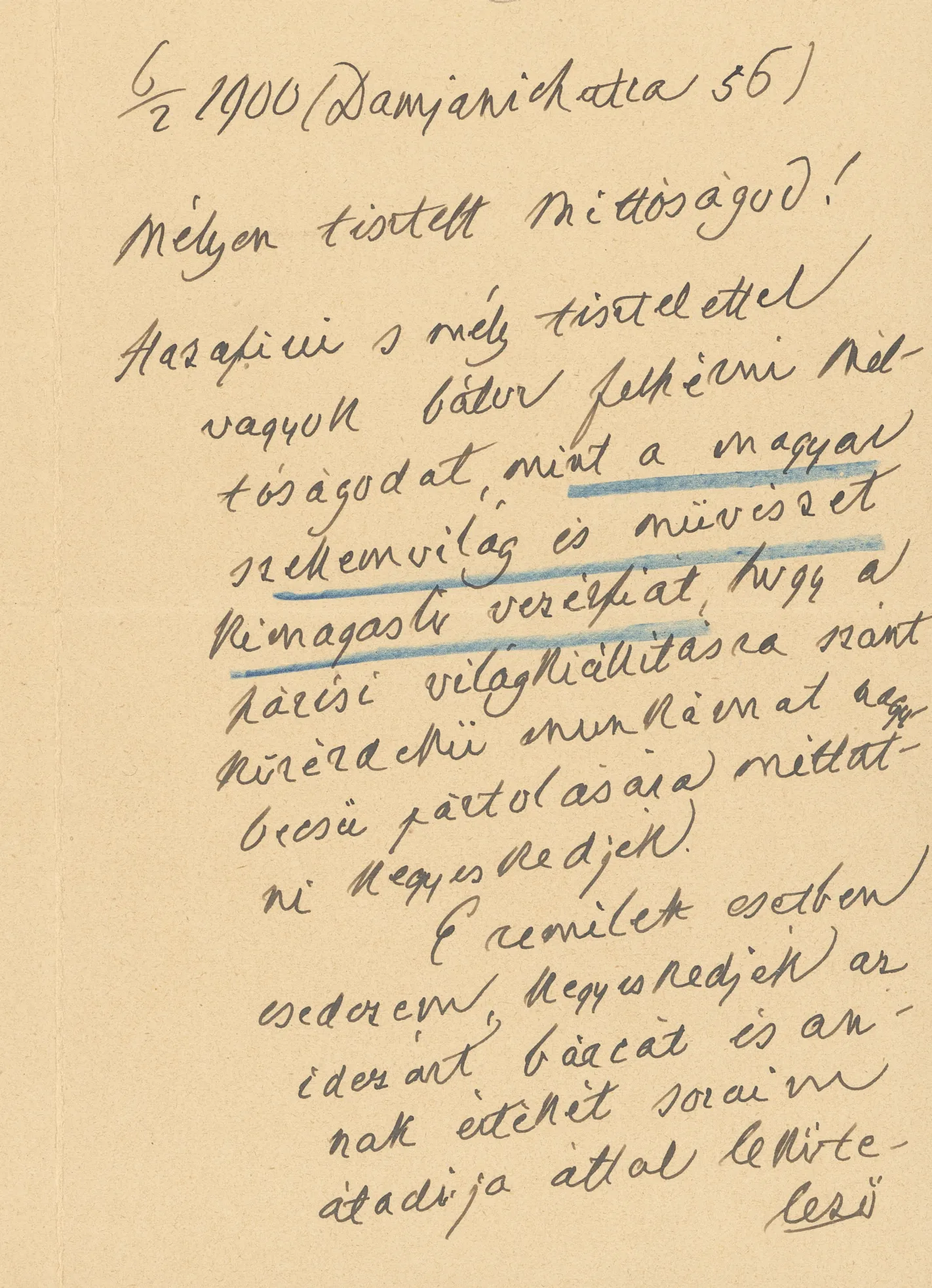

This, a few bars long motto was also published in the Zenészeti Lapok (on 12 October 1865, issue VI, number 2). This first Hungarian-language music journal (1860–1876) also functioned as the press organ of the choral movement, as its editor-in-chief was Kornél Ábrányi Sr., secretary and later president of the National Choral Society. As a composer, Ábrányi significantly enriched the choral repertoire, but composed numerous Hungarian fantasies, too. As a music historian, he wrote, among others, the history of choral societies.20 He even sent at least two of his volumes for patronage to the “outstanding leader of the Hungarian intellectual and artistic world”,21 i.e. Emil Ponori Thewrewk. One of the volumes, a “very interesting literary, artistic and historical work”, is presumably the 1899 memoir Képek a múlt és jelenből (‘Pictures from Past and Present’).

National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Levelestar 176

The other volume is Ábrányi’s A magyar zene a 19-ik században (‘Hungarian Music in the 19th Century’), the “work of public interest intended for the Paris World Exhibition” (in 1900).

National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Levelestar 176

Emil Ponori Thewrewk was considered an authority through his work. He was not only in contact with the renowned figures of the musical world of his time, but also enjoyed their respect. Like many of his contemporaries, music was not his vocation or source of livelihood. He explored any topic primarily as a scientist, a classical philologist, but only as a music lover and poet. Through his essays and a few folk songs, he successfully combined his “hobbies” – the rhythm of music and text, speech and melody, – not only in theory, but also in practice. The life and work of Emil Ponori Thewrewk exemplifies that in the second half of the 19th century, as always, music was a debate topic for both amateurs and professionals, from all fields of culture and science.

