Church Music Episodes from the Everyday Life of Pest Buda (1882–1898)

The 19th-century actors of the effervescent cultural life in the Castle District, including Ferenc Erkel and his father-in-law, the former choirmaster of the Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary (also known as the Matthias Church) in Buda, György Adler, Mihály Bogisich, Zsigmond Szautner and Mór Vavrinecz, were at the same time the most important representatives of Hungarian music life. If we follow the traces of their intellectual legacy, snapshots of one Budapest’s most important institutions in Hungarian church music life will unfold before our eyes. The musical episodes of the Mátyás Church’s history between 1882 and 1893 show us, among other things, how preservation and innovation can be reconciled.

Matthias Church Parish Archives

Mihály Bogisich (1839–1919), the Herald of the Church Music Revival

Born in Pest, Mihály Bogisich was a chaplain in the Inner City, and, in 1896, he became the titular bishop of Pristina; the reform efforts in Budapest aimed at the renewal of the Latin rite Catholic church music were concentrated in his hands. Mihály Bogisich’ musical and theological studies, his professional training and his contacts abroad provided him with the necessary basis to grow into the leading figure not only in the liturgical musical practice of the Hungarian capital but also in the renewal of Hungarian church music.

Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences D 12166

Bogisch’ vision of an ideal church music practice, including the vocal repertoire, was in line with the convictions of Zsigmond Szautner (1844–1910), another outstanding personality of Budapest’s musical life. The latter was the holder of several leading positions: he was the director, conductor, and teacher of the Buda Academy of Singing and Music from 1878; then, until 1885–1886, he directed the Buda Church Music Society and served as temporary conductor of the Castle Parish Church. Szautner prepared with a strong vision the introduction of church music reforms in Hungary. Both Bogisich and Szautner regarded the initiatives of the Caecilian movement from Bavaria as a model. In 1880, Bogisich believed that, following his plans, it would have been possible to introduce and consolidate reforms in Hungarian church music within a decade. Our data on the history of the Caecilian movement in Hungary show the unrealistic nature of this conception, e.g. it took seventeen years after the formulation of the plans to get to establishment of the National Hungarian Caecilian Association (hereafter: NHCA). We might rightly pose these question: What factors could have delayed the institutionalisation of the reform in Hungary to such a significant extent? Moreover, from the perspective of the history of the Caecilian movement in Hungary as a whole, should we really regard this decade and a half as a period of temporary stagnation?

The Attempted Reform: Snapshots from the Everyday Life of the Religious Music Practice at the Matthias Church (1882–1898)

The period between 1882 and 1898, i.e. the period of Mihály Bogisich’ service at the Matthias Church, provides useful answers for the questions raised above. From the perspective of the history of Hungarian church music, we find the immediate antecedents of the NHCA’s establishment. On the other hand, this was a significant period of Bogisich’ church music career, providing us with a wealth of data. His appointment by election at the Matthias Church on 28 June 1882 created new opportunities for him as a priest and composer, committed to church music reform. As parish priest of the capital’s most important church, he could finally put into practice the reform ideas he had developed earlier.

Three groups of sources provided the starting point for reconstructing the musical life of the Matthias Church of the time. Breaking with the practice observed before the 1880s, the historia domus of the parish church began to document the musical events in Bogisich’ time in remarkable detail. In addition, the Parish Office Archives also preserved valuable music-related documents, which support and occasionally supplement Bogisich’ records in the historia domus. The music collection of the Parish Archives is our third set of sources, containing Bogisich’ choral works and transcriptions for mixed and male choir.

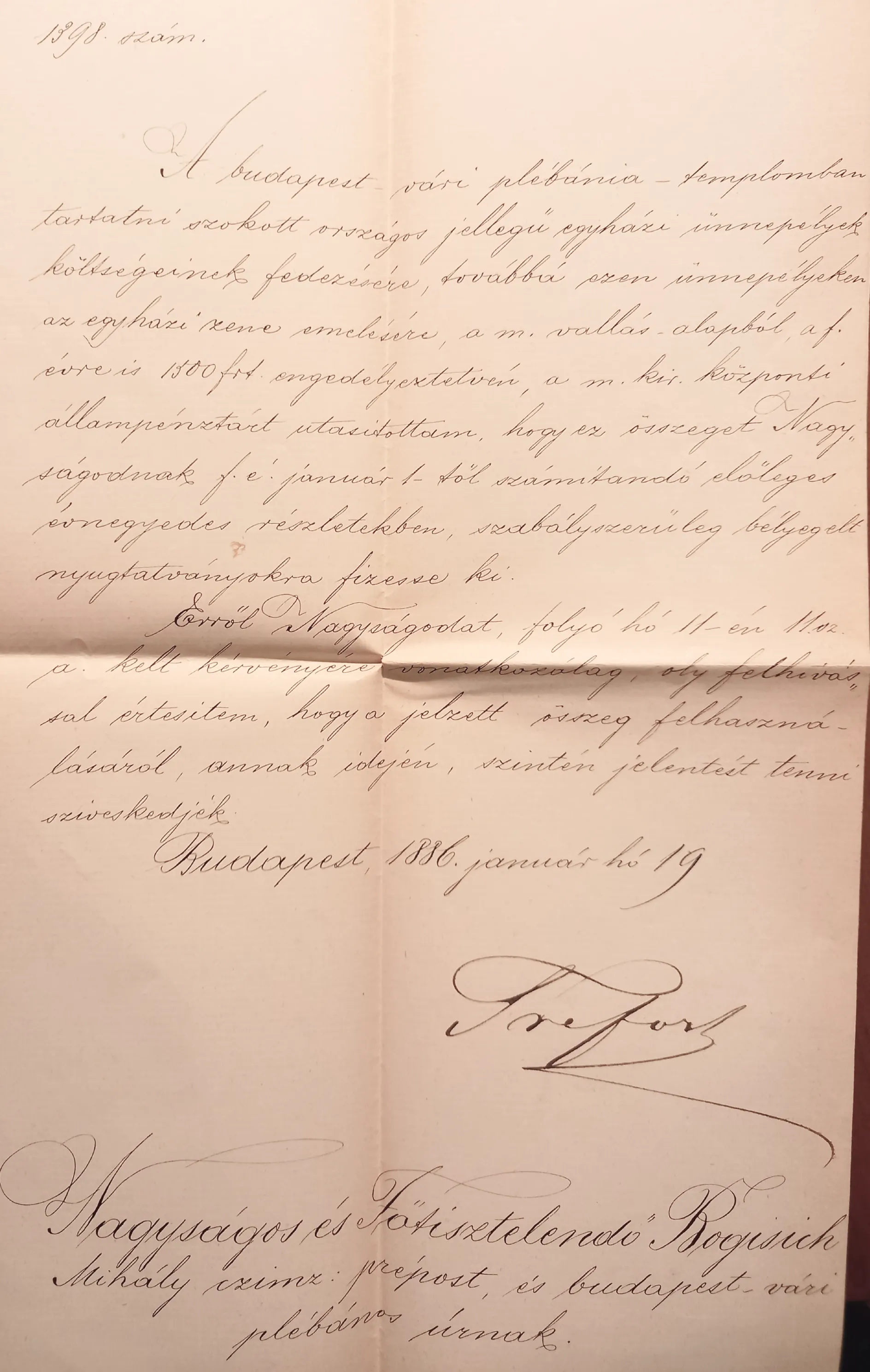

The above groups of sources suggest that Bogisich made a complex attempt aimed at the renewal of the musical life at the Matthias Church. The Hungarian language as such played a central role in the resolute measures he took. The parish priest of the Buda Castle paid special attention to the use of the Hungarian in both the sermons and the church hymns. He also changes concerning the musical ensembles, including the number of their members, and diversified the repertoire with new a cappella compositions and folk-hymn arrangements. It became apparent that the renewal of the church’s musical profile would only be possible with new financial resources. To do make that happen, Bogisich drew on his previous contacts. As a result, Ágoston Trefort, the Minister of Religion and Public Education, donated 500 forints (decree of 20 August 1883), and he contributed 1,500 forints a year, from 1 January 1884 until his death in August 1888, for the transformation of the church ensembles and the organisation of national festivities.