Translated & curated by Sára Aksza Grosz

1 About the editorial work of Emil Ponori Thewrewk see in detail Grosz Sára Aksza: Liszt-bibliográfia az Egyetemes Philologiai Közlöny hasábjain 1887-1918 [“Liszt bibliography on the columns of the Universal Philological Journal 1887–1918”] (Budapest, HUN-REN BTK Zenetudományi Intézet, Magyar Zenetörténeti Osztály, 2023).

2 Emil Ponori Thewrewk: „Budapest”, Magyar Nyelv 9 (1913), 192; same author: „Buda, Pest, Budapest”, Magyar Nyelv 12 (1916), 20-21; same author: „Széchenyi-Lánchíd”, Magyar Nyelv 12 (1916), 20.

3 Translated by Sára Aksza Grosz. Quote in original: „Semmiféle várost nem kedveltem még annyira mint Pestet; ámde ne hidd, hogy tájéka vagy épületei hanem egynémely lakói miatt. Miután prózai költeményeket már más helyt irtam, itt látom érzelmeimnek kikeltét, mely megmelegíté szívemet s megindítá dalainak folyamát. Ennek partján Józsa áll, s ezért ne csodálja senki, hogy minden alálejtő hab az ő képét tükrözi vissza.” See the letter of Emil Ponori Thewrewk to Lajos Matlekovits, Pest, 7 April 1858, Wednesday from the journal of Emil Ponori Thewrewk, National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Quart. Hung. 2526/6, 17.

4 Grosz Sára Aksza: „»Lisztnek egy barátja« – Ponori Thewrewk Emil” [“‘A friend of Liszt’ – Emil Ponori Thewrewk”] , in Kim Katalin – Horváth Pál (eds.): Budapesti mindennapok Erkel és Liszt korában: Ünnepi konferencia Eckhardt Mária tiszteletére [Everday Life in Budapest in the Age of Erkel and Liszt: Gala Conference in Honor of Mária Eckhardt] (Budapest, HUN-REN Bölcsészettudományi Kutatóközpont, Zenetudományi Intézet, 2023), 279–313.

5 For example: A Hon 11/29 (11 November 1873), Fővárosi Lapok 13/260 (12 November 1873), Ponori Thewrewk Emil: „Liszt Ferenc”, Budapesti Hírlap 30/246 (6 October 1910.), same author: „Liszt Ferenc”, Budapesti Hírlap 31/90 (16 April 1911).