Matthias Church Parish Archives 1886/12

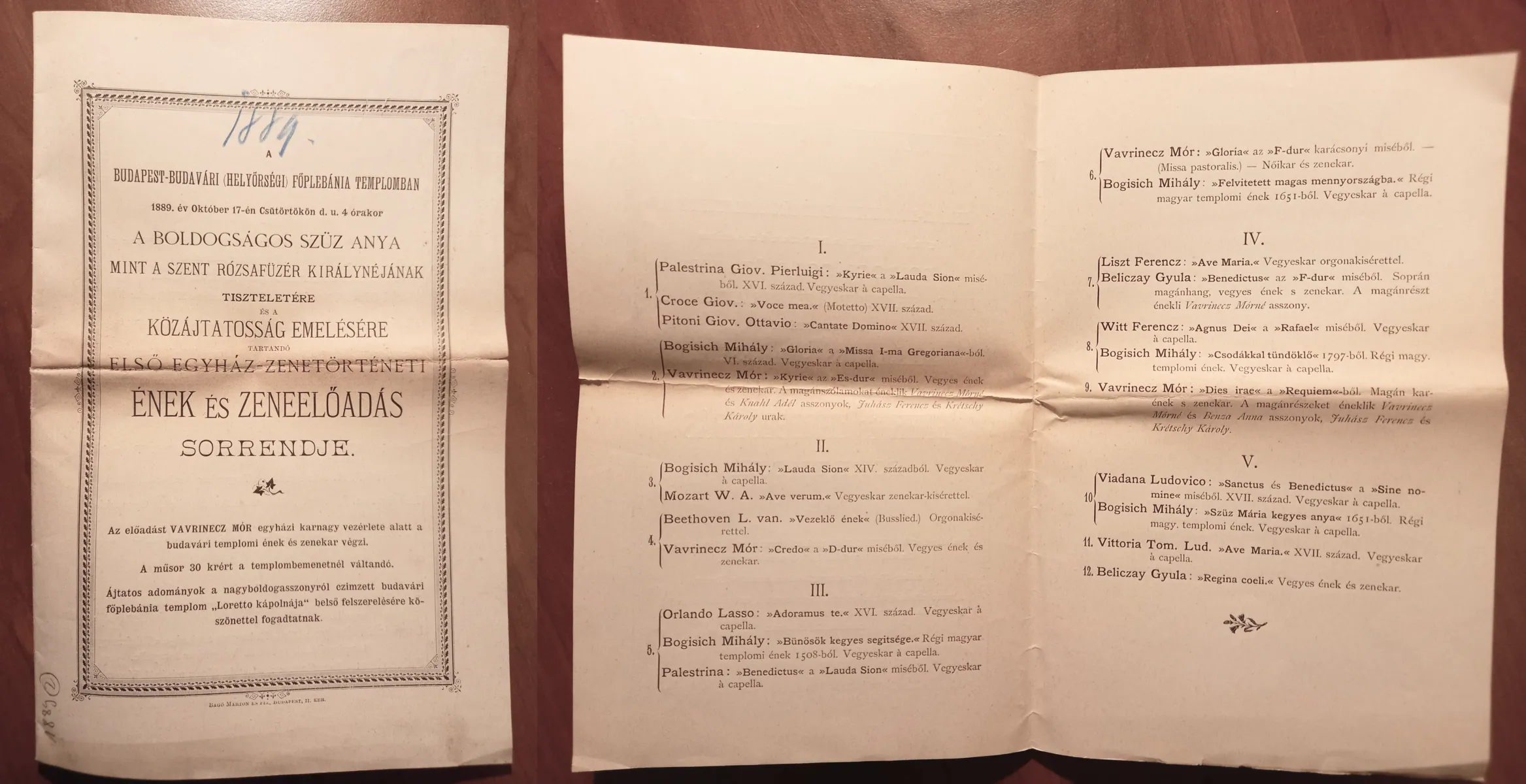

Following Trefort’s death, his successor, Albin Csáky, also gave permission to transfer the previous amount from the religious fund. Thanks to this support, Bogisich was able to present his ideal of church music to the public in a more representative setting, in the form of so-called ‘music performances on the history of church music.’ A total of twelve programs of Bogisich’ performances, from the period between 1882 and 1898, have been preserved at the Parish Archives.

Matthias Church Parish Archives 1889/2

According to our current knowledge, at the time of Bogisich’ inauguration, the musical life of the Matthias Church was of low professional standards. György Adler, the then regens chori, was appointed organist, cantor and music director after the death of his predecessor, Ferenc Váray, of the on 29 March 1862. However, the level of musical excellence achieved under Adler certainly underwent a gradual decline, with Váray’s prolonged and lung disease. The decrease in the data concerning the musical life, recorded by József Ráth, the parish priest who took office in 1867, suggests that quality church music cased to be as important in the daily life of the church as it had been under Adler or, later, under Zsigmond Szautner and Mór Vavrinecz (1858–1913), both appointed by Bogisich

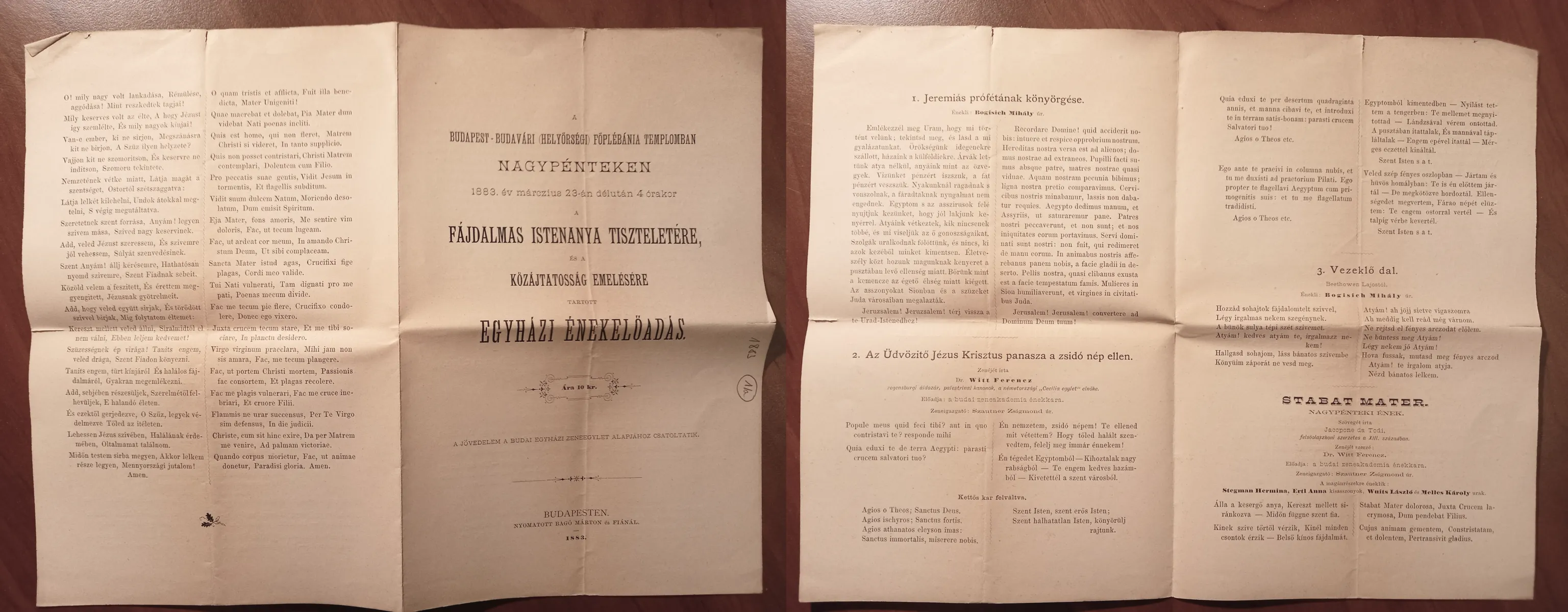

The change that occurred in the period between 1882 and 1898 is also mirrored in the changes in personnel. According to the chronicle of the historia domus, Váray who was in poor health at the time of Bogisich’ appointment was only able to perform his duties on several occasions through deputies. E.g. during Holy Week of 1883, at Váray’s express request, it was Bogisich who conducted the musical ensemble during the services, while Baron Károly Hornig (1840–1917), the elected bishop of Skardona and ministerial councillor, served at the altar. Bogisich, however, turned this situation of necessity into an opportunity: he personally put together the program for the Good Friday Religious Singing Performance (23 March 1883) in the spirit of the Caecilian Revival. Bogisich’ reformist intentions are also reflected by the fact that Szautner’s ensemble, the Choir of the Buda Academy of Singing and Music, included into the Good Friday program choral works by Franz Xaver Witt (1834–1888), the leading figure of Bavarian Caecilian movement.

Matthias Church Parish Archives 1883/1/a

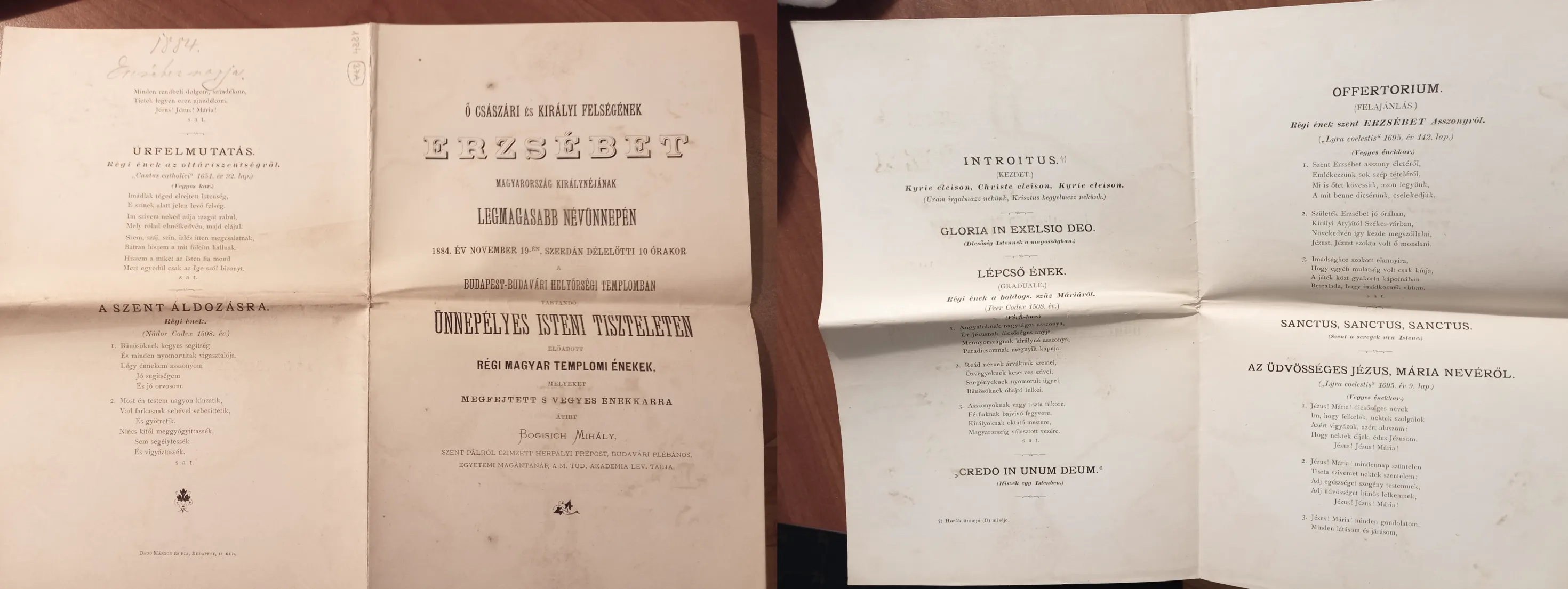

Although Bogisich was remarkably careful in documenting the musical life of the church, the historia domus contains only one quantified record of the performing apparatus involved. The entry dated 31 December 1883 records that a mixed choir of 20 people performed Bogisich’ arrangements of 17th-century folk hymns at the liturgy for Queen Elisabeth’s birthday. However, this information is somewhat at odds with the description Dezső Legánÿ gave in his 1986 volume Liszt and His Country. Referring to a draft submitted by Bogisich in the autumn of 1883, Legánÿ reported that the Buda Castle parish priest had envisaged the creation of a choir of twenty boys at the express request of Trefort, and following the example of Regensburg. Several entries in the music collection attest to the participation of a much larger vocal ensemble, but even so, attaining the Regensburg ideal remained a dream. What we know for sure, is the only in November 1883, at the Mass held on Queen Elisabeth’s name day, did a choir of boys and adult men perform. The ensemble consisted of students from the Buda State Male Teachers’ Training School. Apart from this exception, the surviving documentation suggests that female choir members probably sang the treble parts, and vocal performances were often accompanied by the orchestra.