6 See Legánÿ Dezső: Liszt Ferenc Magyarországon 1869–1873 [“Ferenc Liszt in Hungary 1869–1873”] (Budapest, Zeneműkiadó Vállalat, 1976), 182. See also the list of dates written by Ponori Thewrewk concerning his acquaintances with Ferenc Liszt, National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Fond XII/1331/3rd envelope. For the playbill see National Széchényi Library, Theatre Department, playbill of the Pest National Theater, 10 November 1873.

7 Ponori Thewrewk Emil: „A magyar zene rhythmusa” [“The Rhythm of Hungarian Music”], in Kovács Béla Lóránt (ed.): Ponori Thewrewk Emil: A hang mint műanyag. Válogatott zenészeti, költészeti és nyelvészeti tanulmányok [Emil Ponori Thewrewk: The Sound as Source of Composition. Selected Essays on Music, Poetry and Linguistics] (Budapest, Szépirodalmi Figyelő, 2008), 51.

8 Ferenc Liszt: Des Bohémiens et de leur musique en Hongrie (Paris, Librairie Nouvelle – A. Bourdilliat, 1859). For Hungarian translation see Liszt Ferenc: A czigányokról és a czigány zenéről Magyarországon (Pest, Heckenast Gusztáv, 1861).

9 Vizinger Zsolt: „Harmónia & Hungária: Az első magyar zeneszerző-társaságok története” [“Harmónia & Hungária – The History of the First Hungarian Composers’ Societies”], in Kim – Horváth (eds.): Budapesti mindennapok Erkel és Liszt korában [Everyday Life in Budapest in the Age of Erkel and Liszt], 202–206.

10 The journal of Emil Ponori Thewrewk, National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Quart. Hung. 2526/15, unnumbered pages at the end of the volume.

11 Ritoók Zsigmond: Ponori Thewrewk Emil (Budapest, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1993) (= A Múlt Magyar Tudósai) [= “The Hungarian Scholars of the Past”], 108.

12 The letter of Emil [Ponori] Thewrewk to Kornél Ábrányi Sr., 29 January 1887., National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Fond XII/1119.

13 The journal of Emil Ponori Thewrewk, National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Quart. Hung. 2526/10, 99v, Friday, 4 February 1887.

14 This work is until now one of the basic books on the topic of Hungarian Gypsy culture. Short after the Hungarian edition, a German translation was published, however, without the literary guide of Emil Ponori Thewrewk. See Ritoók: Ponori Thewrewk Emil, 110–111.

15 The translation of Miss Józsa is found in the Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Department of Manuscripts & Rare Books as Nyelvtudomány 4r 112. The manuscript has no year indication, it consists of 14 ff, and features the red ink corrections of Emil Ponori Thewrewk. The translation is also included in M. Nyelvtudomány 4r 112/7 manuscript kept in the same department. In it the translation is dated from year 1857.

16 For the program and performers of the concert see Bónis Ferenc: A Budapesti Filharmóniai Társaság százötven esztendeje 1853–2003 [“One Hundred and 50 Years of the Budapest Philharmonic Society 1853–2003”] (Budapest, Budapesti Filharmóniai Társaság–Balassi Kiadó, 2005), the attached CD was compiled by Nóra Wellmann.

17

Translated by Sára Aksza Grosz from Emil Ponori Thewrewk:

Józsa. Költemények [“Józsa. Poems”] (Pest, Kilián György, 1862), 7–8. The poem in original:

Szerelmem

Szép az élet hogyha erős kebel

Széjjel küldi annak bajait;

Szép ha szilárd előtörekvéssel

Döntve döntjük számos gátjait.

Férfiasan átkarolva téged

Tartlak, Józsa, mint szent birtokom;

Semmi átok nem szakít el tőled,

Semmi áldás nem lesz csábítóm.