Matthias Church Parish Archives 1884/37a

New Choirmaster Wanted

Reorganizing the ensemble proved as difficult as finding the ideal choirmaster. Following the tragic death on 24 February 1885 of Antal Kneifel, the regens chori appointed the previous year, the posts of the cantor and music director remained vacant for quite some time. This lack of interest in the position of choirmaster is explained by were several reasons. László Tardy, the recently retired choirmaster of the Matthias Church, pointed out in his 1984 case study that reasons included the church’s exile situation due to the restoration begun in October 1875 (until 1893, services were held in the Garrison Church), and the low remuneration for the post of music director, which was not attractive to applicants. Bogisich temporarily appointed Zsigmondy Szautner, director of both the Buda Academy of Singing and Music and the Buda Church Music Society (BCMS). The two men were connected through the BCMS, where Bogisich served as secretary and private singer for almost a decade and a half. Bogisich built up a fairly close relationship between the Matthias Church, the BCMS, and the Buda Academy of Singing and Music, also under Szautner’s leadership. The cooperation resulted in the regular participation of the Choir of the Buda Music Academy in the religious music performances and Trefort’s declaration of approval of 20 August 1883, according to which the music performances were placed under the leadership of the Buda Church Music Society. Moreover, in his submission to the Ministry of autumn 1883 mentioned above, Bogisich thought of the advantages and even considered the possibility of merging the church choir and the Buda Church Music Society. Eventually, Bogisich was able to find the ideal candidate for choirmaster position: according to Bogisich’ preliminary application (1886/93), on 7 October 1886 the Metropolitan Council of Budapest appointed a young, agile and passionate choirmaster to the post of regens chori of the Matthias Church in the person of Mór Vavrinecz.

The Renewed Church Music Repertoire

The collaboration between Vavrinecz, who was equally talented as a composer and a choral conductor, and Bogisich, who was obviously committed to the Reform of church music, opened a new era in the history of the Matthias Church. The most remarkable result of their joint work was the assembling of a new repertoire, which was to affect the perception of Hungarian church music on the long run. Within the Hungarian Catholic church music of the second half of the 19th century, we can distinguish four main trends of stylistic and aesthetic nature. The first of these was the Viennese Classicism, manifesting through the predilection for the religious works by Joseph Haydn (1732–1809), Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791), and Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827). The second category was made up of Caecilian composers from Bavaria as well as the new works composed by Hungarian church musicians who imitated them. The third type was reserved for 16th-century vocal polyphony. The fourth layer, however, was characterised by a completely new approach from the perspective of the history of the Caecilian movement in Hungary as a whole. The work of Mihály Bogisich brought namely the ancient Hungarian folk hymn repertoire to the fore.

The above layering can be detected in both the style and apparatus of the repertoire reconstructed from the church’s surviving 19th-century music collection and historia domus. The significant presence of works employing orchestra and vocal soloists demonstrates that – in addition to the inclusion of a cappella compositions in line with the Caecilian canon – the continuation of tradition was a crucial part of reform concept as cultivated by Bogisich and Vavrinecz. As a result, even during Mihály Bogisich’ time, in addition to the choral works proposed by the Caecilians, the Requiem of Georg Lickl (1769–1843), the regens chori of Pécs, or the Ave Maria by Luigi Cherubini (1760–1842) for solo voice and orchestra were performed as well.

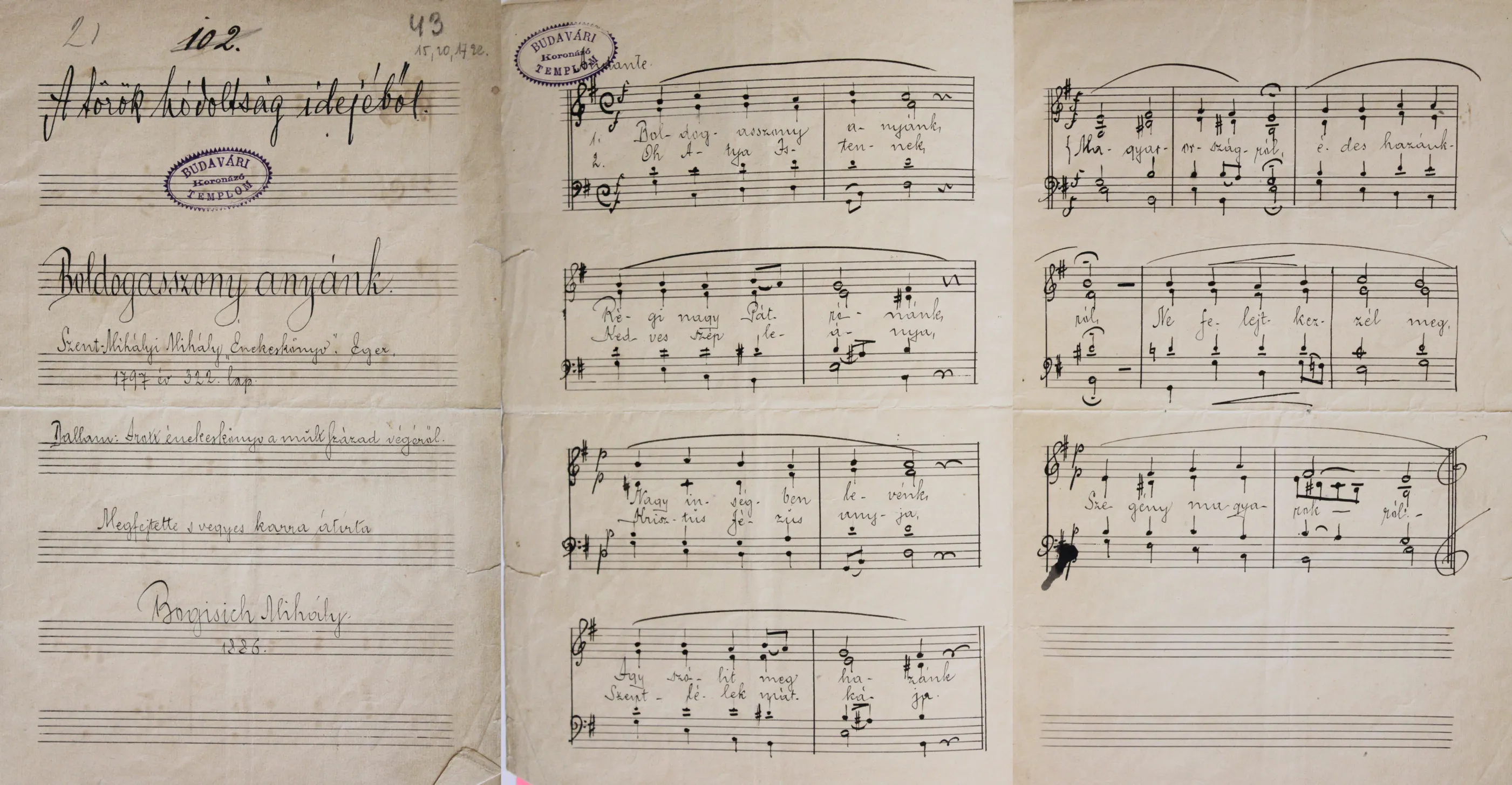

It is striking that from the very beginning, Bogisich was careful to balance the Classical part of the musical repertoire he assembled with typically Caecilian compositions from Bavaria and with his own arrangements of folk hymns, in keeping with the reformist spirit he had envisaged. In 1888, he published a book of prayers and folk hymns, titled Őseink buzgósága [The Fervour of our Ancestors], which can be viewed as the summary of his efforts to promote folk hymns. The collection contains 135 hymns and their variants – i.e. a total of 160 melodies, originating from nine musically notated sources resulting from Bogisich’ research into folk hymns. For the first time in Hungarian music history, Bogisich approached these sources in a complex way, combining the skills of the music historian familiar with palaeography with those of the composer who saw new possibilities in the selected items. The preparatory work for The Fervour of Our Ancestors was in all likelihood intertwined with Bogisich’ work at the Matthias Church, as evidenced by the church’s archival music collection as well as by the archival documentation of the musical events that took place there. Out of the forty-one folk-hymn arrangements preserved in the music collection, which presumably were all performed by the church ensembles, only thirteen were omitted from the volume.

Matthias Church Archival Sheet Music Collection B 43

Over time, the professionalism of the reorganized church choir made it possible to perform larger works of 16th-century vocal polyphony. Bogisich’ efforts in this direction were of outstanding importance also for the history of Palestrina reception in Hungary. On 25 March 1890, Palestrina’s Missa papae Marcelli was performed for the first time in Hungary in the Garrison Church, which served as the temporary seat of the Buda Castle congregation.