Érted élek, míg e földön élek –

Tőled csak a halál választ el;

Sőt a halál karjától sem félek:

Halhatatlan vagyok lelkemmel.

És a testek közös vonzódása

Mi más mint egy örök szeretet?

Sírunkban is lelkem lángolása

Hamvaidhoz vegyít engemet.

Buda 1862. tavaszutó 2.

18 Dalok zongorakísérettel: Az árva lány panasza [“Songs with Piano Accompaniment: The Complaint of the Orphan Gir”], National Széchényi Library Theatre and Music Department, Ms. Mus. 1173; Eső csap a fák lombjára [“Rain Falls on the Foliage”] same library and department, Ms. Mus. 1306; Esti sóhaj [“Evening Sigh”], same library and department, Ms. Mus. 1301 [Dalok címlap nélkül] [“Songs without Title Pages”]. The latter is a printed edition and includes also the song entitled Eső csap a fák lombjára [“Rain Falls on the Foliage”].

19 The journal of Emil Ponori Thewrewk, National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Quart. Hung. 2526/10, 1 and 3v, 28 January [1886].

20 Id. Ábrányi Kornél: Az Orsz. M. Daláregyesület negyedszázados története 1867-től 1892-ig [The Quarter-Century History of the National Hungarian Choral Association from 1867 to 1892], I-II (Budapest: Orsz. Magy. Daláregyesület, 1892, 1898). About the role of Ábrányi within the choral movement see in detail Gusztin Rudolf: „Életem s csekély munkaerőm javát vette igénybe.“ id. Ábrányi Kornél és a magyarországi dalármozgalom kapcsolata [“It Demanded on the Best of My Life and Petty Work Capacities” – The Relationship Between Kornél Ábrányi Sr. and the Choral Movement in Hungary] (Budapest, Zenetudományi Intézet, Magyar Zenetörténeti Osztály, 2022). For the list of the articles concerning the choral movement and published in the Zenészeti Lapok [Musical Papers] see in detail Gusztin Rudolf: Dalármozgalom a Zenészeti Lapokban 1860–1867 között. Sajtóadatbázis [Choral Movement on the Columns of the Zenészeti Lapok (Musical Papers) Between 1860 and 1867. Press Database (Budapest, BTK Zenetudományi Intézet, Magyar Zenetörténeti Osztály, 2020). About the choral movement in 19th century Hungary in general see Rudolf Gusztin: “Choral Movement and Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Hungary”, in Stanislav Tuksar – Vjera Katalinić – Petra Babić – Sara Ries (eds.): Glazba, umjetnosti i politika: revolucije i restauracije u Europi i Hrvatskoj, 1815-1860: uz 200. obljetnicu rođenja Vatroslava Lisinskog i 160. obljetnicu smrti bana Josipa Jelačića (Zagreb, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Croatian Musicological Society, 2021), 695 – 712. DOI: 10.21857/y6zolbr8nm (last accessed on 19 November 2024.) About the activity of Ábrányi as music historian see in detail Kim Katalin: „A döntő szó úgy is mindig és mindenben az idő jogához tartozik.” id. Ábrányi Kornél és a magyar zenetörténetírás [“The Decisive Word Always and in Everything Belongs to the Right of Time.” – Kornél Ábrányi Sr. and Hungarian Music Historiography] (Budapest, Zenetudományi Intézet, Magyar Zenetörténeti Osztály, 2022). About the compositions of Ábrányi see in detail this website and this article Vizinger Zsolt: „Komponálás tetszetős modorban.” Id. Ábrányi Kornél zeneművei [“Composing in a Pleasing manner.” The Musical Output of Kornél Ábrányi Sr.] (Budapest, Zenetudományi Intézet, Magyar Zenetörténeti Osztály, 2022).

21 The letter of Kornél Ábrányi Sr. to Emil Ponori Thewrewk, 6 February 1900, National Széchényi Library Manuscript Collection, Levelestar 176, 3rd letter.