In the Service of the Imperial Family

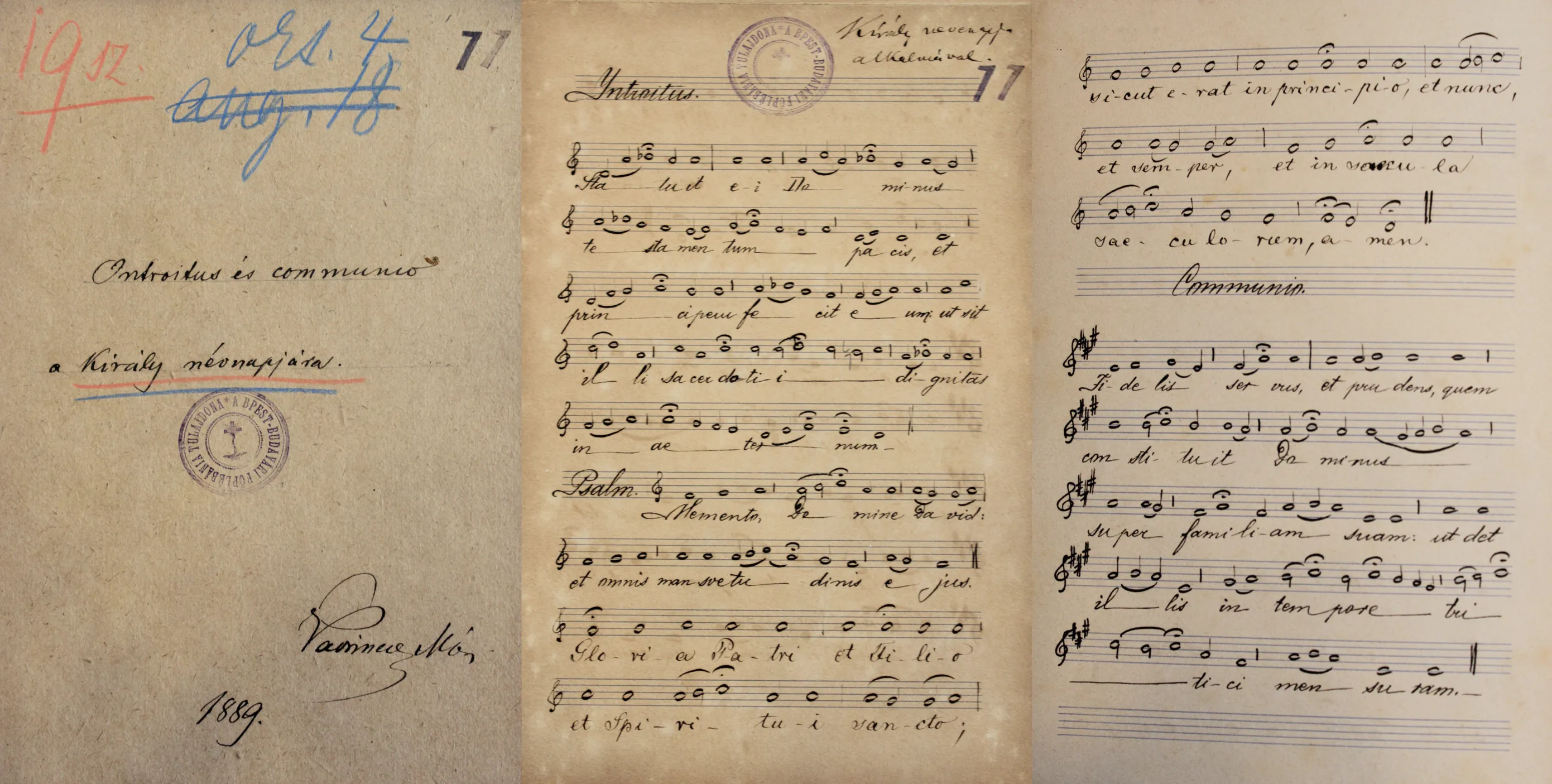

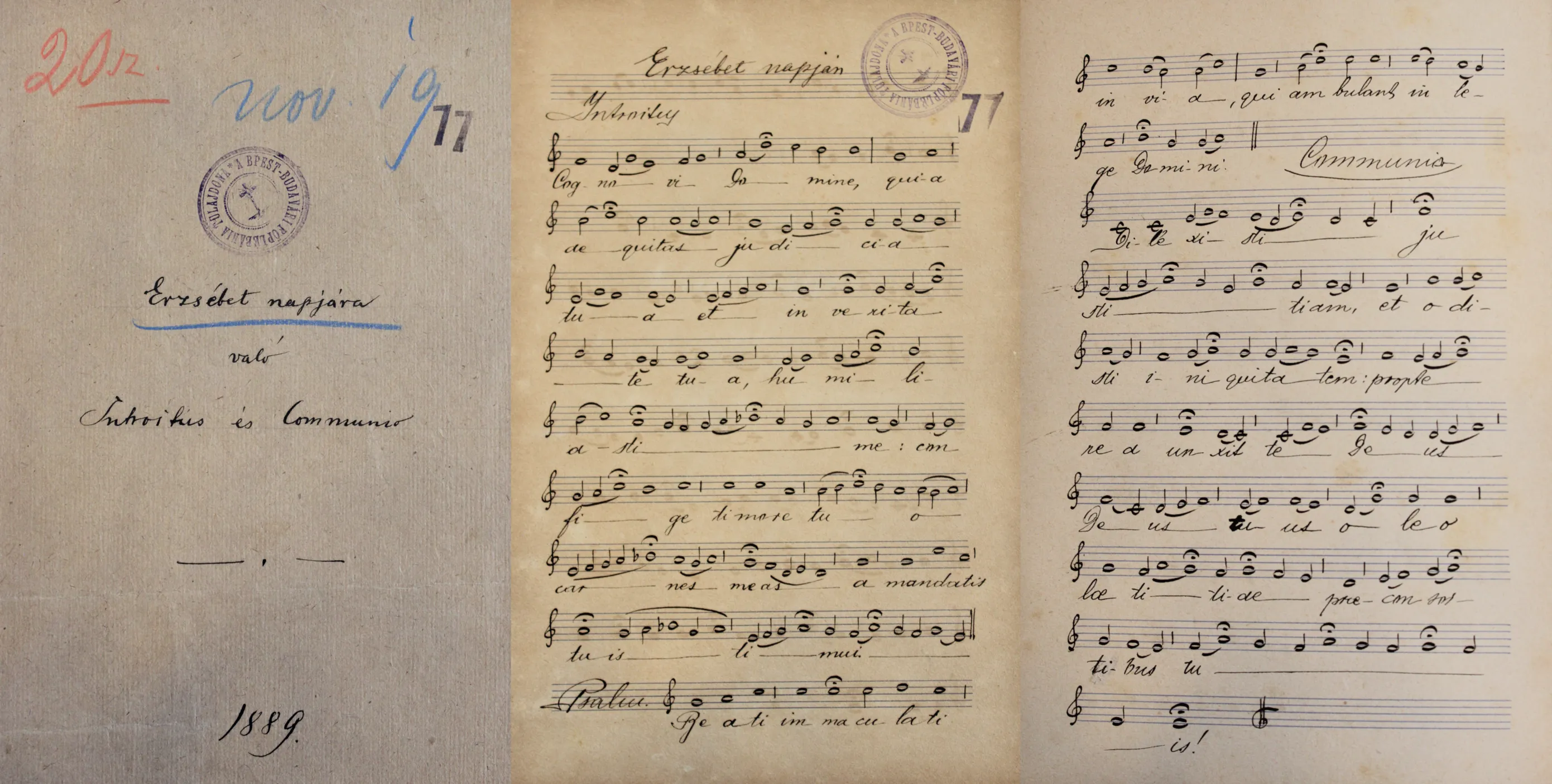

Even the first representative events occurring during Bogisich’ service reflect his Reform concept. He had special offprint editions produced for the festive ceremonies to mark the name days of Franz Joseph and Queen Elisabeth (4 October and 19 November 1882, respectively). The title page of the small booklets, containing the texts of the Mass hymns, made aware of the “ancient Hungarian church songs” to be performed, i.e. Bogisich openly declared the reduction of the repertoire inherited from the 1850s, which typically featured soloists and an orchestral apparatus. In addition to the released texts of the folk songs, readers were also informed about the works and the performers contributing to the church service, as well as the sources of the folk hymns. Bogisich’ precise and historically accurate work is demonstrated by the fact that the published texts are provided with exact source references. Thus, we know that he took the melodies from two 17th-century sources: the Cantus Catholici by János Kájoni (1651) and the Lyra coelestis by György Náray (1695). At the festive ceremony in October, the program consisted almost entirely of Bogisich’ arrangements, sung alternately by mixed and male choirs. From 1882, Bogisich published the male choir version of his arrangements, thus following the Caecilian choral ideal, in the supplements of the journal Religio (presumably modelled on the Bavarian Musica Sacra), as Hungarian church music did not have a dedicated press organ at the time. Katholikus Egyházi Zeneközlöny (Catholic Church Music Journal), the first church music journal published over a longer period, was only launched in December 1893. Among the works performed on the occasion of the imperial name day, only the Credo movement from Endre Zsasskovszky’s Mass in B flat major represented the classical style of the previous decades.

Matthias Church Archival Sheet Music Collection 77/19

Matthias Church Archival Sheet Music Collection 77/20

The festive ceremony in November featured movements performed by solo singers related to the Viennese Classicism and Romanticism, with Bogisich among the performers. Including Beethoven’s Busslied op. 48/6 (from Sechs Lieder von Gellert), a popular and frequently performed piece of the church repertoire.

Bogisich appeared several times as a solo singer, typically at the Good Friday Church Music Performances and at the services held for the Imperial family. On this occasion, too, Bogisich’ arrangements of folk hymns gave the stylistic counterpoint of the program. The ensemble was made up of boys and men from the Buda State Male Teachers’ Training School, taught by the school’s singing teacher, János Izák (1859–?).

In developing his reform plans, Bogisich gave equal weight to theoretical and practical considerations. His vision for the renewal of Catholic religious music in Hungary was undoubtedly influenced to a considerable extent by his own experience in shaping the music life of the Matthias Church. Although no clear statement to this effect has survived, it is possible that Bogisich saw in the process of renewing the church’s music life the prototype for the successful introduction of reform. However, his utopian vision formulated in 1880, namely that the reform measures were to be consolidated during a short decade in the music practice of the entire Hungarian Catholic church, was not proven, not even in the case of the Matthias Church. The balance of the church’s musical repertoire established by Bogisich gradually shifted to large-scale orchestral performances after his transfer to Esztergom in 1898. The roots of 19th-century church music practice were so strong that the reform measures introduced at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries could not be expected to produce long-term results. As we know from the later history of the Caecilian movement in Hungary, Bogisich’ reform conception, which was well beyond his age, only found followers much later, among the Cecilian generation of the 1930s. In spite of the fact, that the parish priest of Buda Castle’s Matthias Church he had already found the way towards a possible renewal of Hungarian Catholic church music in the last decades of the 19th century.

Curated by Marietta Bukáné Kaskötő